Overcharged: How state EV fees discourage clean choices

States are imposing hefty annual fees on electric vehicles, despite the benefits of EVs for air quality and the climate. Will those fees discourage Americans from "going electric"?

Frontier Group intern Brian Ly provided research and editorial assistance for this article.

The gas tax pays for the cost of building and maintaining America’s roads. Right?

Well, no. As we and others have shown, gasoline taxes and other so-called “user fees” associated with driving don’t come close to covering the great expense of maintaining America’s vast network of streets, roads and highways. Not only that, but, with rare exceptions, fuel taxes recoup none of the costs that gasoline- and diesel-burning vehicles impose on society through climate change, air pollution and other impacts.

The transition to electric vehicles creates the opportunity to reduce some of those massive societal costs. Electric vehicles are much more energy efficient, and produce less greenhouse gas pollution and fewer emissions that contribute to the formation of ozone smog. While EVs do impose some costs on society – including for construction and maintenance of the roads they use – any fair system of taxation would result in EV drivers being charged less per mile than drivers of gasoline-powered vehicles. Right?

In a large chunk of the United States, the opposite is true. Ten U.S. states currently charge typical EV drivers more in so-called “user fees” than they charge typical drivers of gasoline-powered vehicles. And when the societal cost of greenhouse gas emissions is factored in, nearly every state undercharges gasoline-powered vehicles relative to EVs.

To encourage a transition to cleaner travel, we need to rethink transportation finance.

The rise of state EV taxes

Drivers pay a variety of so-called “user fees” and taxes that are devoted, in whole or in part, to maintenance and construction of the road network. The most significant of these taxes are taxes on motor fuels, which are assessed by the gallon in all 50 states.

In recent years, however, revenue from motor fuel taxes has been growing very slowly – nowhere near quickly enough to keep pace with rising highway expenditures. Improved vehicle fuel economy, slower growth in the number of miles driven, and now the rise of EVs have cut into gas tax revenues. As those trends continue – and, in the case of EVs, accelerate – the gas tax will increasingly be unable to provide the level of funding to which transportation agencies have become accustomed.

There are many possible sources of revenue that governments can tap for transportation, as well as many opportunities for cost savings. But one answer to the so-called “funding gap” that has been adopted in at least 32 states has been to assess electric vehicle owners an annual tax on registration over and above that paid by drivers of gasoline-powered cars. These taxes vary from $50 to more than $200 per year.

In many cases, these state taxes exceed the amount of money that a typical driver, driving a typical gasoline-powered vehicle, would pay in gas taxes.

To compare how states tax drivers of EVs versus gasoline-powered vehicles, we looked up EV tax rates from the National Conference of State Legislatures and other sources, gas tax rates from the Energy Information Administration, and the average fuel economy of new U.S. cars from the Environmental Protection Agency. We also factored in per kilowatt-hour charges on public EV charging that are now charged by a few U.S. states, obtained from various sources. [1]

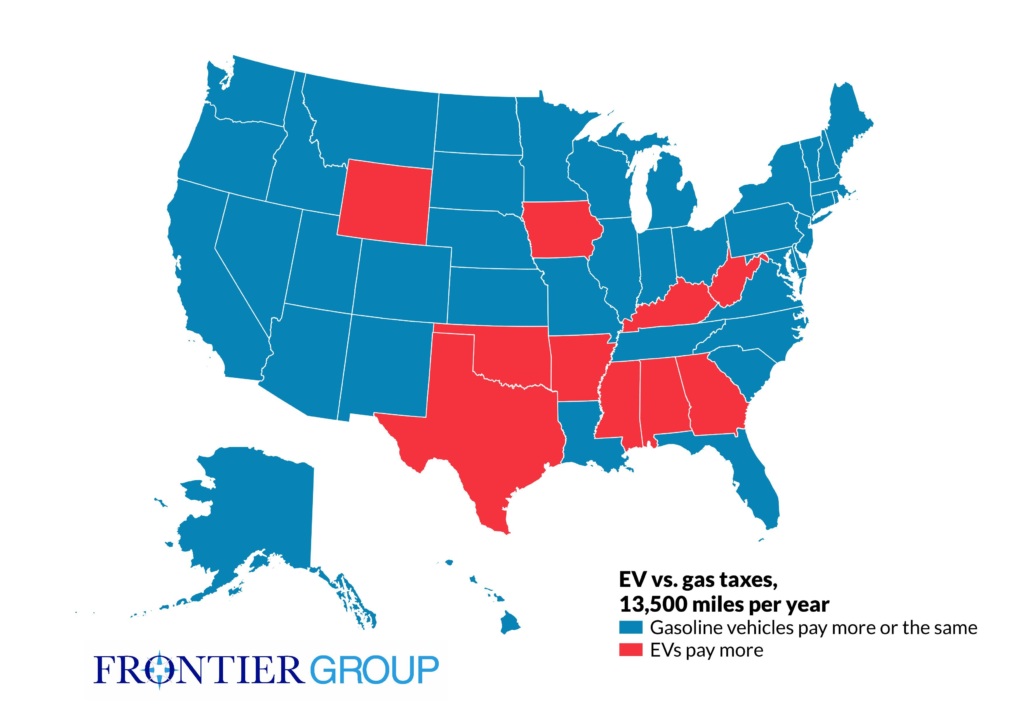

Where do Americans pay more to drive clean vehicles?

