Sarah Nick

Policy Associate

The shopping centers we see in our communities haven’t always been there – but the environmental damage is sure to last.

Policy Associate

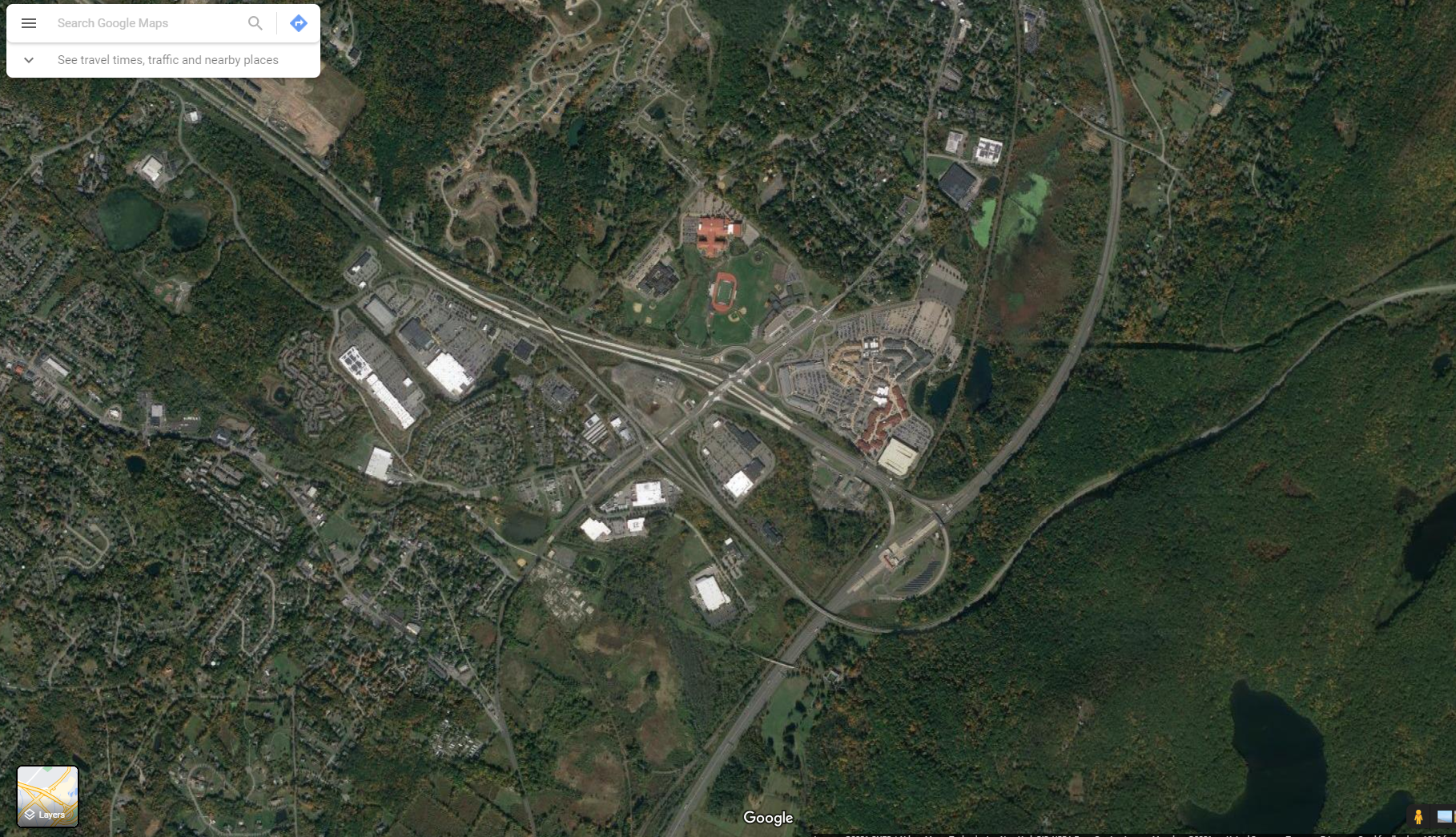

The Woodbury Common has been a presence in my hometown my whole life. A massive outdoor outlet mall, Woodbury Common spreads across an area of land a touch larger than that of an elementary, middle and high school, a football field and a few baseball diamonds combined. The mall is home to the largest collection of designer outlets in the world – stores that draw crowds of visitors, including international tourists taking a day trip from New York City for a shopping spree.

