Alana Miller

Policy Analyst

As cities look for solutions to tackle climate change, air pollution, traffic and pedestrian deaths, they should move the cars causing those problems out of the way and let the buses through.

Policy Analyst

This piece originally appeared on Streetsblog Denver.

In recent years, fewer Americans have been taking public transportation. The ridership declines have sparked rightful alarm (along with some wrongheaded calls to abandon transit altogether).

At the same time, many local governments and transit agencies have seemingly chalked up disturbing ridership declines to national trends, or focused their attention well down the road on proposed hyperloops and self-driving cars, while Uber has dubbed flying taxis “the future of urban mobility.”

But there is no reason to be defeatist when it comes to transit ridership. Excuses and far-off tech fantasies are frustrating distractions from the conversation we should have in our cities: how to use the tools we already have to make transit service better. With the urgent imperative of acting on climate, tackling air pollution and solving a pedestrian safety crisis, we can’t afford to forget the basics.

It may be less flashy than a flying taxi, but the humble bus is key for building the transportation system we want – as long as cities prioritize them on our streets.

Public transportation remains the best way to move millions of Americans efficiently in and around our cities. By getting people out of cars and onto transit, we can reduce driving, free up space currently dedicated to parking, and expand people’s access to opportunities. Buses are the workhorse of our transit system, and routes can be added or expanded relatively quickly and inexpensively.

While buses offer many benefits, the majority of American buses are forced to compete with cars that often carry only a single passenger. Most streets in our communities are nearly entirely dedicated for the use of personal cars, making bus travel awkward and slow.

As buses try to pull up to a curb to pick up a group of people, they’re sometimes blocked by other vehicles, like delivery trucks or Lyft and Uber drivers waiting to pick up a single passenger. Since most buses are forced to leave the travel lane to access the curb, they often get stuck waiting to pull back into traffic. At lights, a bus with dozens of passengers might be forced to wait for individual cars traveling on the cross-street – often carrying fewer people through an intersection in an entire light cycle than are carried by a single bus.

The obstacles that a bus encounters at every step of its journey makes for slow going. In New York City (home of America’s slowest buses), NYPIRG’s Straphangers Campaign issues an annual “Pokey” award for slow bus service. The 2018 award went to a local Manhattan bus that averages 3.2 miles per hour – about the pace of walking. At this rate, “riding a bus can feel like being in a funeral procession,” remarked Gene Russianoff, the group’s founder.

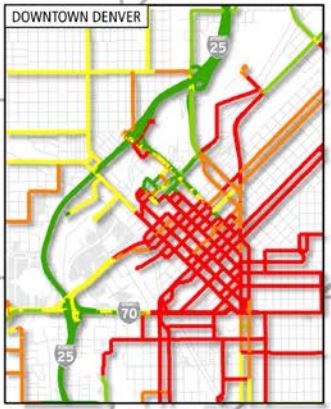

Other cities struggle with slow speeds as transit buses languish in local traffic. Analysis by Denver’s transit agency, RTD, in 2016 found that nearly every route in downtown clocked in slower than 10 miles per hour. In Los Angeles, average bus speeds have dropped by more than 13 percent since 2005. Speeds in Chicago have also been declining in recent years, with buses in some neighborhoods crawling along at 6 miles per hour.

Bus speeds in downtown Denver, where red is less than 10 mph. Source: RTD.

Slow buses, combined with other elements of poor service, are a critical factor in declining transit ridership across the country. Denver’s bus ridership fell between 2016 and 2017, and a TransitCenter survey of transit riders found that neglect of local buses may be to blame. Bus ridership in Los Angeles hit its lowest level in over a decade in 2016, while New York City’s bus ridership fell 6 percent from 2017 to 2018, and Chicago residents took 25 million fewer bus rides in 2015 than in 2013. In London too, analysis found that bus ridership has fallen fastest on routes where speed dropped the most.

The good news is, there are many relatively simple, low-cost improvements that could allow the bus to transform our transportation system.

By dedicating space (one of the eight tools my colleague Tony Dutzik and I identified as critical for a low-carbon transportation system) on our streets to bus lanes, buses no longer have to fight through traffic caused by personal cars. Even where that isn’t feasible, bumping out the curb (see image) so buses don’t have to pull in and out of traffic also saves time. Cities can give buses priority at traffic signals (as Denver is doing at some intersections), so they spend less time at red lights and in traffic. When cities outfit buses with signaling equipment, the vehicles can prompt lights to turn green or give the bus a head start before cars. Speeding up the boarding process by letting passengers pay on the curb and enter through multiple doors also cuts down on the amount of time buses spend sitting at the curb and not moving. These are straightforward, proven approaches that can help speed up nearly every bus route.

Buses travel faster when given dedicated lanes and extended curbs that let buses to stay in the travel lane instead of pulling into a recessed curb to pick up and drop off passengers. Photo: NYC DOT

Taken all together, improvements to create “bus rapid transit” on major routes can transform a city’s bus system, making those bus lines as reliable as rail and attracting more bus riders. Around the country, while ridership has been falling on local bus routes, bus rapid transit lines have seen consistent ridership increasessince 2012. In Minneapolis / St. Paul, ridership on the A-Line express bus corridor is one-third higher than it was in 2015 before bus rapid transit treatments. A 21 percent increase in transit ridership in Richmond, VA has been attributed to a new 7-mile bus rapid transit line and network-wide bus improvements. Eugene, Oregon’s Green Line boosted speeds from 11 miles per hour to 15 and increased ridership 75 percent since it was launched in 2007. And Connecticut’s CTFastrack has helped to nearly double ridership in its corridor over the past four years.

Seattle, a city that has prioritized high-quality bus service, is one of the few cities in America where transit ridership is booming. In fact, in 2018 the city announced that its transit ridership was growing faster than anywhere else in the country, with regional ridership numbers at an all-time high. San Francisco’s bus ridership is up 19 percent since 2008, and the city has put forward a comprehensive plan to improve bus service.

To get people out of their cars and onto buses, bus service will not only need to be made faster, but also more frequent, and more affordable than driving. Riders need access to more frequent service – if a bus comes every half hour, it is hard to rely on, particularly when door-to-door rides are available at our fingertips and personal vehicles sit in our driveways. And, cities will need to make transit more attractive by pricing driving more appropriately – it currently can be cheaper to drive and park a car in a city than to take transit.

It’s not surprising – if public transportation is slow, infrequent, expensive, and inconvenient, people won’t take it. As cities look for solutions to tackle climate change, air pollution, traffic, pedestrian deaths and housing crises, they should move the cars causing those problems out of the way and let the buses through.

Policy Analyst