Fossil fuels outnumber clean energy projects in NEPA environmental review

Renewable energy is on the rise across America. But there are still lots of pipelines and other fossil fuel projects awaiting federal environmental review.

With the midterm elections now in the rearview mirror, some version of Sen. Joe Manchin’s “permitting reform” legislation could soon be coming back to life.

Proposed as part of the deal that led to passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in August, the legislation would have expanded the federal government’s power to build electric transmission lines, approved the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline, and closed off various avenues for objections under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Sen. Manchin withdrew the proposal from spending legislation in September, but it could be attached to a must-pass defense spending bill during the lame duck session of Congress.

Advocates for “streamlining” environmental review argue that, with renewable energy on the rise and the nation needing to dramatically ramp up its production of clean energy to meet its climate goals, traditional forms of environmental review could slow America’s transition away from fossil fuels. These arguments often cite some version of the following factoid, with this example from a Washington Post editorial:

“An analysis last year found that of the projects undergoing NEPA review at the Department of Energy, 42% concerned clean energy, transmission or environmental protection, while just 15% were related to fossil fuels.”

This factoid, produced by the R Street Institute (and a similar one, also sourced to R Street, that two-thirds of the energy projects listed on the federal permitting dashboard are renewable energy projects) has been used to create the impression that the majority of energy-related projects currently subject to federal environmental review are clean energy projects.

This is not true.

The data sources used by R Street capture only a small slice of the energy-related projects subject to federal environmental review. A more complete assessment finds that the number of fossil fuel-related projects in NEPA review likely significantly exceeds the number of clean energy projects.

Missing the pipelines for the trees

The two sources cited by R Street – the federal permitting dashboard and the U.S. Department of Energy’s NEPA Policy and Compliance website – both exclude many fossil fuel projects.

The federal permitting dashboard was created to track projects – mostly transportation projects – eligible for streamlined permitting under the 2015 Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. It includes information on a small number of so-called “other projects,” but is far from a comprehensive list of energy projects facing environmental review. As of late October, the dashboard showed only two fossil fuel projects – both related to liquefied natural gas (LNG) – for which the project status was listed as “in progress” or “planned.” That’s compared to 20 renewable energy projects (16 for offshore wind) and six transmission projects.

Similarly, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) website for tracking Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments includes only a small share of the energy-related projects facing environmental review. As of late October 2022, the DOE site included three active LNG projects requiring environmental impact statements (EIS) and one requiring an environmental assessment (EA, a less-comprehensive form of environmental review that can lead either to a finding of no significant impact or requirement for further study), as well as two EISs related to the now-terminated Keystone XL pipeline, for a total of six fossil fuel-related projects. The DOE site also included seven active electric transmission projects with EISs or EAs, as well as one hydropower project and two wind projects, for a total of 10 projects that could arguably be considered “clean energy” or transmission projects.

Looking at those two sources would give the impression that the majority of energy projects in environmental review are renewable energy or transmission projects. But that is not the case. The key agencies responsible for gas pipelines and for oil and gas production on public lands (among other fossil fuel-related projects) do not consistently report to either the federal dashboard or the DOE tracker. A review of those agencies’ NEPA websites reveals a large number of fossil fuel projects currently requiring environmental review.

