Cutting through the Smoke

Why the Allegheny County Health Department Must Turn the Corner on Decades of Weak Clean Air Enforcement

Pittsburgh is no longer the “Smoky City” of days gone by, but pollution from industry continues to pose a threat to public health. Cutting Through the Smoke documents the health toll of industrial pollution in the area, the Allegheny County Health Department’s history of weak enforcement of clean air laws, and recent actions by the department that provide hope that air polluters in the county will finally be held accountable.

Downloads

Allegheny County has a long legacy of industrial air pollution. But while Pittsburgh is not the “Smoky City” of generations past, industrial air pollution still inflicts immense damage on the health of Allegheny County residents.

The Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD) is primarily responsible for protecting the people of Allegheny County from health-threatening air pollution. ACHD has been delegated authority to enforce the provisions of the federal Clean Air Act as well as local air pollution laws.

Yet for decades, some of Allegheny County’s biggest industrial facilities have continued to release excessive amounts of pollution into the air and to violate the terms of their emissions permits. Time and again, ACHD has acted slowly in response to air pollution complaints, relied on often-violated agreements negotiated with industrial facilities, failed to issue required air pollution permits on time, and failed to establish a credible threat of tough enforcement that would incentivize polluters to act more quickly to protect public health.

There are, however, signs of change. ACHD has recently stated its intention to move away from negotiated settlements, partnered with state and federal agencies and with citizens’ groups to enforce the law, and more fully used its authority to issue penalties to compel quicker action to cut emissions.

To ensure clean, healthy air for all residents of Allegheny County, ACHD must recognize the lessons of past enforcement failures and act promptly and aggressively against illegal polluters.

Poor air quality in Allegheny County puts the public’s health at risk.

- In 2016, the Pittsburgh area suffered from 121 days of elevated levels of ozone “smog” or fine particulate pollution in the air. The American Lung Association ranks the air in the Pittsburgh metro area the seventh-worst in the nation for year-round particulate pollution and 28th worst for ozone smog. Particulate pollution in the Monongahela Valley is among the worst in the country.

- Allegheny County is in the top 1 percent of counties nationwide for cancer risk from toxic air pollutants released by stationary point sources of emissions, such as industrial facilities, according to 2014 data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA).

- The Pittsburgh metro area ranks fifth in the nation for excess mortality from exposure to ozone and particulate matter, with an estimated 232 premature deaths annually.

- Allegheny County’s air pollution harms public health, especially the health of children, the elderly and those suffering from respiratory disease. A 2017 study found that 39 percent of school children in areas of Allegheny County near major industrial pollution sources were exposed to levels of pollution in excess of U.S. EPA guidelines. Twenty-two percent of children in those areas had asthma – a rate nearly three times the national average.

Industrial polluters are a major source of the air pollution that jeopardizes the health of Allegheny County residents.

- Industrial facilities were the biggest source of sulfur dioxide and fine particulate (PM2.5) emissions, and the second-biggest source of smog-forming nitrogen oxide emissions in Allegheny County in 2014.

- Pollution from point sources (including industrial facilities) accounts for nearly one-third of the cancer risk posed by hazardous air pollutants in Allegheny County.

- Industrial pollution harms public health across Allegheny County but is especially dangerous in communities near the plants themselves.

- A 2012 study found that concentrations of coarse particulate matter (PM10) in Braddock were highest in the area immediately surrounding U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Plant.

- A 2013 study by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh identified a set of census tracts in the industry-heavy Monongahela Valley that ranked high for cancer risk from hazardous air pollutants.

- A 2010 study by ACHD found levels of manganese and lead in outdoor air at Highlands High School in Natrona that exceeded federal safety standards. The elevated pollution levels were correlated with operations at a nearby ATI plant.

