Bryn Huxley-Reicher

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Proposed or approved oil and gas wells, gas pipelines and LNG terminals could significantly increase climate emissions at a time when rapid cuts are needed.

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

There’s a lot of excitement around clean energy in the U.S. – especially after the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. But we can’t fight global warming without cutting our use of fossil fuels. At the recent climate change-focused Conference of the Parties 27, the world failed to make a clear commitment to phase out fossil fuels. And in the U.S., the fossil fuel industry is pushing a massive expansion intended to keep the nation – and the world – hooked on dirty fossil fuels indefinitely.

My colleague Tony Dutzik has shown that there are more fossil fuel-related projects under federal environmental review than there are clean energy projects, and that building new fossil fuel infrastructure can lock in demand for those fuels and the climate and health damage they do for decades.

But just how big are the fossil fuel industry’s plans for expansion? And how much pollution could result from those projects? A few recent analyses provide some clues:

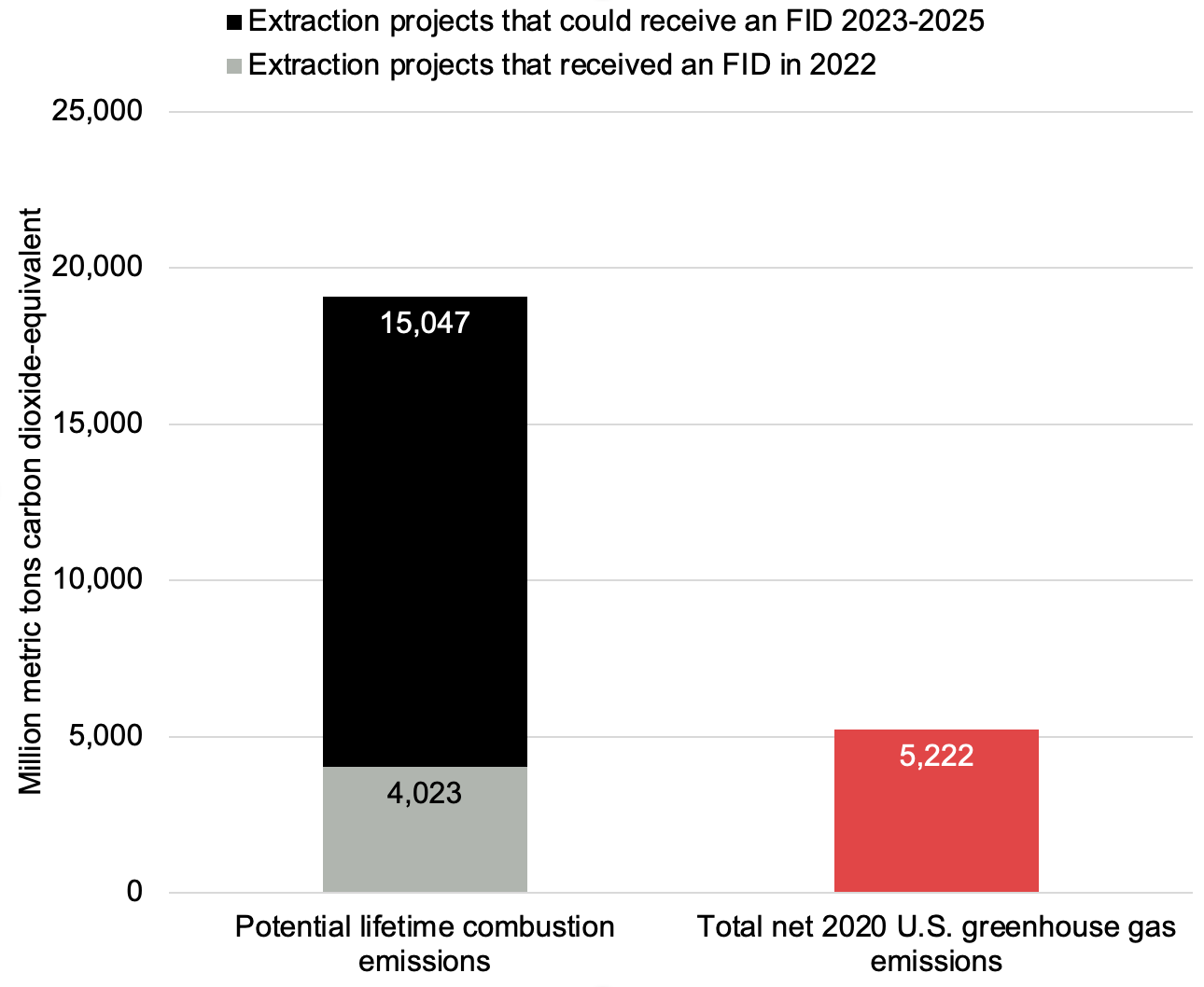

An analysis by Oil Change International of proposed oil and gas fields and coal mines found that the U.S. approved far and away the largest expansion of oil and gas extraction of any country in 2022. Projects that received a final investment decision (FID) in 2022 are projected to release 4 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) over their lifetimes if their fossil fuel reserves are fully exploited and burned – the equivalent of more than 75% of the total net 2020 greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. The biggest expansion of fossil fuel production in the U.S. is expected in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico, followed by the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and neighboring states.

