Teach them how to say goodbye: Closing the door on the era of gasoline-powered cars

Saying goodbye to old technologies and ways of doing things is something we are going to need to practice over and over again in the coming decades as we address the climate crisis. To evoke the musical Hamilton, Massachusetts and California now stand ready to “teach us how to say goodbye” to the internal combustion engine - a technology that has become familiar, but is no longer compatible with a livable future.

Last fall, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that his state will require all cars sold as of 2035 to be zero-emission – in effect, electric. Just before the new year, the administration of Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker signaled it would follow suit as part of an overall plan to reduce carbon pollution.

Given the urgency of addressing global warming, does calling for a phase-out of the internal combustion engine 14 years in the future (a call that, by the way, mirrors our own recommendation in our 2020 Destination: Zero Carbon report) really meet the test of the moment?

To answer that question, it’s useful to ask another: What is it going to take to finally kick the internal combustion engine to the curb?

To start with, transitioning away from the internal combustion engine will require us to abandon or repurpose much of the globe-spanning infrastructure that enables oil drilled from the Saudi Arabian desert to power a car in Los Angeles or Boston. Ports, pipelines, refineries, gas stations – billions upon billions of dollars have been spent over the course of a century to build that stuff. And we will need to let it go … not an easy task when some of the wealthiest and most powerful corporations (and countries) on the planet have a clear financial interest in keeping the global fossil fuel machine going as long as they can.

Second, we’ll need to develop the infrastructure to enable a different transportation future – one powered by clean electricity (and, yes, a lot less driving). The good news is that the infrastructure to generate and deliver power across large regions of the country already exists in the form of the electric grid. But the grid will need investment to accommodate the unique needs of electric vehicles and to ensure that the energy delivered to those vehicles is clean and carbon-free. There will also need to be a lot more charging infrastructure to give people the confidence that EVs will get them where they need to go.

Lastly, there is the psychological challenge of divorcing ourselves from the internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle and everything it represents. This may be harder than we think, and it’s something that few people in the policy world talk about. Just think of the metaphors that the ICE has given us – rev your engine, shift gears, hit the gas pedal, run out of gas … the list goes on. Think of the memories – recollections of smells, sounds, people, experiences – wrapped up in vehicles as we have known them. For better and certainly for worse, the ICE has been a huge part of our lives for more than a century. To leave the familiarity of the rhythms of life with an ICE will take a significant mental adjustment for many of our fellow Americans.

Getting off the internal combustion engine is a tough job, in other words. Doing it in time to meet the climate crisis – especially given our failure to take adequate action on climate change over the last few decades – is even tougher.

Socio-technical transitions, it turns out, are complicated and multi-faceted. Frank Geels, a scholar who wrote about the transition from the horse and buggy to the automobile, wrote that “Societal functions are fulfilled by socio-technical systems, which consist of a cluster of aligned elements, e.g. artefacts, knowledge, user practices and markets, regulation, cultural meaning, infrastructure, maintenance networks and supply networks.” The switch from the ICE to the electric vehicle will require major changes across all of these dimensions.

And this is why the announcements by governors Newsom and Baker are so important. By putting a “sell-by” date on internal combustion engine cars, they have forced the residents of their states to envision what a future free from gasoline-powered vehicles will look like, and how best to get there.

That very act of envisioning a wholly different future can actually hasten its arrival. Oil is a capital-intensive industry – new oil fields don’t discover themselves, and even maintaining the existing network of oil infrastructure requires constant investment and maintenance. How much appetite will investors and oil companies have for ambitious capital investments if they suspect that the primary market for their product – cars – is drying up?

Oil companies are already reducing their capital investments as the world faces the real possibility of peak oil consumption. Every state or country that commits to transitioning to electric vehicles hastens the arrival of that peak. It’s not hard to imagine a downward spiral for oil as lack of investment in the fossil fuel industry makes the operation of gasoline-powered cars more expensive and less convenient. The arrival of that tipping point could make the transition to electric vehicles faster and more complete than anyone – even Baker and Newsom – might imagine possible.