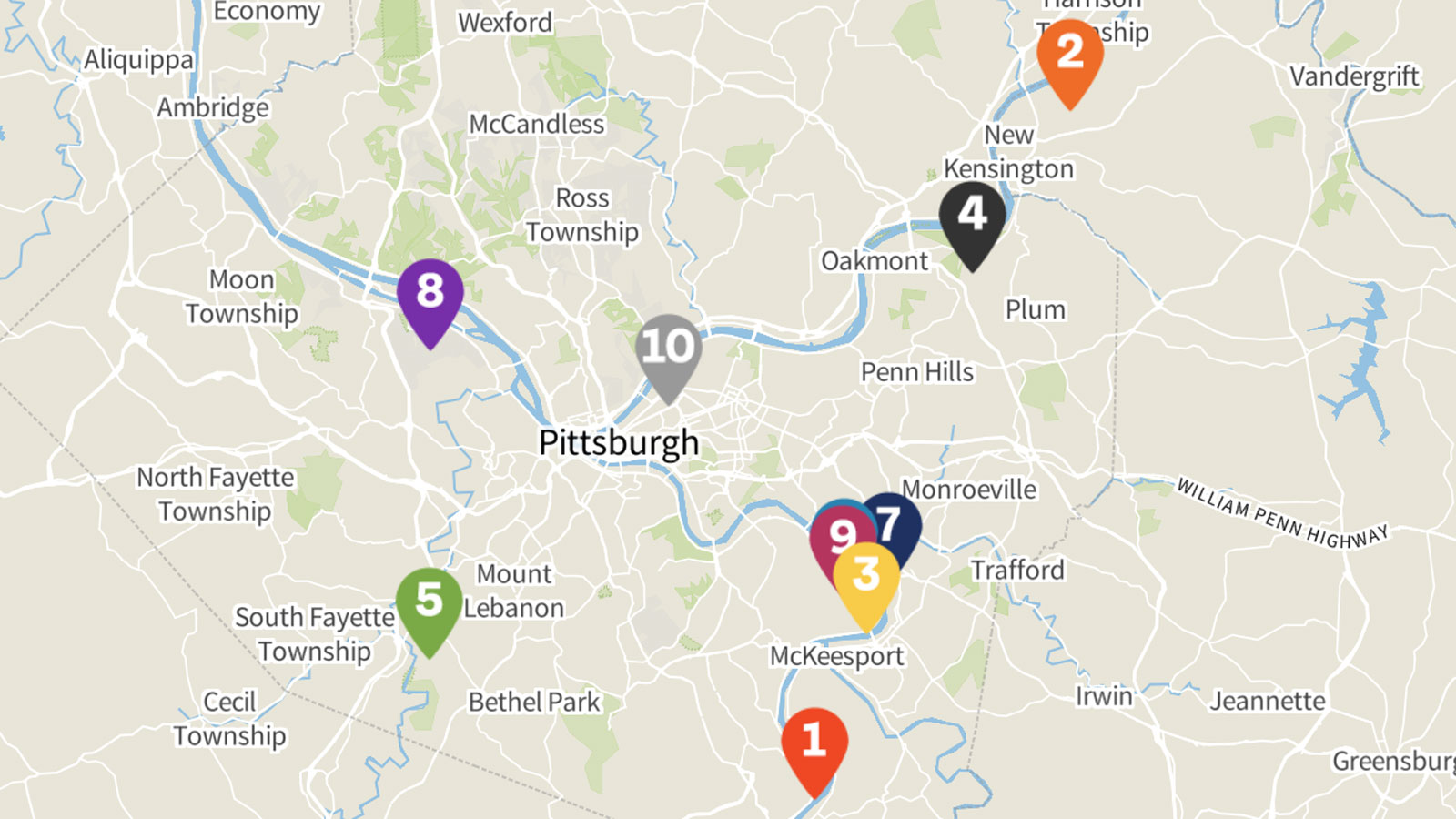

The history of seven polluting industrial facilities in Allegheny County illustrates the damage done by ACHD’s lackluster approach to environmental enforcement.

- U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works has racked up so many violations of clean air rules since 1990 that it has been the subject of more than 80 government enforcement actions and notices of violation. Over the years, ACHD and U.S. Steel have negotiated a series of consent orders in which U.S. Steel has pledged to make improvements at the facility and bring it into compliance with clean air laws. Those agreements, however, have often been violated, and the Clairton Coke Works remains one of the county’s largest polluters, putting the health of Monongahela Valley residents at risk. A December 2018 fire that knocked out critical emission control units – the second such outage in a decade – triggered 10 exceedances of federal health standards for sulfur dioxide over a span of 14 weeks, and led ACHD to warn Mon Valley residents to limit their outdoor activity.

- U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Plant in Braddock has violated clean air standards – especially limits on visible pollution from the plant – repeatedly over the last 40 years. Yet, despite a series of negotiated consent orders and financial penalties – and despite the public health toll of the plant’s pollution on nearby neighborhoods – it has continued to exceed its emission limits, leading ACHD to finally issue a notice of violation in late 2017.

- ATI Flat Rolled Products in Brackenridge (formerly Allegheny Ludlum) has been the target of at least 40 clean air enforcement actions and notices of violation since 1990, according to U.S. EPA records. The facility was allowed to exceed permitted levels of sulfur dioxide for more than a decade and then received a mere $50,000 penalty from ACHD, a penalty that was only issued after environmental and public health advocates announced their intention to sue to enforce the law.

- Harsco Metals in Natrona processes steel slag from the neighboring ATI Flat Rolled Products plant – a process that creates dust that has coated cars and children’s toys and play equipment in nearby neighborhoods. Harsco’s releases of toxic metals such as chromium, manganese and lead contribute to an overall toxic risk from air emissions that is 200 times as great as the risk posed by the typical industrial facility in Allegheny County, according to the U.S. EPA. The dust problem continued for more than a decade after the U.S. EPA and ACHD first took enforcement action in 2007, suggesting that ACHD’s enforcement strategy was ineffective in protecting the public’s health.

