Gideon Weissman

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

A look back at Frontier Group's research on consumer complaints about predatory banks, lenders and other financial companies, and our work defending the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau from attempts to weaken or dismantle it.

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

In the years leading up to the 2008 financial collapse, millions of American homeowners were lured into mortgages whose terms they could not understand and which they had little hope of ever being able to repay. Easy credit inflated the housing bubble, and when the bubble popped the resulting collapse brought down the fortunes of millions of families as well as the broader economy.

This chain of events led directly to creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform legislation.

Originally dreamed up by Elizabeth Warren, and made real due in no small part to the advocacy and organizing efforts of our friends at U.S.PIRG, the CFPB represented a revolutionary step forward for consumers. For the first time, the public could rely on a federal agency with the sole mission of protecting them in the financial marketplace — not just from predatory mortgage companies, but also from unscrupulous or careless banks, debt collectors, credit agencies and more. In other words, the CFPB was envisioned as a cop on the beat to make sure these companies didn’t break the law or abuse their customers. The CFPB was also given the power to make new rules to keep consumers safe, and was tasked with providing resources for public financial education.

The creation of the CFPB was an important public interest victory. But a key sidelight was the unique opportunity the new agency created for researchers to better understand the threats that consumers face in the financial marketplace, and use that information to educate consumers and policymakers.

As written in Dodd-Frank, the CFPB was made responsible for “collecting, investigating, and responding to consumer complaints.” This directive led to the creation of a national system for collecting and responding to consumers dealing with misbehaving or unresponsive companies.

As we described it, the resulting complaint system created a two-way flow of information that was a model of “effectiveness and responsiveness”: Consumers could register complaints with the federal government, which would then forward those complaints to the responsible company and keep track of the company’s response. Companies knew that the CFPB was keeping tabs on complaints and taking action, particularly when response to complaints was lackluster or there were repeated allegations of illegal or abusive behavior.

Government systems for receiving and addressing consumer complaints were nothing new. What was new was that the CFPB opted to make an anonymized version of the database available to the public – providing regularly updated data on the companies, practices and financial products that were harming consumers.

In March 2012, the CFPB opened the Consumer Complaint Database, a vast trove of data about the threats and mistreatment consumers faced in the financial marketplace. As researchers, we saw an opportunity to use this data to educate the public. In September 2013, we published Big Banks, Big Complaints: CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database Gets Real Results for Consumers, written by Tony Dutzik and Spencer Alt of Frontier Group, and Ed Mierzwinski, Laura Murray and Ashleigh Giliberto of the U.S. PIRG Education Fund. For the report, we sliced and diced nearly 19,000 complaints about banks.

Our research shed new light on a basic fact that many consumers had long known: your bank might actually be ripping you off. We described how “banks have often taken advantage of consumers through excessive fees, hidden charges, and other abusive practices.” We found that problems with checking accounts accounted for more than three quarters of bank complaints, and that twenty-five U.S. banks accounted for more than 90 percent of all complaints to the CFPB. Wells Fargo was the most complained-about bank, while TCF National Bank had more complaints per billion dollars in deposits than any other bank. (Not long thereafter, the CFPB caught Wells Fargo scamming its customers with expensive fake accounts, ultimately leading to a $3 billion fine; and soon after that the CFPB discovered TCF National Bank was tricking its customers into signing up for costly overdraft services.)

This report — and those that soon followed with analyses of complaints about credit bureaus, debt collectors, student loans, and more — were covered in outlets like the New York Times and the Washington Post, each report and new story not only helping consumers protect themselves, but also giving them a better understanding of the resources available to them through the CFPB.

Each complaint analysis also looked at ways that the CFPB could improve its operations to better carry out its mission. For example, our 2013 report proposed that the CFPB start publishing the actual text of consumer complaints, to make public more of the flavor of consumers’ experiences and allow researchers to more easily discern patterns of behavior by financial actors. Just two years later, the CFPB began publishing consumer complaint narratives (scrubbed of personal information, of course). In the following years these narratives became important tools for understanding consumers’ experiences. Complaint narratives allowed us to add context to problems like medical debt collection, or the financial challenges facing military servicemembers.

