Improving Price Transparency

Oregon Patients and Providers Need Better Information on the Cost of Health Care

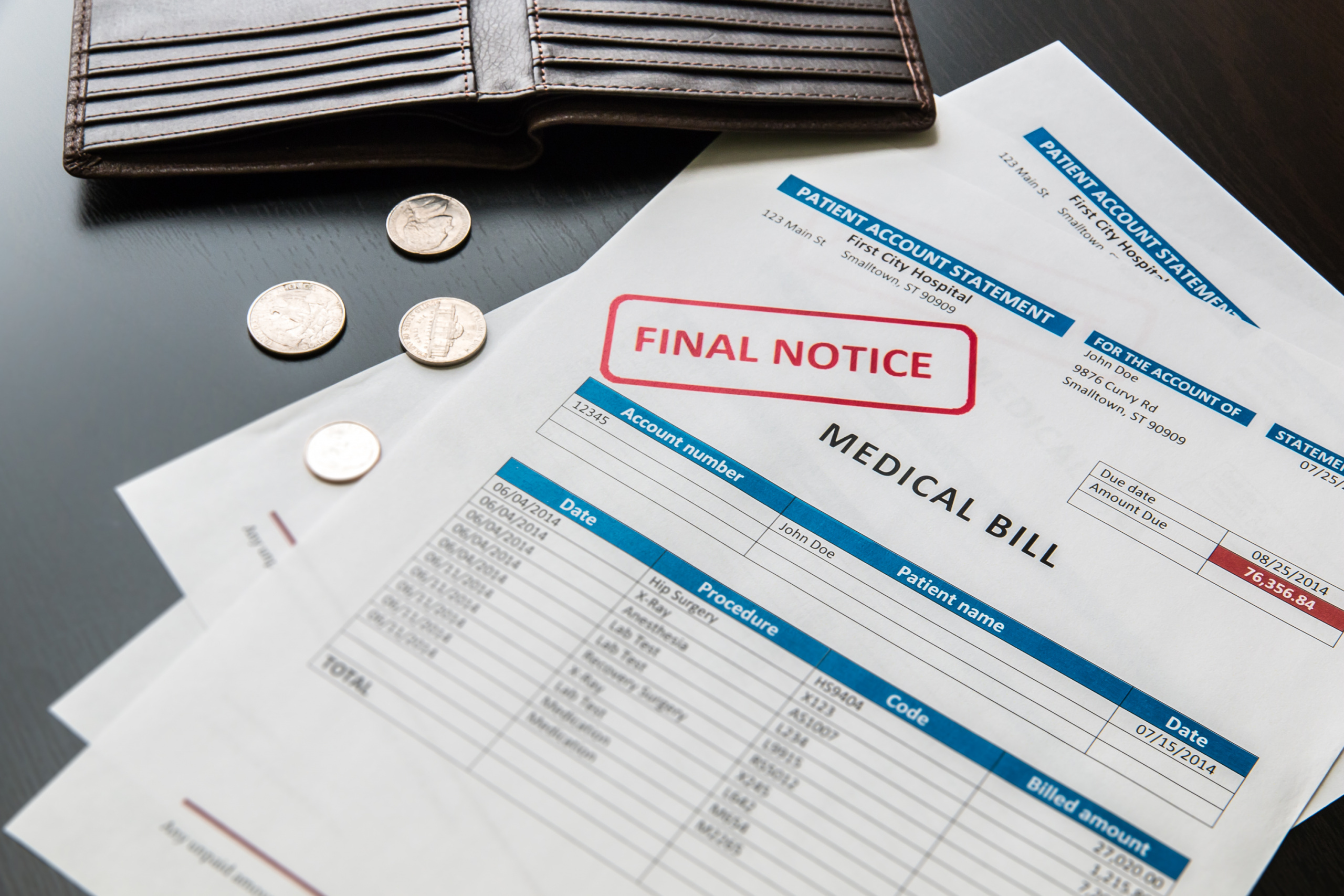

Oregon consumers have a limited ability to learn the price of health care in advance of receiving treatment. When patients are asked to make decisions about care without access to meaningful price information, they are unable to make informed decisions. Oregon should pursue additional measures to improve the visibility of prices for patients, providers and health plans.

