New Report: Cutting Pollution with Electric Vehicles

Battery-electric vehicles were an exotic sight just a few years ago. A parked plug-in hybrid electric Chevy Volt could draw stares from passersby, and the all-electric Nissan Leaf was an even greater oddity. Today, though, electric vehicles are common enough not to draw attention, as thousands of new electric vehicles are sold each month. As the number of electric vehicles on the road increases, so do the environmental benefits. Our new report, Driving Cleaner: More Electric Vehicles Mean Less Pollution, projects how the growth in electric vehicles could cut global warming pollution and help America get off oil.

Battery-electric vehicles were an exotic sight just a few years ago. A parked plug-in hybrid electric Chevy Volt could draw stares from passersby, and the all-electric Nissan Leaf was an even greater oddity. Today, though, electric vehicles are common enough not to draw attention, as thousands of new electric vehicles are sold each month.

As the number of electric vehicles on the road increases, so do the environmental benefits. Our new report, Driving Cleaner: More Electric Vehicles Mean Less Pollution, projects how the growth in electric vehicles could cut global warming pollution and help America get off oil. By 2025, widespread use of electric vehicles, coupled with a cleaner electricity grid, could reduce global warming pollution by 18.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, compared to conventional vehicles. That is equal to saving more than 2 billion gallons of gasoline per year.

While the emission reductions in 2025 are a good thing, the true benefit of getting more electric vehicles on the road by 2025 is that it will enable much steeper pollution cuts in subsequent years. By mid-century, climate scientists estimate that the United States needs to cut emissions of global warming pollution by more than 80 percent. To reach that goal, electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and fuel-cell vehicles will need to dominate the light-duty vehicle fleet – and those vehicles will need to be powered almost exclusively by emission-free electricity and other clean fuel sources. In California, for example, researchers have concluded that if the state is to achieve the emission reductions needed to avoid the worst impacts of global warming, electric vehicles and other zero-emission vehicles will need to account for 100 percent of new vehicle sales by 2040 and those vehicles will need to be charged with clean energy sources.

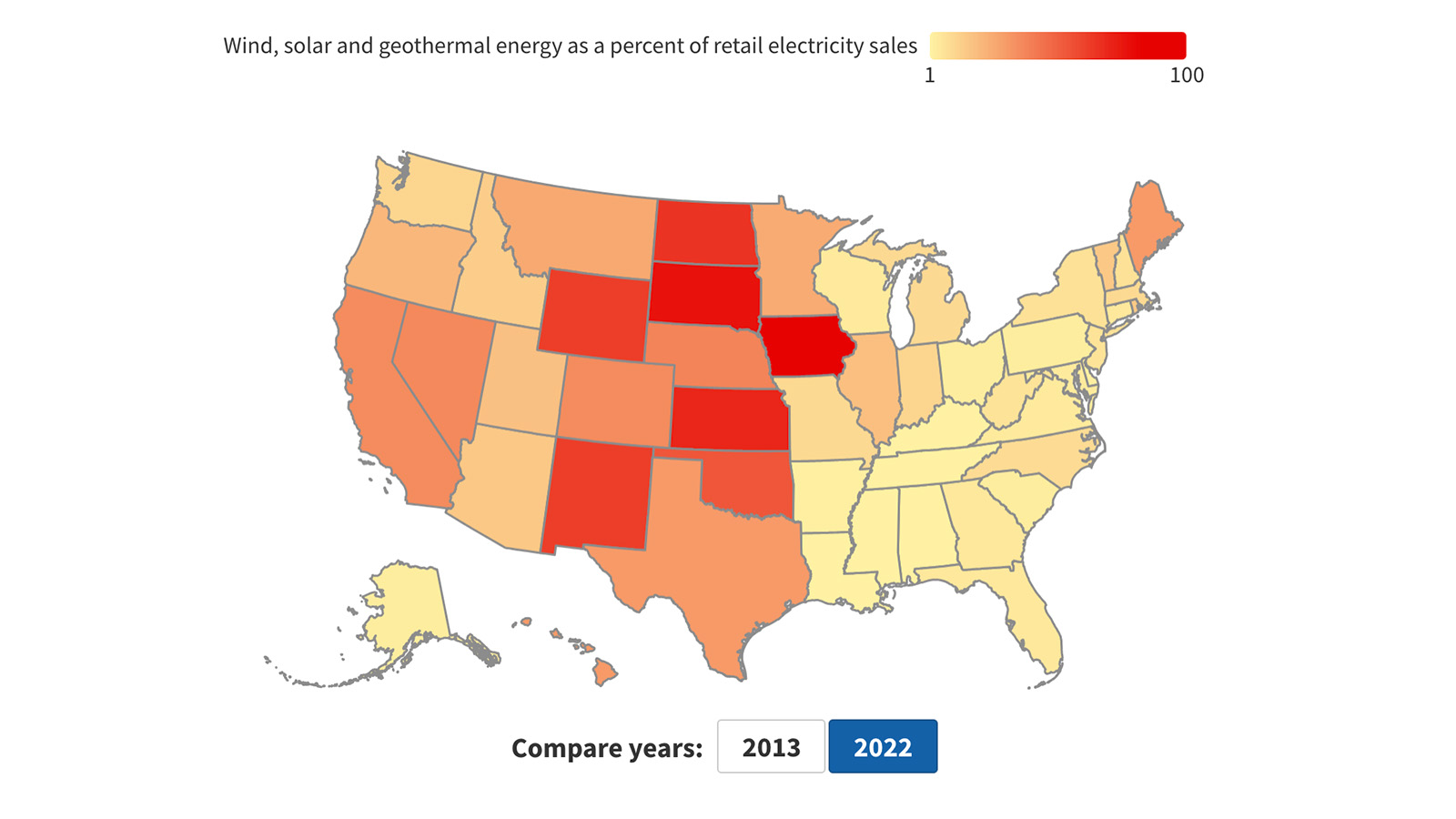

It is those long-term emission reductions that make policies promoting electric vehicles and clean, renewable electricity so critical. State and federal leaders can guide the transition to a cleaner transportation future by adopting policies that require the sale of more electric vehicles, that promote the development of wind and solar energy, and that limit use of the dirtiest sources of energy.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

Renewables On The Rise Dashboard

Overcharged: How state EV fees discourage clean choices

Electric vehicles are good. We can make them better.