Oil and gas drilling on public lands and pipeline projects fill review dockets

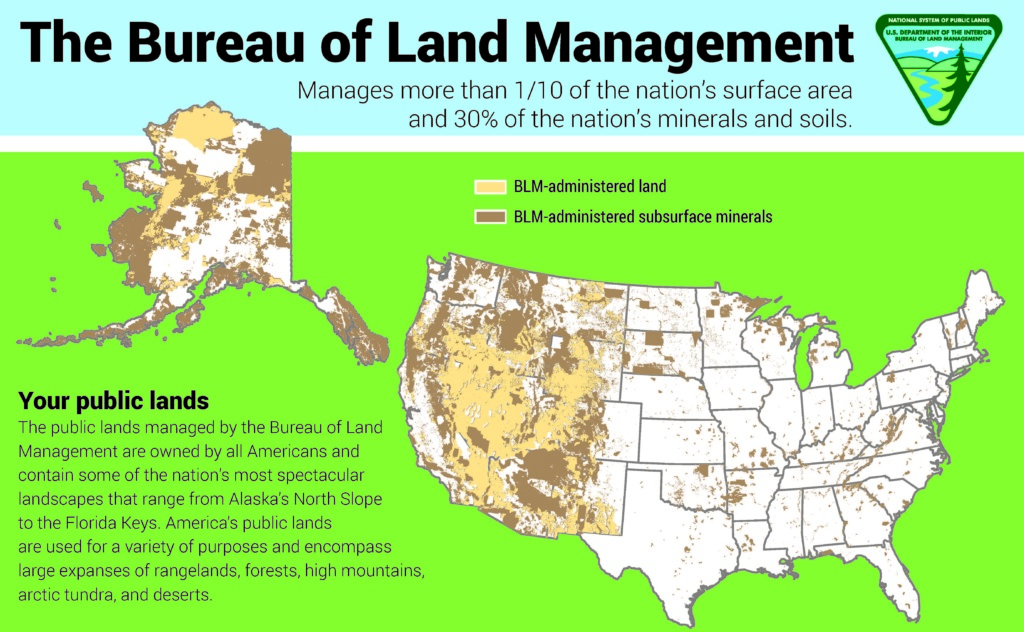

The federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages 245 million acres of surface land in the United States – one-tenth of the nation’s surface area – and 700 million acres of subsurface rights. As a federal agency, decisions related to that land and those minerals are subject to NEPA.

The Bureau of Land Management manages a lot of land. And minerals. Its decisions are subject to environmental review under NEPAPhoto by Bureau of Land Management | Public Domain

We reviewed the BLM’s National NEPA Register for active projects classified as “fluid minerals” and “renewable energy” projects for 2022 and 2023 requiring an EIS or EA. There were 95 “fluid minerals” – that is, oil and gas – projects in the register, compared with only 11 renewable energy projects, a ratio of dirty to clean projects of more than 8-to-1.

The renewable energy projects were more likely than not to require the more comprehensive EIS, whereas the fossil fuel projects required EAs. Given their impacts on the climate and public health, fossil fuel projects likely require more stringent environmental review than they currently receive, but nevertheless, the overall “pipeline” of fossil fuel projects on BLM land requiring environmental review is far greater than that of clean energy projects.

Another federal agency, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), is responsible for regulating gas pipelines and infrastructure and hydroelectric projects. We reviewed FERC environmental filings for 2022, finding that 28 gas-related projects and 20 hydro-related projects (many of them license renewals for existing hydroelectric dams, rather than new-build hydro projects) were subject to environmental review in the form of an EIS or EA. [1] Unlike the projects under the jurisdiction of the BLM, numerous large gas pipeline projects have required EISs, whereas the vast bulk of hydro projects required less-rigorous EAs.

Together, the fossil fuel-related projects under the jurisdiction of those two agencies clearly outnumber the clean energy projects. But the lack of consistent data on environmental review makes a comprehensive, apples-to-apples comparison of the types of projects subject to NEPA review impossible. A 2014 Government Accountability Office report, for example, noted that “Governmentwide data on the number and type of most NEPA analyses are not readily available, as data collection efforts vary by agency.”

There is, however, one source of data that provides a picture of environmental review across federal agencies.

Fossil fuel projects have dominated recent published EISs

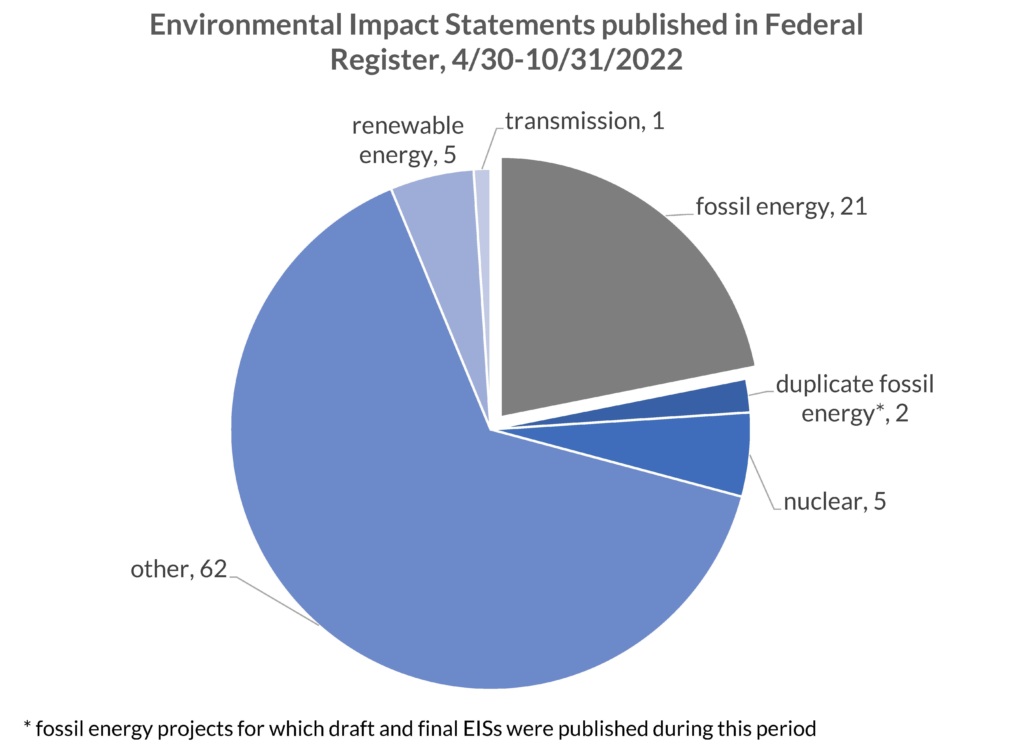

The EPA maintains a tracking system for EISs published to the Federal Register. This source has its limitations – excluding projects that have not reached at least the stage of a draft EIS, as well as projects receiving lower levels of environmental review, such as EAs.