Downloads

Health care spending in Oregon averages more than $8,000 annually per person, and increased 60 percent from 2004 to 2014 (before adjusting for inflation).[1] Much of this spending occurs without patients or providers knowing the price of care in advance.

Opaque and unavailable prices for health care services violate the basic consumer right to know in advance about the price of goods or services. When consumers are asked to make decisions about care without access to meaningful price information, they are unable to make informed decisions in high-stakes situations that can profoundly affect their future health and financial security.

Improving the price transparency of health care services isn’t just about fulfilling a basic consumer right – it is also a critical step in diagnosing and addressing the high cost of health care. Combined with the right incentives, improved price transparency could shift the behavior of providers, consumers and insurers, enabling the nation to save $100 billion over 10 years, according to one estimate.[2] Though that’s a modest one-quarter of one percent of total health care spending, it still represents significant savings; for Oregon that would have reduced health care spending by $80 million in 2014.[3]

Oregon policymakers, hospitals and health care providers have made modest improvements in price transparency in recent years. However, Oregon should pursue additional measures to improve the visibility of prices for patients, providers and health plans.

Greater price transparency has the potential to play a role in controlling health care costs by influencing the behavior of patients and providers.

- Patients currently make limited use of price transparency information for a variety of reasons. Existing price information is often not easily accessible or customized to the particular patient, and is rarely provided at the right time to help inform consumer decision-making. Even when price information is available, health plans often are not structured to provide meaningful benefits to consumers who act on it.[4] In addition, patients’ perception of quality or their loyalty to current care providers may dampen their interest in using price transparency tools.

- When patients use price transparency information to choose less expensive providers, they can reduce their health care spending. For example, a study of price-shopping by patients insured by 18 large employers found that patients who used the transparency tool reduced total health care spending by 14 percent for lab tests and 13 percent for advanced imaging services.[5]

- With the right incentives and information, patients may use price transparency information to seek care from less expensive providers, and in response, higher-cost providers may choose to lower their prices to remain competitive. This can deliver system-wide cost savings. For example, higher-priced providers of MRIs in five metropolitan areas lowered their prices after an insurance company began an aggressive price-transparency effort and helped patients who needed elective MRIs schedule with lower-priced providers.[6]

Price transparency is also important for health care providers and insurers. Providers influence or directly make a large share of health care decisions and spending, often without knowing in advance the price other providers, such as labs, charge customers and insurers. Insurers can use increased transparency to influence how much providers choose to charge for their services.

- Numerous studies, conducted primarily in hospitals, have found that knowing the price of lab and imaging tests prompts providers to order fewer tests. For example, when hospital-based health care providers were shown the price of lab tests as they ordered them, the number of ordered tests declined by 8.6 percent, which reduced charges by $400,000 over six months.[7]

- Outside of hospitals, such as in a primary care setting, price transparency does not appear to change how providers order lab tests and imaging, though this has been less studied than price transparency in hospitals.

- Information about prices can help insurance companies design insurance plans that encourage patients to choose lower-priced providers and may cause some providers to lower their prices. For example, insurance companies in New Hampshire have developed tiered-pricing plans that reward members for choosing high-value providers and charge patients much higher out-of-pocket fees for using the most expensive laboratories and outpatient surgery centers, which are usually affiliated with hospitals. As patients have reduced their use of higher-priced options, some hospitals have agreed to reduce their prices for lab services, outpatient surgery and other care.[8]

If poorly implemented, however, price transparency has the potential to increase rather than decrease health care prices and spending. This risk can be mitigated by how price data is presented or released.

- Though medical researchers have found no consistent link between the cost and quality of health care, a sizeable minority of patients may assume that higher-priced care is higher-quality care.[9] Thoughtful design of price transparency tools to include data on quality of care can reduce the extent to which consumers are inclined to use price as a measure of quality.[10]

- The Federal Trade Commission has expressed concern that increased price transparency could lead providers to increase their prices, either through reduced willingness to negotiate discounts or through tacit price collusion.[11] One way this potential problem can be avoided is to release data that are more than a year old so that providers lack sufficient information to match competitors’ current prices.

Oregon must do more to improve price transparency for consumers.

