Alana Miller

Policy Analyst

Electric vehicles are an important tool for combatting global warming, and in order for California to meet its ambitious climate goals, many more Californians will need to choose EVs over gasoline-powered cars. Unfortunately, the day-to-day experience of EV drivers seeking to charge their vehicles has a long way to go to match the ease and convenience of refueling a gasoline-powered car – especially when it comes to public charging. California needs to support and require the installation of charging stations that are easy to use.

Policy Analyst

Vice President and Senior Director of State Offices, The Public Interest Network

Correction (Sept. 2019): The original version of this report erroneously cited a 2017 National Renewable Energy Laboratory report as indicating that California would need 35,000 fast-charging plugs to support the state’s 5 million zero-emission vehicle goal by 2030. While the citation was incorrect, more recent California-specific data suggest that the state will likely need well more than 35,000 fast chargers to meet its 2030 goals. The report has been corrected and updated accordingly.

Global warming is already impacting California in devastating ways. In 2018, wildfires ravaged the state, with the deadliest wildfire in history, the Camp Fire, killing at least 85 people, and the largest wildfire ever recorded in the state, the Mendocino Complex, burning almost half a million acres.[1] For nearly seven years, the state has been experiencing a drought, which has greatly impacted agriculture and water resources.[2] At the same time, rising sea levels threaten coastal communities with flooding, erosion and mudslides.[3]

We must accelerate action to reduce emissions in order to protect our state. Transportation is now climate enemy #1, the result of California’s dependence on private gasoline-powered cars.[4] To prevent the worst impacts of global warming, we must reduce our reliance on cars and ensure that the cars we do use run on clean electricity.

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer many benefits for California, including cleaner air and the opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Electric vehicles are far cleaner than gasoline-powered cars, and produce less carbon pollution and fewer of the emissions that lead to smog and particulate pollution.[5]

California is a leader in the adoption of electric vehicles, accounting for half of America’s EV sales.[6] The trend is expected to continue as the state works to achieve its goal of 5 million zero-emission vehicles on California streets by 2030, up from 513,000 that had been sold in the state through 2018.[7]

In order to meet these ambitious goals, many more Californians will need to choose electric vehicles over gasoline-powered cars, which requires that owning an EV become just as easy, if not easier, than owning a gasoline car. Unfortunately, the day-to-day experience of EV drivers seeking to charge up their vehicles has a long way to go to match the ease and convenience of refueling a gasoline-powered car – especially when it comes to public charging.

