What the coronavirus pandemic means for overall health care costs

In a previous blog post, I explored how the coronavirus pandemic might affect health insurance and coverage. Here, I want to explore some questions about how the coronavirus will affect health care spending overall and by governments, and the health care system itself.

-

How many health care providers will go out of business or consolidate into bigger networks?

-

How will governments deal with the budgetary strain of increased public health care spending?

Where will we see price gouging?

I expect that some actors who already have excess power in our broken health care market will abuse their power to boost their profits. For example, there’s potential for price gouging around coronavirus testing. For COVID-19 testing that is covered at no cost to patients, the insurer must pay the rate specified in its contract with the provider. But if there is no contract, the insurer must pay the cash price posted by the provider. Some providers and/or test-makers will abuse this and post cash prices that are way too high.

Abusive pricing practices might occur around treatments and vaccines, too. For example, pharmaceutical company Gilead requested “orphan” drug status for its existing drug remdesivir, which may help treat COVID-19, though the company subsequently rescinded its request after widespread criticism. Orphan drug status would have given the company years of monopoly control over pricing for the drug and protection from generic competition. Though the risk of this has dropped with remdesivir, other abusive pricing could happen with a different drug. And at some point, a drug company will develop a vaccine. Until and unless there are multiple vaccines available, the manufacturer potentially could charge a small fortune for each dose.

Improved transparency of drug prices will help reveal whether companies are taking advantage of the coronavirus pandemic to raise prices. Several states have adopted price transparency requirements that may help policymakers track price changes.

How many health care providers will go out of business or consolidate into bigger networks?

Massive disruptions in health care because of the coronavirus may cause provider closures or consolidation, which could increase health care costs.

Hospitals, clinics, physicians’ practices and almost all health care providers have lost a large portion of their income in the past month because of the coronavirus pandemic. Providers and hospitals are postponing non-essential care to avoid exposing patients or providers to the coronavirus and in anticipation of a wave of very ill patients. This has decimated the budgets of many facilities, including rural hospitals, health care centers, dentist offices and pretty much every kind of medical provider. Here’s a map that projects how many family medicine offices could close by the end of June, due to lost revenue, cuts to hours and staffing, or reassignment of staff to hospitals overflowing with COVID-19 patients.

Furthermore, if the number of uninsured patients increases, hospitals that provide care to people who have no other health care option will face additional financial strain. Though federal relief bills have included at least $100 billion for hospitals and health care providers and President Trump has promised that the federal government will pay hospitals for treating uninsured COVID-19 patients, hospitals may face other unreimbursed costs. Hospitals must provide emergency care to all patients, regardless of their ability to pay, and if the number of uninsured patients rises hospitals will end up caring for patients with heart attacks, mental health crises or other non-COVID-19 ailments who cannot pay for care.

Providers in financial distress may close permanently, merge with another provider, or get bought out by a bigger player, such as a hospital network, an insurance company or even a private equity firm. Closings and consolidation will be bad for reducing the high cost of health care, because past experience shows that provider consolidation results in higher prices.

How will governments deal with the budgetary strain of increased public health care spending?

Caring for COVID-19 patients has the potential to greatly increase health care spending by states and the federal government.

The worst-hit patients are older and thus covered by Medicare. One estimate says that COVID-19 spending could equal up to 28% of current Medicare spending. That estimate, from early March, pre-dates the extensive social distancing precautions ordered by governors, which have helped reduce the number of people who have gotten sick, and so the total cost to Medicare may be lower.

Medicare’s hospital insurance fund was already expected to have expenditure greater than revenues by 2026, due to a long-term increase in health care costs and demographic changes that result in a declining number of people working relative to the number who receive Medicare. Will a sharp one- or two-year increase in spending related to COVID-19, coupled with a drop in payroll tax revenues as the unemployment rate rises, bring that insolvency date closer?

Insolvency doesn’t mean that Medicare won’t be able to pay any bills. Rather, it means that policymakers will need to find ways to reduce spending or increase revenue. There’s no painless way to do either, and ideological biases will make this a very hard set of choices to navigate. That’s why years of consistent warnings that Medicare requires some adjustments haven’t led to any long-term changes, but only short-term steps to balance spending and revenue. Leaders could choose this same approach in response to COVID-19, or the crisis could create an opening for more dramatic changes.

Federal health care spending will increase outside of Medicare as more people lose their jobs and purchase subsidized health insurance through the Affordable Care Act — or their income drops so low that they qualify for Medicaid. In both cases, the federal government incurs the majority of the cost. This cost will rise faster if there’s a big price jump for insurance plans sold through the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces and consumers require larger subsidies to limit the total share of their income they spend on insurance.