In 10 states, the driver of a typical new car traveling 13,500 miles per year will pay more in annual state EV taxes than they will in state gasoline taxes. And in a few states – Kentucky, Texas and Wyoming – a typical EV driver will pay in excess of 80% more in EV taxes than they would pay in state gas taxes if they drove a conventional vehicle.

Photo by Frontier Group | TPIN

An all-you-can-drive buffet

One of the benefits of the gasoline tax is that those who drive more pay more, and those who drive less pay less. This makes sense – people who drive more impose greater costs on the road system in terms of road damage and congestion.

State EV taxes do not work this way. While a few states give EV drivers the ability to opt into a pay-per-mile option, most assess a flat annual fee that does not vary with the number of miles driven.

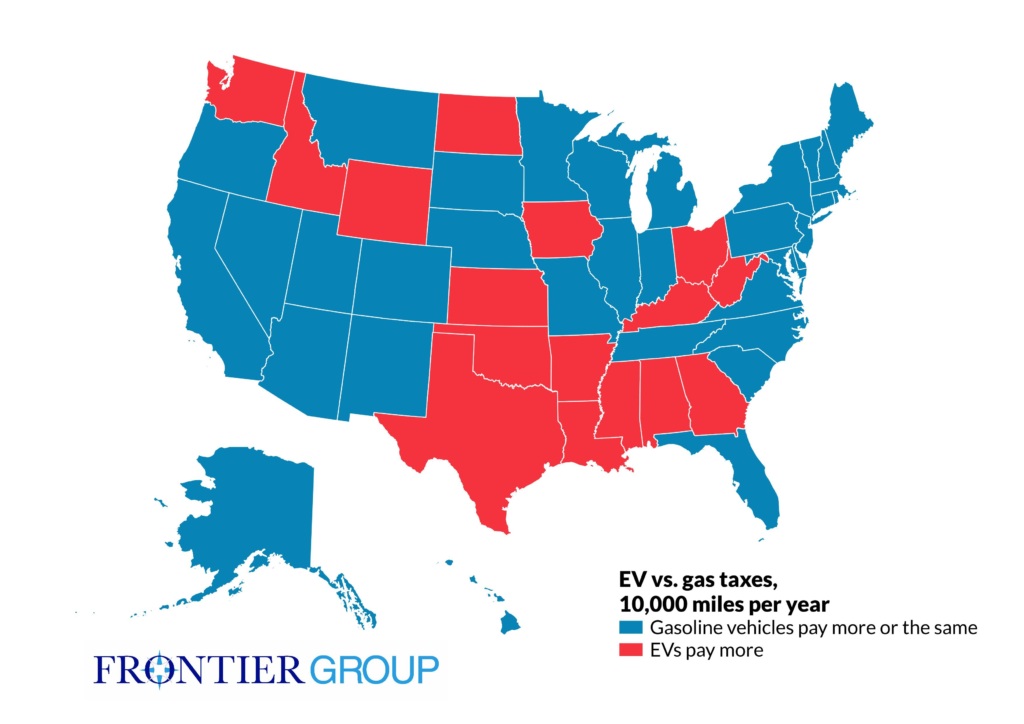

The result of this is that for those who drive fewer miles, state EV taxes are an even greater disincentive for EV adoption. Consider an EV owner who drives less than the typical number of miles each year – let’s say 10,000 miles as opposed to 13,500. That driver would pay more in taxes than the driver of a typical gasoline car in an additional six states (for a total of 16). These additional taxes – amounting, in some cases, to thousands of dollars over a vehicle’s lifetime – could severely undermine the economic case for “going electric” for many vehicle owners.

Photo by Frontier Group | TPIN

Other analysts have reached similar conclusions. A report earlier this month by Atlas Public Policy found that eight states charge EV drivers more in “user taxes” than drivers of typical gasoline-powered vehicles on the road today, but when comparing “fairness” on the basis of the energy consumption of the vehicles, every state assessing EV-specific fees overcharged EV drivers. Consumer Reports similarly concluded that some state EV fees are punitively high.