Doubt that it can happen? Have a look at the speed with which the coal industry – which appeared invincible 10 years ago but has been increasingly starved of investment – tumbled into what now looks like terminal decline.

The declaration of the end of the ICE can also focus policy-makers, electric utilities and the public on the infrastructure investments needed to enable convenient charging of electric vehicles, as well as drive conversations about the ways in which vehicle electrification can accompany the transition to a less car-dependent transportation system. Those conversations will be difficult. There may be backlash. But phasing in the transition over a 10- to 15-year period of time helps to ensure that the transition does not create the kind of disruption that will drive politicians or the public to abandon the project entirely.

Physics demands that we get off oil as soon as possible – yesterday would have been good. But while 2035 may not be as soon as would be ideal, the step of setting a date – followed, one anticipates, by regulations that will make those commitments to an ICE phase-out real – is itself a powerful step. As California and Massachusetts plan their next steps – and are hopefully followed by other states – they can show the rest of the country that the transition away from gasoline-powered vehicles is possible.

Saying goodbye to old technologies and ways of doing things, and embracing new opportunities and tools, is something we are going to need to practice over and over again in the coming decades as we address the climate crisis. To evoke the musical Hamilton, Massachusetts and California now stand ready to “teach us how to say goodbye” to a technology that has become familiar to all of us, but that is no longer compatible with a livable future.

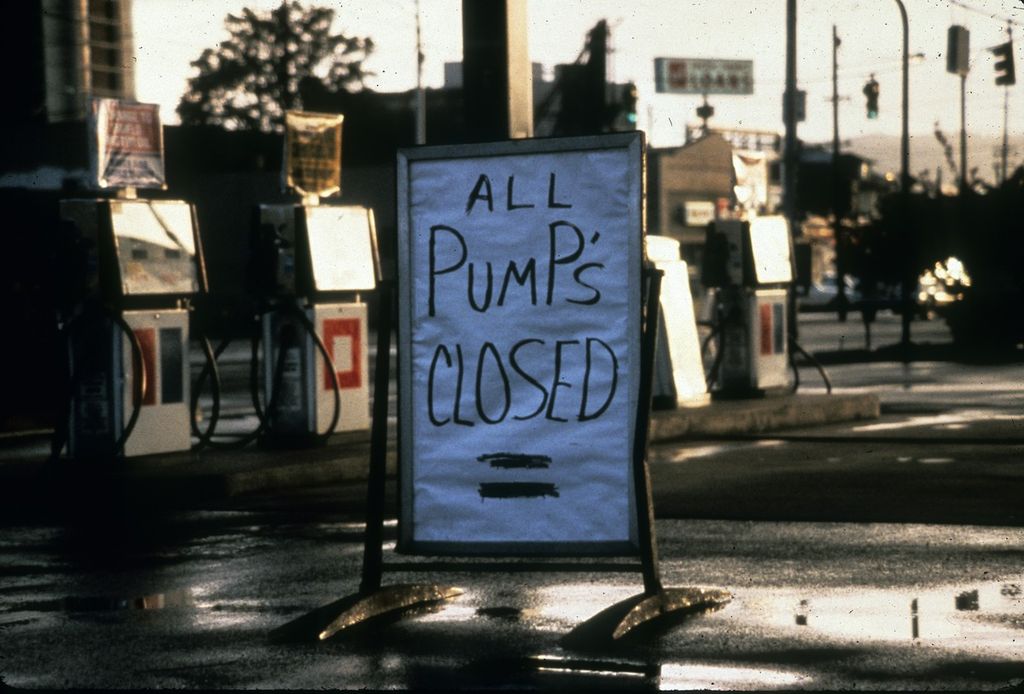

(Photo: Closed gas station in Seattle during 1970s energy crisis. Credit: Seattle City Archives, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

The million-mile battery and a clean energy future that’s built to last

Automakers could have learned to build EVs. They paid Tesla to do it instead.

The auto industry has a sustainability problem. And it’s not just about the environment.