Building fossil fuel infrastructure locks us into a higher-carbon future

What's at stake in "permitting reform"

Fossil fuel infrastructure harms our environment and health today. And adding more of it makes the job of breaking free from fossil fuels in the future that much harder.

Despite the recent rise in renewable energy, fossil fuel projects continue to dominate the list of projects requiring federal environmental review.

But if the arc of the technological universe is bending toward cleaner energy technologies such as wind and solar, should we still be concerned about fossil fuel infrastructure projects like the Mountain Valley Pipeline (which would have been fast-tracked under Sen. Joe Manchin’s permitting bill)? After all, if we have faith in the clean energy transition, wouldn’t it be a worthwhile trade-off to allow for the construction of some soon-to-be-obsolete fossil fuel infrastructure now in order to also unlock a wave of new clean energy?

Among those making that argument was Eric Levitz in a recent piece in the New Yorker’s Intelligencer. Levitz writes:

If public policy can make carbon-free energy as cheap and broadly accessible as oil, fossil-fuel assets will be stranded. Contrary to the presumptions of a climate strategy that prioritizes “keeping it in the ground,” fossil-fuel infrastructure does not induce its own demand.

Is this right? Are the companies proposing to continue the large-scale build-out of gas infrastructure in the U.S. idiots, pushing forward with multi-million dollar investments doomed to be abandoned in no time flat? Or, will the continued build-out of fossil fuel infrastructure make it harder for us to kick oil and gas by “inducing its own demand”?

The answer to the first question is “no” – companies proposing gas expansion fully intend to maximize their use of that infrastructure for decades to come, and there is reason to think – especially given the stranglehold that the fossil fuel industry has over public policy and America’s history of inconsistent (at best) commitment to climate action – that they’ll be able to get their wish.

The answer to the second question is “yes.” Fossil fuel infrastructure absolutely induces its own demand.

To understand why, we need to talk about “carbon lock-in.”

What does carbon lock-in mean?

The idea of carbon lock-in is pretty simple: Every expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure deepens our dependence on those fuels and creates a variety of additional headwinds to change.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into the theory and rationale behind carbon lock-in, this paper does a thorough and fairly accessible job of explaining the concept.

But we think it’s better to illustrate with an example.

Carbon lock-in: An example

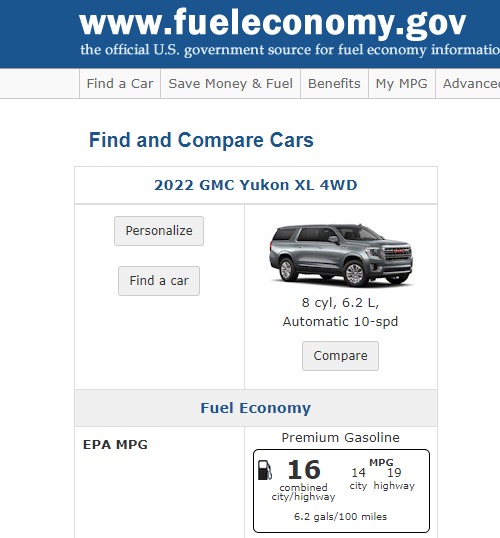

Let’s say you go out and buy a brand new GMC Yukon XL – which gets a whopping 16 miles per gallon of gasoline. Now, let’s say that a year later, you have an environmental epiphany and replace the Yukon with a small EV or even an e-bike. Hooray for you!