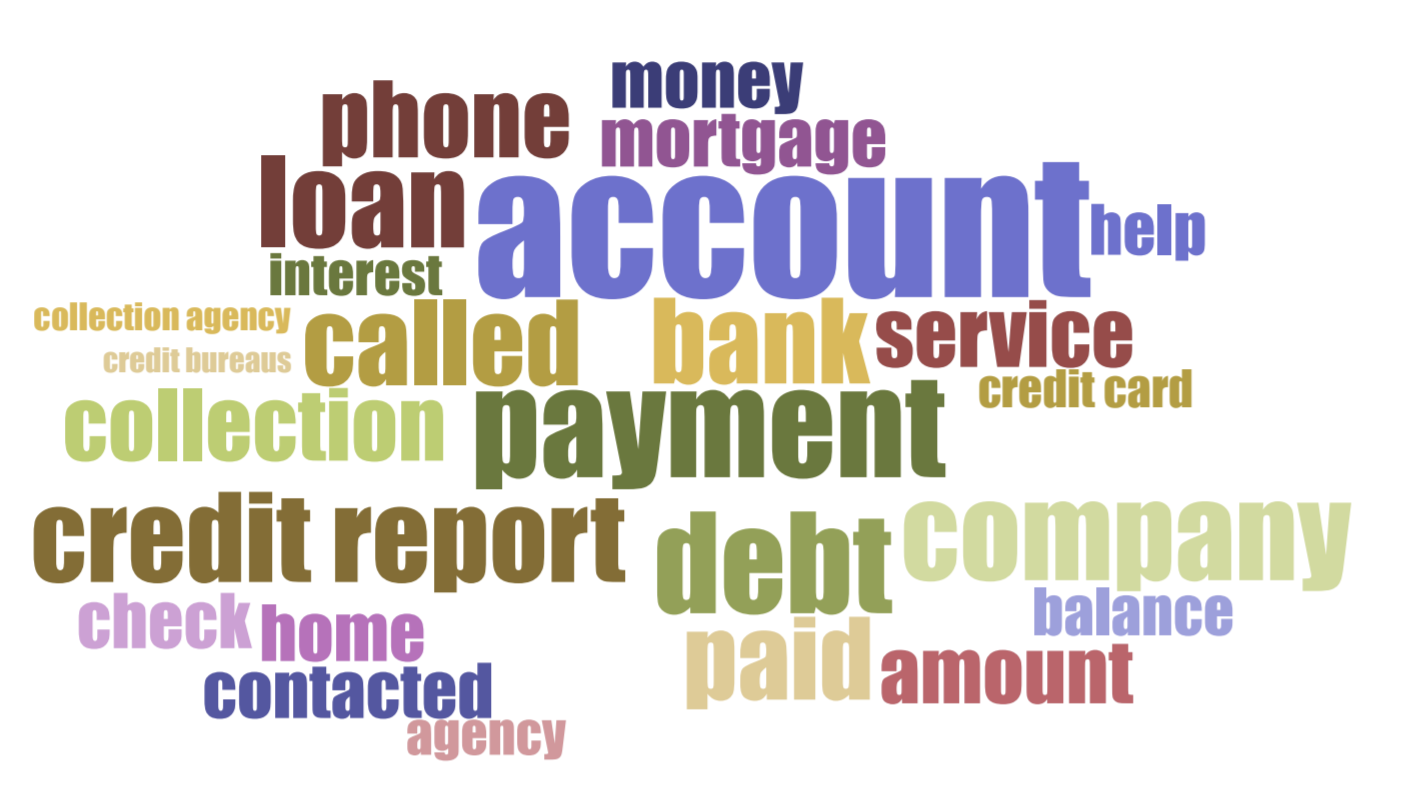

Word cloud of consumer complaint narratives from our 2017 report analyzing military servicemember complaints

From the moment of its creation the CFPB routinely came under heavy attack from financial companies that preferred a return to the Wild West days of pre-2008. So one function of our reports was to demonstrate how necessary and useful this agency actually was.

The arrival of the Trump administration in 2016 made that function critical. To defend the agency against an administration hostile to its mission, we published a steady stream of new reports highlighting the CFPB’s role in protecting consumers, with the dual aim of uncovering consumer problems and educating the public that their new cop on the beat was at risk of being dismantled.

We also conducted research and provided information to respond to specific attacks on the CFPB’s ability to protect consumers. In 2018, for example, CFPB then-Acting Director Mick Mulvaney was considering blocking access to consumer complaint data. In response, we released the whitepaper Shining a Light on Consumer Problems with U.S. PIRG. The paper documented how a public database made the financial marketplace safer and fairer; helped consumers to research individual problems; held companies accountable and helped them to improve their customer service; and enabled researchers like us to keep an independent eye on consumer problems and on the CFPB itself.

Under the Trump administration, the CFPB dramatically scaled back its consumer protection efforts. But our work was part of a broader campaign to protect some of the bureau’s key functions, including its continued operation of a public complaint database. The public supported the effort; in 2017, the New York Times wrote that the CFPB “may be too popular” for its opponents to sideline.

Our consumer complaint research gained new urgency in 2020 with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought a level of economic disruption and uncertainty not seen since 2008. Millions faced a sudden loss of income, and as consumers burned through their savings they faced new vulnerability from everything from payday loans to overdraft fees to debt collection. Federal legislation like the CARES Act helped, but also created new sources of confusion, with sometimes complex eligibility criteria for relief, and inconsistent rule-following by financial companies.

We turned to the Consumer Complaint Database for insight. We published new research on mortgage servicers, finding that — just as in the Great Recession — people were having real trouble getting the relief they needed. With U.S. PIRG, we showed that complaints were surging to new heights, in particular complaints about bad information on credit reports. This research was covered in outlets like USA Today and CNBC, and we shared our insights directly with congressional and CFPB staff. We also published a guide and a new digital tool to help members of the public conduct their own research into consumer complaints.

Today, 13 years after the 2008 financial collapse and almost exactly a decade since the CFPB first opened its doors, we’ve completed a dozen research reports on consumer complaints, providing consumers with useful information while demonstrating the need for an effective watchdog to protect consumers in the financial marketplace. And the need for this kind of oversight isn’t going away. Each year consumers are confronted with new and potentially risky financial products like cryptocurrencies and digital wallets (both of which are the source of growing numbers of complaints), while financial companies continue to devise devious new tricks and traps for their customers. By continuing our efforts to shine a light on problems and abuses we hope to help consumers navigate this changing marketplace — while also supporting the evolving policy and diligent enforcement that it will take to keep our families and our livelihoods safe.

Photo by Jake Allen on Unsplash

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group