We reviewed this database for EISs published between April 30 and October 31, 2022 – a six-month period – during which 96 draft, final or supplemental EISs were published to the Federal Register. Of those, at least 21 EISs were related to unique oil and gas projects, most of them pipelines. [2] By comparison, only five renewable energy projects had EISs published in the Federal Register during this time, along with five projects related to nuclear energy production and one transmission project. Depending on whether one’s definition of “clean energy” includes nuclear power, the ratio of fossil fuel to clean energy projects in the EPA tracker is either roughly two-to-one or roughly four-to-one.

Source: EPAPhoto by Frontier Group | TPIN

What does all this tell us?

Factoids based on incomplete data on the number and kinds of projects subject to NEPA review have been used to minimize the perceived danger that “permitting reform” will lower the level of public scrutiny and engagement related to fossil fuel projects. Our analysis shows that there are numerous fossil fuel projects currently in NEPA review and that the sheer number of those dirty energy projects likely significantly exceeds the number of clean energy projects.

Comparing the number of projects in environmental review queues, however, doesn’t tell us much that’s worth knowing, either about the trajectory of America’s energy system or the role of environmental review in speeding up or inhibiting the transition to a clean energy economy.

Comparing the number of projects doesn’t tell us anything about the kinds of projects involved – their size or their potential impacts on the environment or the climate. A single pipeline project in Louisiana for which a Final Environmental Impact Statement was published in 2022, for example, was found to be capable of carrying enough methane gas to produce 102 million tons per year of greenhouse gases (CO2 equivalent) if all the gas were burned – increasing *total* U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by about 2 percent. [3] Comparing the approval of major, long-lived fossil infrastructure projects with, say, license extensions for hydroelectric plants risks comparing grapes with watermelons.

Comparing the number of projects also doesn’t tell us much about the type or duration of review to which the projects are subject. And it doesn’t tell us about projects that are not subject to thorough environmental review (such as the hundreds of BLM fossil energy projects issued “categorical exclusions” under NEPA) but should be.

Lastly, it doesn’t tell us much about agencies’ success or lack of it in moving projects through the environmental review process and/or using that process to drive better, less environmentally disruptive projects. While media coverage often focuses on delays to high-profile projects, key agencies continue to make progress in permitting clean energy projects. In fiscal year 2021, for example, the BLM approved projects supporting the addition of nearly 2.9 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity on public lands, and the agency estimates that it will permit nearly 32 gigawatts of renewable energy projects by the end of fiscal year 2025, enough to power more than 9 million homes.

The current debate over environmental review is important and timely. In some cases, environmental review may slow the pace of beneficial projects, while in other cases, current systems of environmental review may fail to subject damaging projects to necessary public scrutiny. With the nation’s climate goals hanging in the balance, and with communities around the country already burdened by pollution and disruption from fossil fuel development, targeted improvements to the system could deliver benefits, as opposed to the broadscale weakening proposed in the Manchin bill.

Getting to that kind of a result requires good information. The fossil fuel industry is not dead, its products continue to pollute our air and harm the climate, and fossil fuel production wells, pipelines and processing facilities still damage our environment and our health. Environmental review is essential to alert the public to potential harms from those projects and hold the fossil fuel industry accountable to protecting the public.

With any luck, there will soon be a day when the only major energy projects being proposed in the United States are clean energy projects. The data, however, are clear: That day has not yet arrived.

Notes:

[1] Excluding projects that consist solely of abandonment of existing pipeline infrastructure.

[2] Excludes two EISs for projects that had draft and final EISs filed during this period to avoid double-counting. Excludes EIS for oil and gas decommissioning activities off the Pacific coast.

[3] Final Environmental Impact Statement at page 4-125.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Lisa Frank

Executive Director, Washington Legislative Office, Environment America; Vice President and D.C. Director, The Public Interest Network

Lisa directs strategy and staff for Environment America's federal campaigns. She also oversees The Public Interest Network's Washington, D.C., office and operations. She has won millions of dollars in investments in walking, biking and transit, and has helped develop strategic campaigns to protect America's oceans, forests and public lands from drilling, logging and road-building. Lisa is an Oregonian transplant in Washington, D.C., where she loves hiking, running, biking, and cooking for friends and family.

Find Out More

How to get more from state energy efficiency programs

“Certified natural gas” is not a source of clean energy

Energy Efficiency for Everyone