Paying for pollution

If EVs and gasoline-powered vehicles impose similar damage to the roads, there are other ways in which their impacts differ sharply, including their impacts on the climate and public health.

Climate change and air pollution are, first and foremost, human tragedies, but they also impose significant financial costs on society – costs that can be quantified.

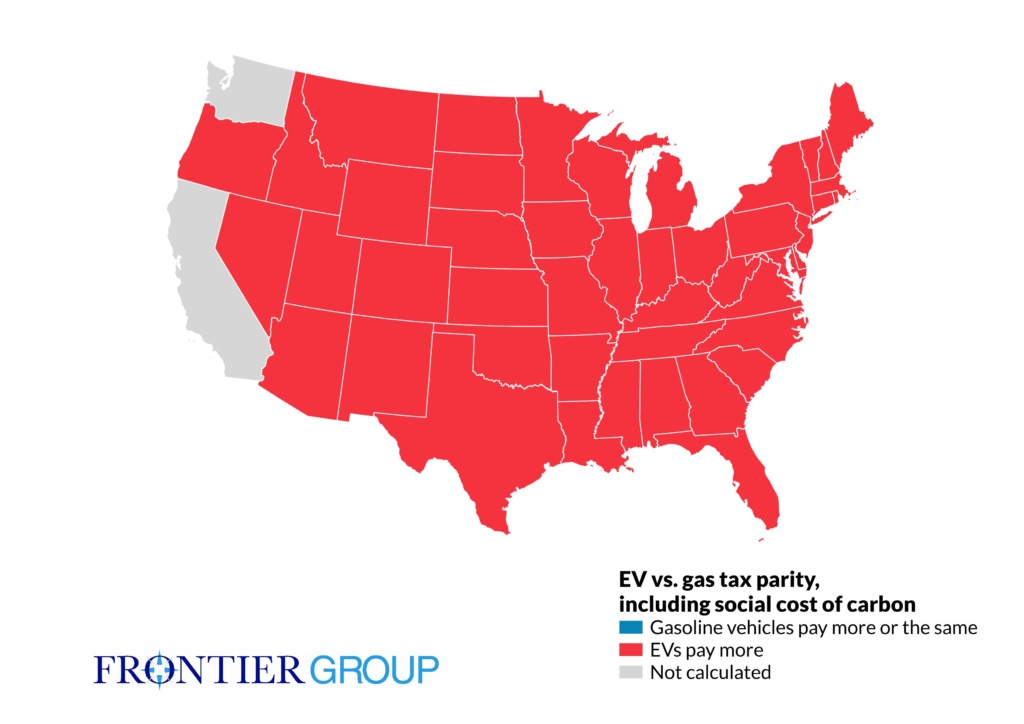

The federal government uses a measure called the “social cost of carbon” to quantify the impact of a ton of greenhouse gas emissions. Using emissions data for power plants from the EPA to estimate the per-mile emissions from EVs by state, and an estimated social cost of carbon figure of $185/ton (in line with current federal proposals to revise the social cost of carbon used in regulatory decision-making), gasoline-powered vehicle owners would pay less of their “fair share” of the societal costs of driving than EV owners in at least 46 states. [2] This includes states that do not currently assess a fee to EVs, but where combined state and federal gas taxes would not be high enough to recoup the social cost of carbon pollution.

Photo by Frontier Group | TPIN

In short, current U.S. gasoline taxes are so low that charging any EV fee at all represents an unjustified incentive to purchase and use gasoline-powered cars.

It’s time to shift gears

The current perverse system of taxation for EVs and gasoline-powered cars is a byproduct of a transportation finance system that was built to overcome the challenges of the early 20th century but is failing to meet the real and urgent needs of the 21st century.

In our 2022 white paper Shifting Gears we proposed an alternative model for transportation finance that charges users of various modes based on their impact on the transportation system, the environment and communities, and that eliminates outmoded restrictions on how transportation money is spent in order to focus resources on projects that deliver the greatest net benefit for society.

The current state approach to taxing electric vehicles risks not only further entrenching our outmoded, poorly designed transportation finance system for years to come, but also making it worse. While we will likely need to develop new tools to enable EV users to pay their share of the costs imposed by driving, forcing them to do so while simultaneously allowing users of gasoline-powered vehicles to escape those costs will only set us back.

Notes

[1] We did not include tax credits and upfront subsidies available to EV purchasers from the federal government and many states. This is for two reasons: First, not all EV purchases are eligible for federal tax credits and eligibility for state subsidies varies, so they cannot easily (or accurately) be factored into a comparison of costs between typical drivers of EVs and gasoline-powered vehicles. Second, states that provide upfront EV subsidies *and* assess annual EV fees essentially claw back the initial subsidy over time. The result is often a sort of time-delayed transfer of money from the state’s general fund to the state’s transportation fund. Factoring in the upfront subsidy would result in EV owners achieving something closer to parity with drivers of gasoline-powered vehicles, but the end result is a greater subsidy of highway users by general taxpayers – a different problem, but a problem nonetheless.