- Eastman Chemicals and Resins in West Elizabeth is a major source of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides (NOX) and hazardous air pollutants. However, ACHD has yet to issue the facility a Title V operating permit, which is required by the Clean Air Act and is a critical tool for public accountability and effective enforcement of the law. ACHD has long struggled with issuing permits to air polluters in a timely manner, a failing that was called out in a 2017 U.S. EPA evaluation, which urged ACHD to “expediently issue” the Title V permit to the company.

- The McConway & Torley foundry in the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh emits toxic metals such as manganese into the air of a densely populated portion of the city. Yet the facility went for two decades without being issued necessary air pollution permits, including five years, from 2010 to 2015, in which concentrations of manganese in the air outside the facility exceeded levels that the U.S. EPA believes to be of concern to public health.

- Allied Waste’s Imperial Landfill in Imperial, Pa., illustrates the potential of timely enforcement to protect public health. After students and staff at a nearby elementary school began complaining during the winter of 2008-09 of odors from the landfill causing “headaches, nausea, sinus issues, throat problems and ‘a feeling of being drugged,’” ACHD and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP) moved to monitor pollution at the site and took enforcement actions. Those actions led to the payment of significant penalties and required changes in how the facility handles waste to better protect public health, though air pollution concerns continue.

In recent years, ACHD has shown signs of a more aggressive approach toward air pollution at major industrial facilities.

- In 2017, ACHD issued a notice of violation to U.S. Steel for continued violations at the Edgar Thomson Plant. ACHD Director Dr. Karen Hacker called the action “a strategic change in ACHD’s enforcement efforts by utilizing all of our legal options, which in this case is a joint action with EPA.” The U.S. Justice Department is currently reviewing the enforcement action.

- In 2018, ACHD issued a notice of violation to Harsco and ATI requiring immediate action to control dust emissions from Harsco’s facility. ATI’s response to the enforcement action highlighted the shift in ACHD’s enforcement strategy: “ACHD has been investigating alleged fallout particulate emissions from the Natrona Facility for years,” the company complained. “Harsco and ATI have been cooperating in that investigation for years. The Order … is inconsistent with how ACHD has approached this matter in the past.” (emphasis added)

- In 2018 and 2019, ACHD took four enforcement actions against U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works, which eventually led to a proposed $2.7 million settlement that would require U.S. Steel to improve equipment and maintenance at the plant. In 2019, ACHD took a further step by joining a federal court lawsuit filed by citizen groups against U.S. Steel in response to the excessive pollution following the December 2018 fire at Clairton Coke Works.

To protect the health of Allegheny County residents, ACHD must fulfill its responsibility to enforce the law and hold air polluters accountable. Specifically, ACHD must:

- Issue timely, health-based permits – ACHD must eliminate the backlog of unissued Title V permits and ensure that renewals of existing Title V permits happen in a timely manner. Four facilities, including three profiled in this report (ATI Flat Rolled Products, Eastman Chemicals and Resins, and Harsco Metals) have never had a Title V permit, and six others (including Clairton Coke Works and Allied Waste’s Imperial Landfill) have Title V renewals that are past due as of May 2019. Issuing permits that protect public health, and doing so promptly, is critically important to build public confidence in ACHD’s commitment to clean air.

- Use timely, aggressive enforcement actions to hold polluters accountable – Historically, ACHD has relied on negotiated consent orders to resolve past violations of clean air rules and compel investments in emission control technology and improved practices at industrial facilities. While this approach may lead to constructive partnerships to cut pollution, in practice it has often led to repeated violations of the terms of consent orders by polluters, followed by yet more agreements destined to be violated. Any effective approach to enforcing environmental laws rests on the credible threat of financial penalties sufficient to eliminate any economic benefit from polluting along with tough requirements to ensure that polluters make necessary upgrades to protect public health. ACHD’s more vigorous recent approach to polluters such as U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works sends a message about the importance of compliance not only to U.S. Steel but also to all other industrial facilities in Allegheny County.

- Expand and improve air quality monitoring – As demonstrated by the recent action against U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works, data from air monitoring stations plays a critical role in identifying polluters that may be violating the law. Air monitoring in neighborhoods near industrial facilities, such as the fenceline monitoring near the McConway & Torley facility in Lawrenceville, can also help provide the public with assurance that pollution controls are working. Expanded monitoring, including support for citizen air pollution monitoring, and improved flow of information to and from the public, can help to improve enforcement and assure accountability.

- Partner with the public and other agencies to protect Allegheny County’s air – ACHD has partnered with citizens groups, the PA DEP, and the U.S. EPA to harness more resources to assist with enforcement. ACHD should continue those partnerships, and also create new tools to help the public understand and participate in the enforcement of air pollution laws.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

Lawn care goes electric

Who are the top climate polluters in the country?

The Biden administration has released $1 billion in funding for urban trees. Here’s why that matters.