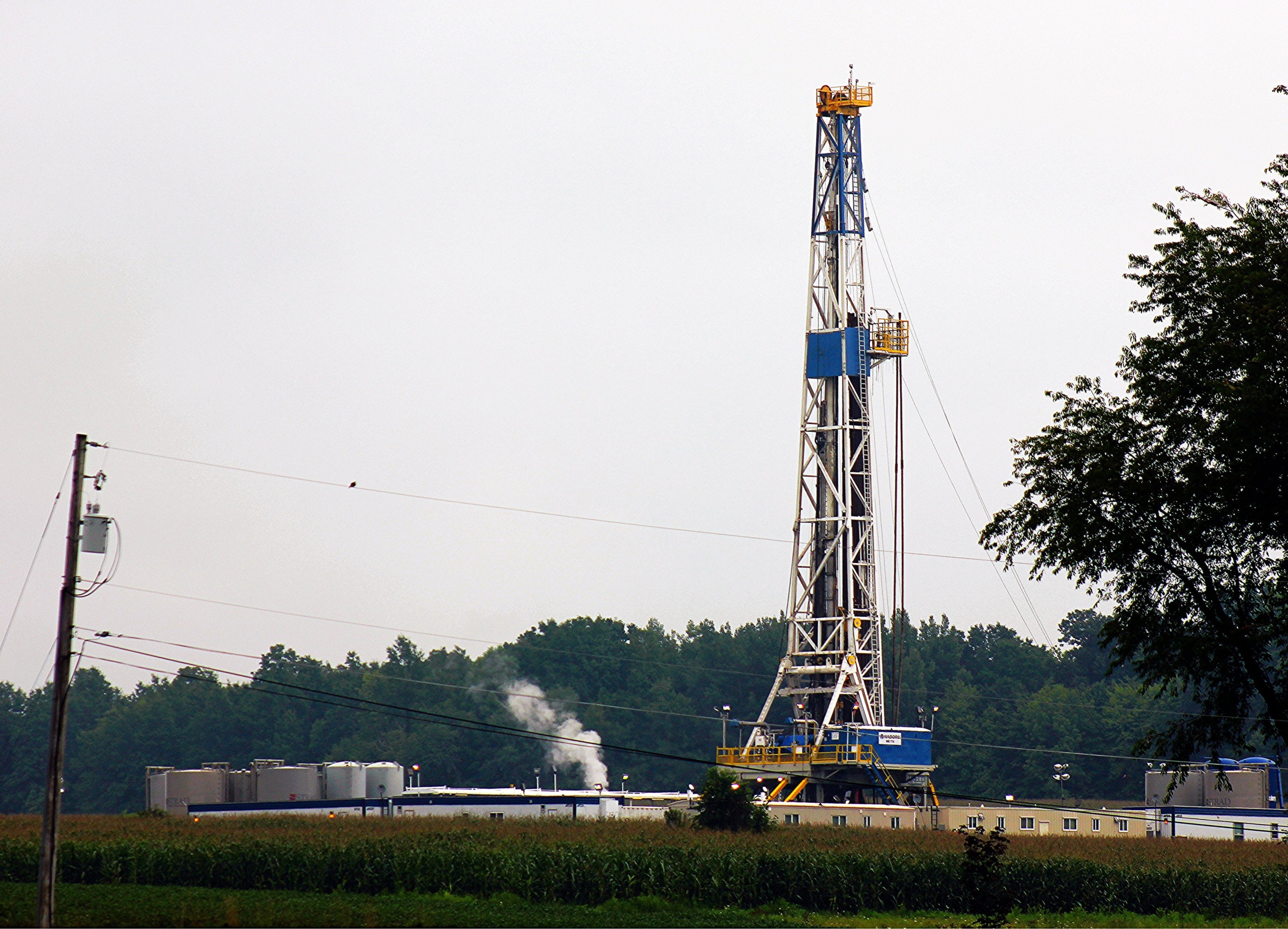

Not a great choice for the environment. And one with long-lasting implications.Photo by U.S. EPA | Public Domain

But what happens to the Yukon?

Unless you are prepared to eat a huge investment and send it straight to the scrapyard – to “strand” the asset – you are going to sell it to someone else. And that someone else will drive it for a while and eventually sell it to someone else until the Yukon has either lived its god-given life of 150,000 miles or has become more expensive to operate than it’s worth.

In other words, all other things being equal, GM’s decision to build – and your decision to buy – a gas-guzzling vehicle has committed the world to a lifetime’s worth of emissions from that vehicle. That’s carbon lock-in.

Now, let’s imagine that, in five years, EVs become cheaper to buy and fuel than internal combustion vehicles. That’s good! But it doesn’t necessarily mean that the Yukon is going to be retired any earlier than it otherwise would. Because for that to happen, EVs would not only need to become cheaper than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, they’d need to become radically cheaper. In short, it would need to become cheaper to both buy and operate a new EV than to simply operate the already-existing Yukon.

That could happen. And, to switch frames a minute, it’s starting to happen with renewable energy sources competing with fossil fuel power plants. But it’s a very, very high bar to meet.

And even then, there’s still no guarantee that the Yukon will be retired. Let’s imagine someone invents a business model that pays people to park their old ICE vehicles in their driveways and keep the engine running to power computers carrying out mathematical calculations. Absurd, right? For fun, let’s give that business model a name. Let’s call it “schmyptocurrency.”

Now you have a bunch of clean EVs traversing the roads … AND a bunch of dirty old SUVs repurposed to mine schmypto. You haven’t retired them, you’ve just downcycled them. And emissions don’t decline as quickly as needed, if they do at all. This is, in fact, what’s happening with retired fossil fuel power plants that are now being resurrected to mine crypto.