For years I’ve wondered what existed on that plot before it was built. Recently, I found an answer to that question by reaching out to the Woodbury Historical Society.

Situated in the valley of Bear Mountain, the land on which Woodbury Common now sits would have been fertile and well-watered. In the 1700s, the plot now owned by the mall was taken up by a few small family farms, a tavern and a family cemetery. We still know some of the names of the families that lived there: Dickerson, Peckham, and Taylor. The land remained in use for agriculture right up until the early 1980s, when the Harriman family, the last family to farm the land, gave the plot to the Town of Woodbury. The town subsequently sold the land to a chain outlet mall group for $930,000, and the mall has been there ever since.

The more I learned about this historical plot, the more I felt pride for what my community had once been. These family farms would have been too small and too far from the city to produce crops for more than their own families and the community. A far cry from today’s massive, polluting factory farms – this was a naturally sustainable, community-centric plot that had been productive, arable farmland for 250 years (and maybe longer) until retail came along and choked the life out of it.

The productive farmland that predated the mall will never be the same – nor will the surrounding environment. Acres of cement and asphalt prevent rain from filtering back into the groundwater aquifers that supply clean water to local wells; instead, the oil, heavy metals, antifreeze and other toxic fluids dripping from vehicles wash off the massive parking lots, with the wastewater flow contaminating local waterways. The soil itself has likely been heavily compacted, with very little organic matter (two conditions that make for terrible agriculture), and if the mall is demolished – as many malls eventually are – it may end up full of construction debris. Essentially, the land is detrimental to the ecosystem while in use and will become all but useless for anything naturally productive after it’s discarded.

As if the loss of natural land to this development wasn’t sad enough in itself, it’s made all the more devastating by the fact that all this destruction was for the sake of an establishment that may only last a few more years anyway. Across America, malls are failing, in part due to the growth of online shopping, and storefronts are shuttered left and right. A quarter of all American malls are expected to close in the next few years, and the country will be left with a collection of ghost town-esque buildings. Even for a mall as successful as the Woodbury Common, there’s no way of knowing how long it’ll last.

In 1986, Woodbury made the call that a shopping mall was more valuable than natural land. The town may have seen the decision as a great economic benefit to the community, or a way to create a tourist landmark by jumping on a trend. Many cities and towns have made similar decisions, trading something of enduring value for the promise (often illusory) of economic growth and prosperity for a few decades at most.

Sustainability is often understood in terms of the new things we choose to build or do. Renewable energy, electric vehicles and recycling methods are developed and deployed so that we can continue to live modern lives, but in a low- to zero-impact way. But sustainability is also about what we choose not to do or build.

Orange County, NY, continues to make decisions that show sustainability to be an afterthought. Most recently, against fierce opposition from many local residents, the county opened the gates of the New York Legoland theme park earlier this year, another highly-developed plot of cement.

The problem is clear – but so is the solution. With each proposed project, the future of our landscape needs to be considered in conjunction with our current needs and wants. When we properly judge the value of our land, those projects might change from malls to rain gardens, housing developments to protected lands, and highways to greenways. When we change the definition of development to include sustainability, our short-term wins become long-term successes.

Top image: The same area, 1885-1915. Peckman’s Pond sits directly west of the Port Jervis Rail Line and the plot now occupied by the mall. Image via SarTopo

Policy Associate