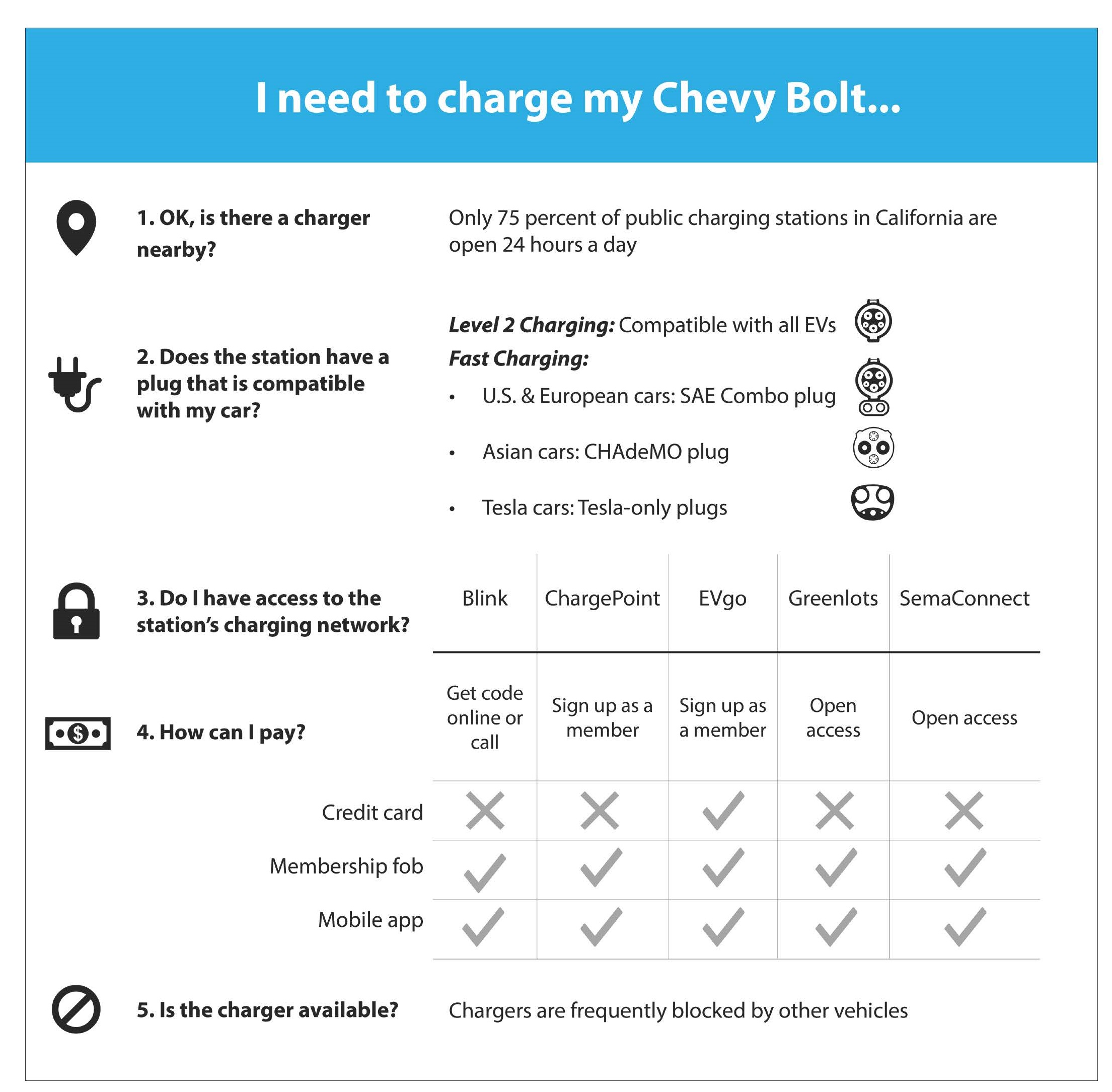

Only 75 percent of the public charging stations in California that are included in a Department of Energy database are open to the public 24 hours a day.[8] Only about 15 percent (750 stations) function with the ease of how we are accustomed to fueling vehicles – with the station open to the public 24 hours a day, compatible with different car types, and without requiring membership to a specific company’s network.[9]

People’s habits for charging their electric vehicles will be different from refueling their gasoline cars. Similar to how we charge our cell phones, most EV charging will happen overnight at home and during the day at work. Inconvenient or confusing public charging, however, still threatens to be a barrier to the mass adoption of EVs. California should use public policy tools and state investments in EV infrastructure to improve access to charging for all EV users.

Public charging is essential for the mass adoption of electric vehicles. Most electric vehicle owners need convenient access to public charging during longer trips and occasionally in daily driving. In addition, many residents of California who live in compact urban areas or multi-family housing do not have a driveway or garage and will have to rely on public charging to drive an electric vehicle. For instance, in a 2016 survey by the Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumers Union, only 54 percent of respondents reported having private off-street parking (like a garage or driveway) with an electrical outlet.[10] Even people with access to charging at home will use public chargers to make up for insufficient range or to provide a range buffer for their trip.[11]

California electric vehicle users often run into roadblocks or confusion when charging away from home. Among the challenges they face are:

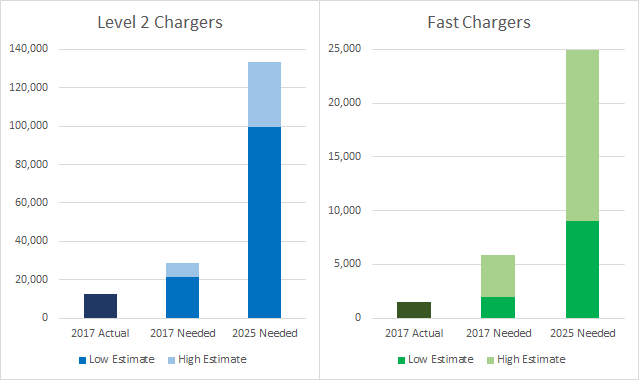

Too Few Chargers: Current numbers of electric vehicle chargers are insufficient to meet demand in California. Electric vehicle drivers report that chargers aren’t always in the areas where they need to charge or are often occupied. At of the end of 2017, the state had almost 14,000 public chargers, including 1,500 fast charging plugs, serving 350,000 plug-in electric vehicles.[12] However, according to a 2018 California Energy Commission report, California would have needed between 22,000 and 29,000 Level 2 plugs (not including chargers in private workplaces) and between 2,000 and 5,900 fast chargers to fully support that number of EVs.[13] Meeting the state’s ambitious goals for growing the electric vehicle market will require even more chargers. The same California Energy Commission report estimated that, to support 1.3 million zero-emission vehicles by 2025, the state would need 99,000 to 133,000 public and workplace Level 2 chargers, and 9,000 to 25,000 fast chargers. If the same ratio of chargers to vehicles were needed to support the state’s goal of 5 million zero-emission vehicles, California would require between 380,000 and 512,000 Level 2 chargers and between 35,000 and 96,000 fast chargers. (See Figure ES-1).[14]

Chargers that Are Not Available to the Public: Many charging stations can only be used by patrons of a business, by paying a fee for parking, or during certain hours. According to the Department of Energy’s database on electric vehicle charging stations, only 75 percent of public stations in California are open to the public 24 hours a day.[16]

Figure ES-1. Current Charging Infrastructure Versus the Infrastructure Needed to Support Current EV Numbers and 2025 EV Projections in California [15]

Incompatible Chargers: Certain chargers are not usable by some types of cars, with some fast-charging plugs (CHAdeMO) only working for Asian cars, others (SAE Combo) working on European and American cars, and Tesla’s proprietary connection only working on Teslas (see Figure 2). For instance, in downtown San Diego, an area with dense multi-family housing, there are only three fast chargers. One charger works with U.S. and European models, one works with Asian car models, and one works for Teslas.[17] Effectively, all electric vehicle owners in downtown San Diego, and those traveling into the city, have access to one fast charger.

