The Problems of Industrial Agriculture, Now and for the Future

Agriculture in the U.S. is dominated by large, specialized crop and animal farms. These industrial farms focus on short-term productivity, often at the cost of creating environmental and public health problems.

Agriculture in the U.S. is dominated by large, specialized crop and animal farms. These industrial farms focus on short-term productivity, often at the cost of creating environmental and public health problems.

Our new report with the U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Reaping What We Sow: How the Practices of Industrial Agriculture Put Our Health and Environment at Risk, documents what the rise of large, specialized farms means for our health and our environment, and how it threatens long-term agricultural productivity.

The typical farm today grows just one or two crops, or raises one or two types of animals, and does so on a large scale. Corn is most often raised on a 600-acre field, up from 200 acres in the 1980s. The average hog is raised on a farm with 30,000 other hogs, a 24-fold increase since the 1980s. The nation’s agricultural system now produces more food than we can consume or than is good for us, and does so in a way that creates a number of threats to the environment and public health.

For example, by growing the same one or two crops year after year – most often corn and soybeans – industrial farms deplete nutrients in the soil. In response, they apply manure or synthetic fertilizer but too often this washes into waterways, where it feeds algal blooms that create dead zones or pollute drinking water. Farmers have the tools to reduce water pollution, including leaving grassy buffers between fields and waterways, planting cover crops, and tilling less often. However, federal farm policy, bank lending practices that favor large farm operations, and other technological and corporate forces encourage farmers to focus on maximizing short-term output rather than making these modest changes.

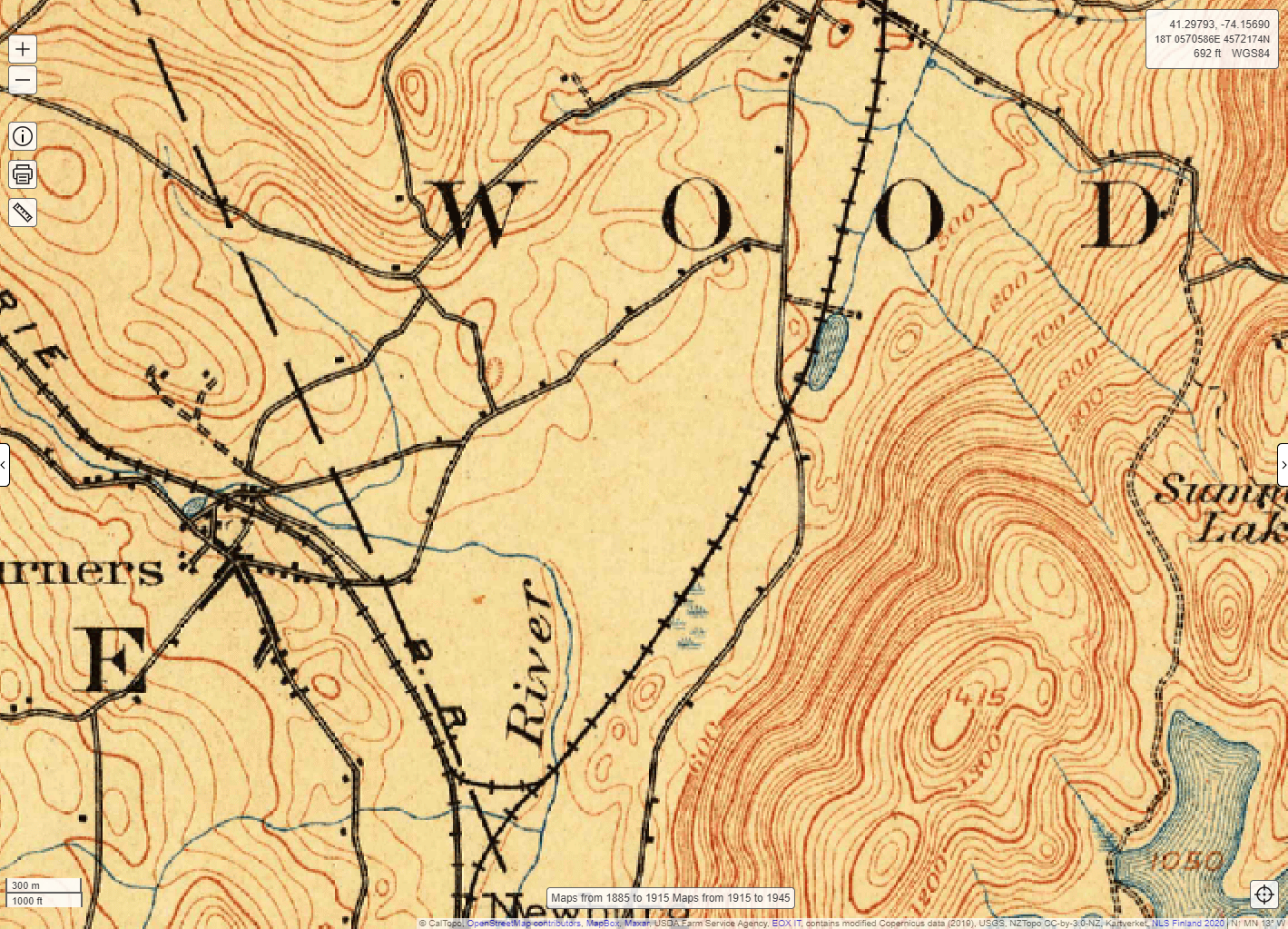

Conservation buffers, such as these hedges alongside Iowa’s Bear Creek, help prevent sediment and agricultural chemicals from contaminating water. Photo: Lynn Betts, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

In animal agriculture, the focus on short-term production also creates environmental and public health threats. For instance, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) operate by raising animals in confinement and feeding them grains. Because so many animals are kept in a limited area, often in unsanitary conditions that allow disease to spread quickly, operators of these farms may feed daily doses of antibiotics to their animals. This routine use of antibiotics on animals results in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can infect humans and are very difficult to treat. Farmers can raise animals without the routine use of antibiotics – in the near future, nearly half the chicken in this country will be raised without the routine use of medically important antibiotics – but federal policy gives them little incentive to do so.

Industrial farming practices also threaten the long-term viability of agriculture. Nutrients aren’t the only thing that run off from fields that lack grassy buffers or cover crops. Soil also washes into waterways. In the U.S., topsoil has been eroding from farms faster than it can be replaced, which threatens future crop yields. The same practices that help keep nutrients out of waterways can help keep topsoil in place.

One obstacle that keeps farmers from adopting better practices is federal agriculture policy that encourages, rather than discourages, some of the worst practices. Federally subsidized crop insurance, for instance, encourages specialization in corn and soy, despite its implications for water quality. A better approach would be to limit subsidized crop insurance to farms that implement measures to limit water pollution. By shifting key public policies, we can change how our food system operates to better protect public health, the environment, and long-term agricultural productivity.

Top photo: Karen Perhus via Dreamstime

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

When is enough enough? The “abundance agenda” America needs

Land use can change on a dime, but what’s the real cost?

Innocent until proven guilty works for people — not chemicals.