And there are potentially even bigger extraction projects in the pipeline. Oil Change International’s analysis found that the U.S. also has by far the largest projected emissions from proposed projects that could be finalized between 2023-2025, with anticipated lifetime emissions from those projects of approximately 15 billion metric tons of CO2 – the equivalent of almost three times total net 2020 U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Figure 1. Potential lifetime combustion emissions from future oil and gas extraction projects vs. U.S. net greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 (Data: Oil Change International)[1]

Photo by Bryn Huxley-Reicher | TPIN

Incredibly, these estimates only account for emissions of CO2 from burning the fossil fuels, and not emissions of methane or other non-CO2 greenhouse gases, or emissions from extraction, processing and transport, meaning they likely significantly undercount potential damage. The fossil fuels produced by those projects will drive further climate damage, air pollution and threats to health and safety.

Pipeline projects could also lead to significant increases in carbon pollution. On its own, for example, the Mountain Valley Pipeline and Equitrans Expansion project – which has been in the news as the centerpiece of Senator Joe Manchin’s bill to change energy project permitting – would release 1.6 million metric tons CO2-equivalent during construction alone, while operation of the pipeline and burning the gas it carries could cause annual emissions of up to about 48 million metric tons CO2-equivalent.[2] The potential annual emissions are equivalent to the annual emissions from nearly 13 average coal-fired power plants.

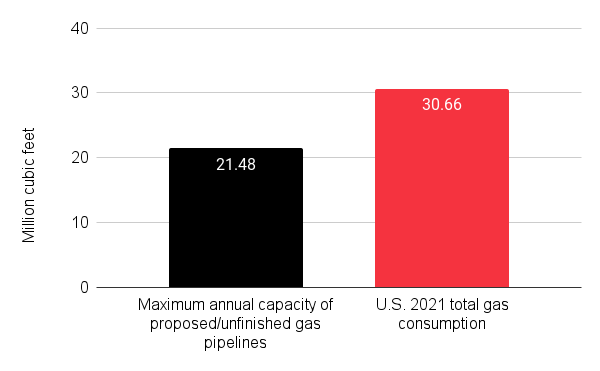

The Mountain Valley Pipeline project is far from the only major pipeline project proposed in the U.S. According to data obtained from Oil and Gas Watch, the maximum total capacity of the 61 new gas pipelines or pipeline expansions that have been announced or which have not yet finished construction is equivalent to about 70% of the gas the U.S. consumed in 2021.

These maximum capacities are just that: potential maxima, not what will necessarily be carried if these pipelines are built and run. The pipelines may not operate at full capacity, some of the gas they transport may supplant gas in other pipelines or be used to replace other carbon-emitting fuels, and some of the expanded pipelines may link to one another and the capacity additions may not be additive. So the increase in net capacity is likely lower – and perhaps much lower – than the value above. But at a time when the science is clear that we need to be reducing greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel use quickly, any net increase in capacity (and the pollution that comes with burning that fuel) is going in the wrong direction.

Figure 2. Maximum annual capacity of announced and unfinished methane gas pipelines vs. total U.S. 2021 gas consumption

Photo by Bryn Huxley-Reicher | TPIN

A recent analysis by the Environmental Integrity Project found that 24 liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals proposed or under construction in the U.S. could emit the equivalent of 90 million metric tons of CO2 per year, more than all the cars and trucks in Florida or New York State. Those emissions are just from the operations of the terminals themselves and don’t count the emissions from extracting or burning the gas they handle. These 24 terminals could produce at least 310.62 million metric tons of LNG per year, about three times America’s current LNG export capacity of 104.5 million metric tons.

Continued investment in and expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure is a mistake, and one that we all pay the price of in the form of air pollution that harms our health and damages the climate, as well as risks to safety. That’s a price we can’t afford.

—

[1] Oil Change International, Investing in Disaster: Recent and Anticipated Final Investment Decisions for New Oil and Gas Production Beyond the 1.5°C Limit, November 2022, p. 20, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20221207094523/https://priceofoil.org/content/uploads/2022/11/Investing_In_Disaster.pdf; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, 14 April 2022, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20221229101017/https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks.

[2] Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Mountain Valley Project and Equitrans Expansion Project: Final Environmental Impact Statement, June 2017, pp. 4-502, 4-503, 4-504, 4-505, 4-619 and 4-620, accessed at https://cms.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/Final-Environmental-Impact-Statement_1.pdf. Construction emissions total includes direct emissions from construction and emissions from deforestation during construction. Annual emissions total includes the carbon content of the pipelines’ gas capacity and the ongoing emissions from deforestation associated with the project.