Rising enrollment in Medicaid will also affect state government spending, since states pay a share of Medicaid costs. The federal government pays for 50 to 77 percent of Medicaid expenses, while states cover the rest. As a result, rising Medicaid enrollment means states will need to spend more on health care at the same time that their tax revenues are falling. This will force states into difficult decisions such as narrowing eligibility for Medicaid enrollment, reducing how much care Medicaid will cover, and funding other important public services, such as education.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, I was alarmed that the nation spent nearly 18 percent of GDP on health care. That represents a huge financial burden for families, for governments, for employers and for society as a whole. The abrupt and challenging change to our health care needs and the overall economic picture because of the coronavirus threatens to make the financial cost of our health care system even more painful. The questions that I’ve raised here will help us begin to understand the extent of the new challenges we face.

Photo: Fort Belvoir Community Hospital. Reese Brown/U.S. Army.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

What the coronavirus pandemic means for health insurance

How to curb health care costs

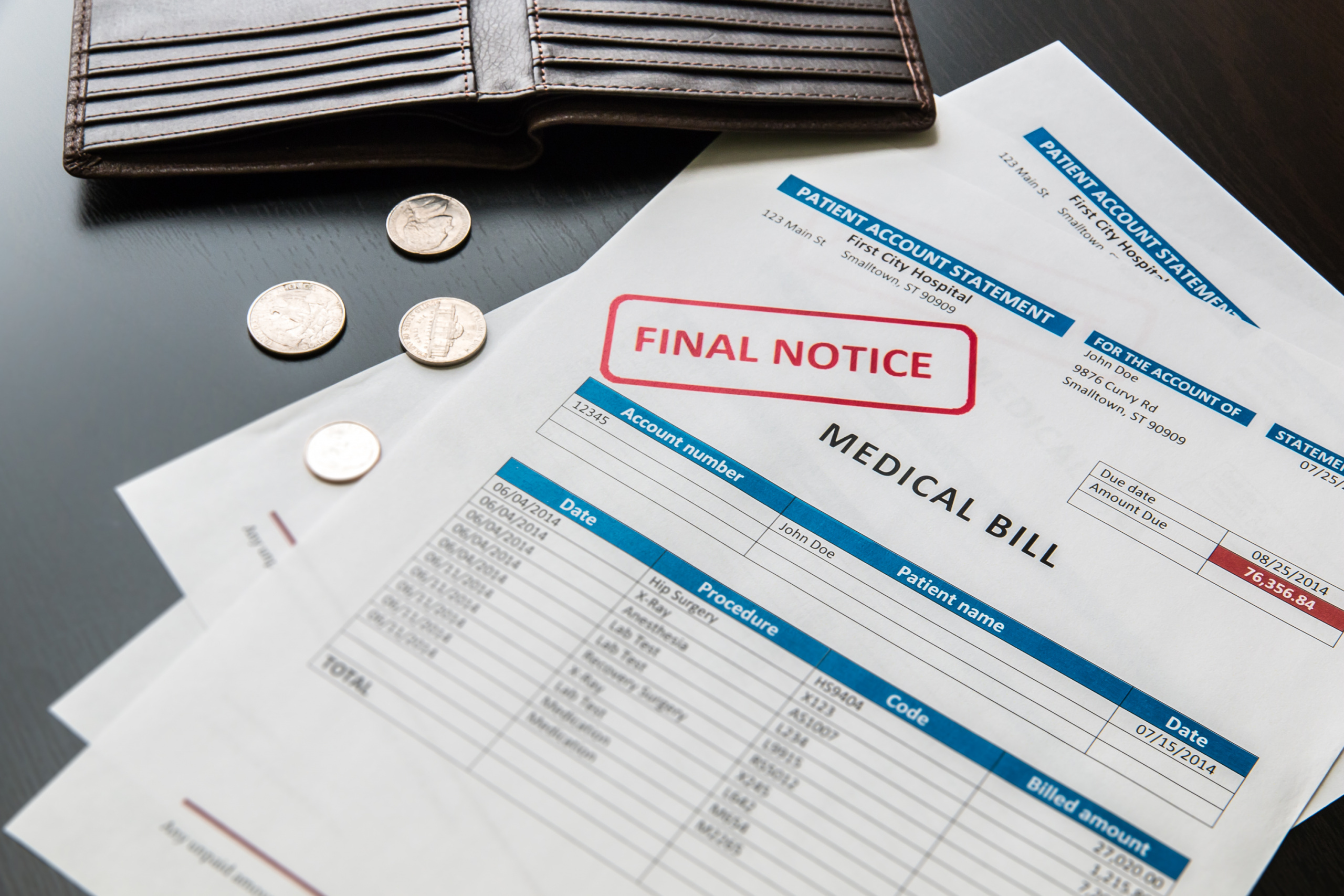

Unhealthy Debt