[2] This calculation includes both federal and state gas taxes. Alaska and Hawaii are excluded from this analysis. In California and Washington, the situation is complicated by carbon cap-and-trade programs that assess a carbon price to transportation fuels. These fees were not included in our analysis. The analysis also did not include the northeast’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, through which consumers of electricity – such as drivers of EVs – pay a carbon price but drivers of gasoline-powered vehicles do not.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

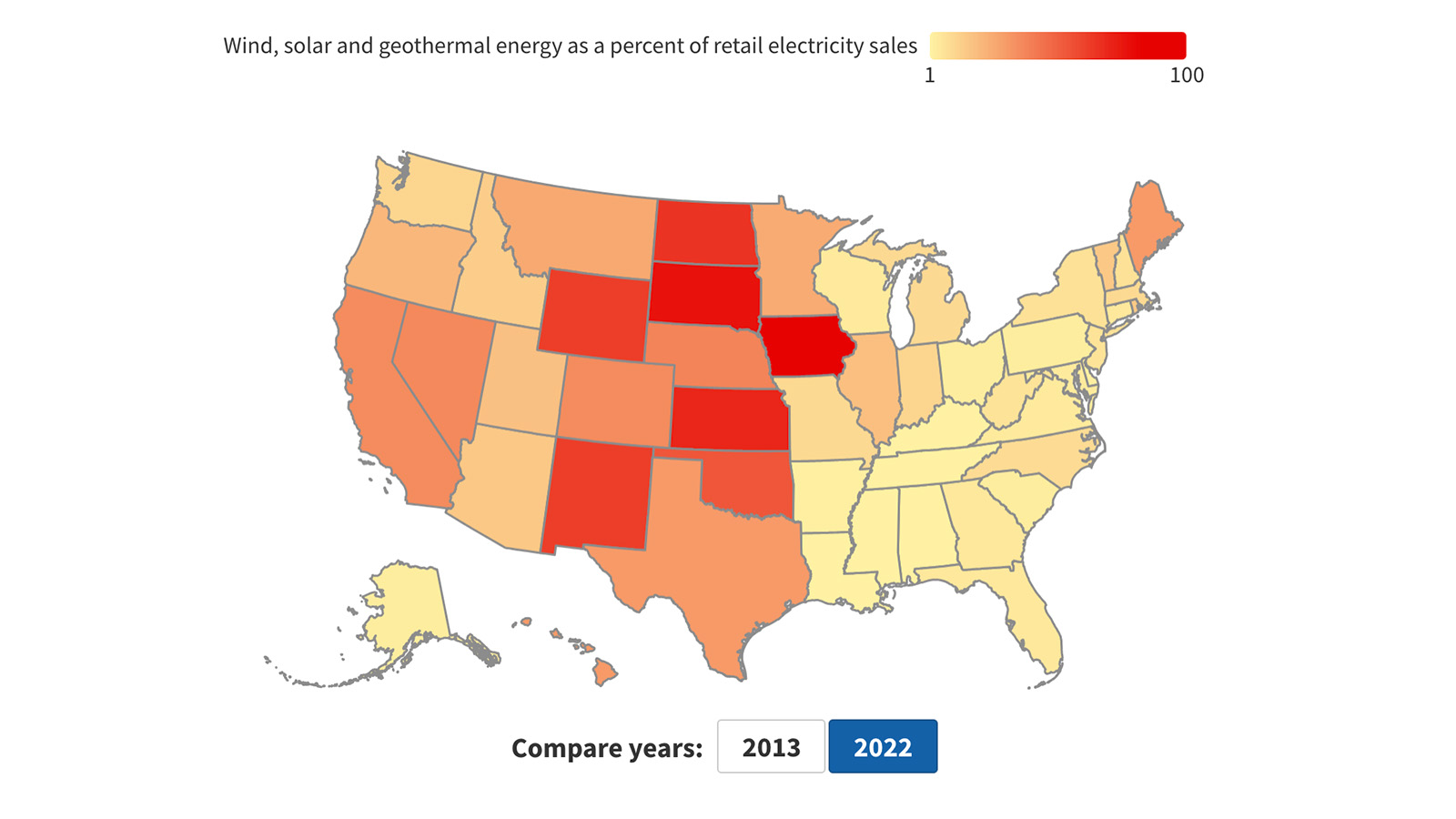

Renewables On The Rise Dashboard

Electric vehicles are good. We can make them better.

Electric Vehicles Save Money for Government Fleets