Getting rid of fossil fuel infrastructure isn’t easy

Let’s say you want to change that situation and make sure the Yukon is sent to an early grave. How would you do it?

One way you could do it would be to hike the gas tax or ban ICE vehicles or SUVs altogether. Those “sticks” would reduce the value of the Yukon and likely result in earlier retirement. But they would likely be strenuously opposed by Yukon owners – who are now one person more numerous (and, therefore, more politically powerful) than they would otherwise be thanks to your decision to buy the Yukon in the first place.

And not only might the Yukon owners fight like hell against those measures, they might even turn the tables and use their political clout to subsidize their dirty existing vehicles (as states like Wyoming are doing to keep their existing coal plants running in the face of competition from cheaper renewables). Or they might try to limit the spread of cleaner technologies that might compete with and devalue their investment (as utilities have done for more than a decade to prevent individuals from adopting rooftop solar).

Does any of that make sense for society or the economy? No. Does special interest pressure often result in suboptimal outcomes – particularly in energy policy? You bet it does.

The other option for policy makers is to buy off the Yukon owners. This is pretty much what the U.S. did during the Cash for Clunkers program under Obama. It works … sorta. But it’s expensive. It consumes resources that could be used for other things. And every additional Yukon allowed on the road now is one more that taxpayers will eventually have to pay to retire somewhere down the line.

How can we avoid shackling ourselves to fossil fuels?

In sum, fossil fuel infrastructure, once built, creates inertia that distorts future decision-making over the lifetime of the asset – 12-15 years in the case of a car, decades more in the case of a pipeline. The addition of that new fossil fuel infrastructure absolutely induces future demand. And, absent radical technological shifts or strong government policy – or both – that infrastructure won’t just “strand itself.”

Clean energy advocates have long understood this. Which is why many of us pushed for massive early deployment of wind, solar, energy efficiency, electric vehicles and the like in the hopes of creating *positive* path dependencies to counter the carbon lock-in established by previous generations of fossil fuel investment.

Further entrenching and accelerating the deployment of energy efficiency, renewables, energy storage, low-emission modes of transportation, etc. remains critical. Smart reforms to the ways that clean energy is financed, planned and permitted can accelerate those “good” path dependencies.

But let’s not pretend for a second that expanding fossil fuel infrastructure doesn’t do the same thing in reverse. Indeed, the paper cited above lays out the logic:

[F]ossil fuel–supporting infrastructures such as pipelines, refineries, and gasoline stations also contribute to locking in carbon intensity insofar as their value is dependent on the extraction and transport of fossil fuels. … Thus, owners of assets that do not directly burn fossil fuels may nonetheless have strong incentives to favor policies that maintain lock-in insofar as their assets are specific to the technologies favored by the existing form of lock-in. Such supporting infrastructure also suggests the self-reinforcing incentives to resist change.

Environmental review (thanks, NEPA!) enables us to get a sense of what the stakes might be in moving forward with new fossil fuel infrastructure – and they are high. Just one proposed pipeline project in Louisiana, for example, would carry enough gas to increase total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by about 2%. That is not something that we can safely ignore.

Building a new pipeline increases the chances that someone, somewhere in the country will be burning methane gas in 5, 10 or 20 years who otherwise wouldn’t – even if we succeed in making cleaner alternatives cheaper and better in the meantime.

The science is clear that additional development of oil and gas resources is inconsistent with preventing the worst impacts of global warming. That doesn’t mean that trade-offs and compromises won’t be necessary along the way to continue the march of progress toward a clean energy future. But we cannot afford to pretend that those trade-offs simply don’t exist.

Fossil fuel infrastructure does induce its own demand. And allowing more of it creates impacts that are consequential. It creates real harm for communities bearing the immediate brunt of fossil fuel production today. And it creates an even bigger challenge for our future selves as we struggle to undo an even bigger pile of historical mistakes.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Johanna Neumann

Senior Director, Campaign for 100% Renewable Energy, Environment America

Johanna directs strategy and staff for Environment America's energy campaigns at the local, state and national level. In her prior positions, she led the campaign to ban smoking in all Maryland workplaces, helped stop the construction of a new nuclear reactor on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay and helped build the support necessary to pass the EmPOWER Maryland Act, which set a goal of reducing the state’s per capita electricity use by 15 percent. She also currently serves on the board of Community Action Works. Johanna lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with her family, where she enjoys growing dahlias, biking and the occasional game of goaltimate.

Matt Casale

Former Director, Environment Campaigns, PIRG

Find Out More

How to get more from state energy efficiency programs

“Certified natural gas” is not a source of clean energy

Energy Efficiency for Everyone