Different proprietary networks: There are at least nine networks of EV charging stations in California. For an EV driver to use a network operated charging station, they often must be a member of that system or have the company’s app downloaded. This poses a challenge for EV drivers to find and use chargers.

Opaque pricing and multiple payment models: EV networks offer many different payment methods, including through a mobile app, credit card and in-vehicle purchasing. Some networks require purchases to be made within the app. Some stations charge a flat fee, some charge based on the amount of electricity used, and others charge by the length of time the car was charging. The cost of charging is not always clearly marked at the chargers, leaving drivers guessing how much they’ll end up paying. Comparison shopping across payment metrics is very challenging for the average EV driver looking for a charge, particularly when compared to the ease of understanding the standard metric of dollars per gallon at gas stations.

In order to meet California’s electric vehicle goals and replace gasoline-powered trips with electric-powered trips, people will need more convenient options for public charging.

The good news is that smart public policies can help streamline how we charge EVs, making it easier for more Californians to participate in the electric vehicle revolution.

There are five key strategies California should pursue to improve EV charging in the state and maximize the potential of electric vehicles:

——

Cover photo credit: Peter Petto/istockphoto

[1] – Deadliest: CAL FIRE, Top 20 Deadliest California Wildfires, accessed 7 December 2018, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20181204061326/calfire.ca.gov/communications/downloads/fact_sheets/Top20_Deadliest.pdf; Largest: Michael McGough, “Mendocino Complex, Biggest Wildfire in California History, Now 100 Percent Contained,” The Sacramento Bee, 19 September 2018, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20180926031857/www.sacbee.com/news/state/california/fires/article21865510.html.

[2] – The National Drought Resilience Partnership, Drought in California, accessed 7 December 2018, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20181023195817/www.drought.gov/drought/states/california.

[3] – Anne Mulkern, “Rising Sea Levels Will Hit California Harder Than Other Places,” Scientific American, 27 April 2017, archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20181205034029/www.scientificamerican.com/article/rising-sea-levels-will-hit-california-harder-than-other-places.

[4] – California Air Resources Board, “California Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventory – 2018 Edition,” archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20181110123720/www.arb.ca.gov/cc/inventory/data/data.htm.

[5] – U.S. Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center, Emissions from Hybrid and Plug-In Electric Vehicles, accessed 6 October 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20180214212424/www.afdc.energy.gov/vehicles/electric_emissions.php.

[6] – Veloz, Sales Dashboard, accessed 10 October 2018, at http://www.veloz.org/sales-dashboard.

[7] – Goal: Office of Governor Edmund G. Brown, Governor Brown Takes Action to Increase Zero-Emission Vehicles, Fund New Climate Investments (press release), 26 January 2018; Sold: Including plug-in hybrids and battery electric vehicles. Veloz, Sales Dashboard, 11 November 2018, available at http://www.veloz.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/11_nov_2018_Dashboard_PEV_Sales_veloz.pdf.

[8] – Stations may have multiple charging plugs. Alternative Fuels Data Center, Alternative Fueling Station Locator, accessed 12 October 2018, archived http://web.archive.org/web/20181012002402/www.afdc.energy.gov/fuels/electricity_locations.html

[9] – Ibid.

[10] – Consumers Union and Union of Concerned Scientists, Survey Methodology and Assumptions: Driving Habits, Vehicle Needs, and Attitudes toward Electric Vehicles in the Northeast and California, May 2016.

[11] – Michael Nicholas and Gil Tal, Survey and Data Observations on Consumer Motivations to DC Fast Charge, EVS30 Symposium, Germany, 9-11 October 2017.

[12] – Abdulkadir Bedir, et al., California Energy Commission, California Plug-In Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Projections: 2017-2025, publication CEC-600-2018-001, March 2018.

[13] – Ibid.

[14] – Ibid.

[15] – Ibid.

[16] – See note 8.

[17] – PlugShare, Locations 59159, 167951, and 15872, accessed 25 October 2018 at https://www.plugshare.com.

[18] – California Air Resources Board, SB 454 Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Open Access Public Workshop (presentation), 30 May 2018.

Policy Analyst

Emily is the senior director for state organizations for The Public Interest Network. She works nationwide with the state group directors for PIRG and Environment America to help them build stronger organizations and achieve greater success. Emily was the executive director for CALPIRG from 2009-2021, overseeing a myriad of CALPIRG campaigns to protect public health, protect consumers in the marketplace, and promote a robust democracy. Emily works in our Oakland, California, office, and loves camping, hiking, gardening and cooking with her family.