- As a basic consumer right, patients should be able to ask for and receive information on the likely price of care at the “point of purchase.” Doctors’ offices, hospitals and imaging facilities should be required to provide the likely price of care if a patient asks for an estimate.

- Oregon policymakers should require that information collected in the state’s all payer-all claims database be made available to consumers, with data ideally disaggregated by payer, procedure and provider. This process could begin with the categories of health care that consumers are most willing to shop for, such as lab work and imaging studies.

- Oregon could explore the possibility of establishing benchmark prices for a wide range of procedures, drawing on data in the state’s all payer-all claims database. These reference prices would give consumers a benchmark against which to evaluate a price estimate from a provider and provide a sense of how much a patient might pay for quality care.

- Oregon should ban gag clauses that prohibit insurance companies or providers from revealing the prices they have negotiated with each other, as that may limit the comprehensiveness of third-party price transparency websites, such as Castlight, HealthSparq and ClearCostHealth.

Policymakers could also pursue options to improve price transparency for providers. For example, Oregon should explore requiring hospitals to include an estimated price for laboratory and imaging tests in electronic health record systems so that providers can see that information when ordering.

Oregon should pursue measures to ensure that greater price transparency does not have the undesirable consequence of increasing prices. To start, the state should ban “most-favored nation” agreements between providers and health insurers, in which a provider, after negotiating a price with an insurer, agrees not to offer any competing insurer a lower price. Most-favored nation agreements can inflate health care prices even with current, limited price transparency, and should be banned.

[1] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group, National Health Expenditure Data: Health Expenditures by State of Residence, June 2017, available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsStateHealthAccountsResidence.html.

[2] Chapin White et al., West Health Policy Center, Healthcare Price Transparency: Policy Approaches and Estimated Impacts on Spending, May 2014, available at http://8637-presscdn-0-19.pagely.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Price-Transparency-Policy-Analysis-FINAL-5-2-14.pdf.

[3] Assumes one-quarter of one percent is annual average savings. Oregon spent $31.9 billion on health care in 2014: See note 1.

[4] Anna Sinaiko and Meredith Rosenthal, “Examining a Health Care Price Transparency Tool: Who Uses It and How They Shop for Care,” Health Affairs, (35(4):662-670, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0746, April 2016.

[5] Christopher Whaley et al., “Association between Availability of Health Service Prices and Payments for These Services,” JAMA, 312(16):1670-1676, doi: 10/1001/jama.2014.13373, 22/29 October 2014.

[6] Sze-jung Wu et al., “Price Transparency for MRIs Increased Use of Less Costly Providers and Triggered Provider Competition,” Health Affairs, 33(8):1391-1398, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0168, 2014.

[7] Leonard Feldman et al., “Impact of Providing Fee Data on Laboratory Test Ordering: A Controlled Clinical Trial,” JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(10):903-098, doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.232, 2013.

[8] Ha Tu and Rebecca Gourevitch, California HealthCare Foundation and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Moving Markets: Lessons from New Hampshire’s Health Care Price Transparency Experiment, April 2014, available at http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20M/PDF%20MovingMarketsNewHampshire.pdf.

[9] Kathryn A. Phillips, David Schleifer and Carolin Hagelskamp, “Most Americans Do Not Believe that There Is an Association between Health Care Prices and Quality of Care,” Health Affairs, 35(4):647-653, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1334, April 2016.

[10] Judith H. Hibbard et al., “An Experiment Shows that a Well-Designed Report on Costs and Quality Can Help Consumers Choose High-Value Health Care,” Health Affairs, 31(3):560-568, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1168, March 2012.

[11] Marina Lao, Director, Office of Policy Planning; Deborah L. Feinstein, Director, Bureau of Competition; and Francine Lafontaine, Director, Bureau of Economics, Federal Trade Commission, Letter to The Honorable Joe Hoppe and The Honorable Melissa Hortman, Minnesota House of Representatives, Re: Amendments to the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act Regarding Health Care Contract Data, 29 June 2015, available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/advocacy_documents/ftc-staff-comment-regarding-amendments-minnesota-government-data-practices-act-regarding-health-care/150702minnhealthcare.pdf.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Elizabeth Berg

Policy Associate

Find Out More

How to curb health care costs

Unhealthy Debt

What the coronavirus pandemic means for overall health care costs