Automakers could have learned to build EVs. They paid Tesla to do it instead.

Automakers have paid Tesla more than $8 billion to build the clean vehicles they didn't want to make. Now, with the transition to electric vehicles in full swing, that's looking like a bad bet.

Communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin is reputed (possibly erroneously) to have said that “the capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.”

Could some of today’s major automakers, in a quest to maximize near-term profits, wind up handing electric vehicle manufacturers like Tesla the tools that will ultimately bring about their own demise?

It’s possible. For more than 30 years, going back to California’s original adoption of the Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) program, it’s been clear that the future of the automobile is emission-free and, likely, electric. When that future might arrive has been open to question, but over those few decades a growing number of jurisdictions in the U.S. and abroad have followed California’s lead in setting steadily growing targets for EV sales.

Now, the electric future is here. In countries such as Norway, nearly all new light-duty vehicles being sold are battery-electric or plug-in hybrids. California smashed its goal of putting 1.5 million EVs on the road by 2025 two years early. More than 14 million plug-in vehicles will have been sold worldwide in 2023, an increase of more than one-third over 2022.

But a strange thing happened on the way to the EV transition. The names at the top of the global leaderboard for EV sales today are not names that would have been on anybody’s minds in 1990, or even 2010. Of the 10.7 million EVs sold worldwide in the first 10 months of 2023, 3.7 million – more than one-third – were made by just two manufacturers: China-based BYD and Tesla.

What’s noteworthy about BYD and Tesla is that they only make plug-in vehicles. BYD had been phasing out internal combustion engine-only vehicles for years and finally stopped making them altogether in 2022, focusing its lineup on electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. For Tesla, EVs have been the name of the game since day one.

Meanwhile, traditional automakers have struggled to ramp up their production of electric vehicles and to sell them once they are made. Electric vehicles are reportedly piling up on the lots of traditional car dealers in the U.S. (not counting Tesla, which doesn’t have dealers) as consumers refuse to pay the high prices automakers were counting on to attain profitability.

All of this raises the shocking possibility that one or more major traditional automakers will simply fail to make the leap to electric vehicles in time to preserve their relevance in a rapidly electrifying global market and, eventually, in the United States as well.

If that happens, automakers might look back at the 2010s as the period during which they sold an upstart competitor the tools that wound up bringing them down. While EV-focused manufacturers spent the decade preparing to win the future, some major automakers didn’t just continue cranking out wasteful and polluting (if profitable) gas-guzzling SUVs; they actually paid Tesla to build the EVs they did not want to make.

$8 billion in checks to Elon Musk

To understand how automakers’ choices in the 2010s led to their current predicament, we need to first talk about regulatory credits.

For decades, California and a number of other states (16 as of this writing) have set targets for the sale of advanced clean cars, including battery-electric vehicles, by large and intermediate auto manufacturers through the ZEV program. [1] The targets are commonly expressed as a percentage of sales, but compliance is demonstrated through the use of credits, which are distributed to manufacturers based on the characteristics of the vehicles they place for sale.

The credit scheme is complex and ever-changing, and the details don’t matter for this conversation, but there are two things that are worth knowing. The first is that selling pure electric vehicles generates a lot of credits. Regulators wanted to spur the adoption of EVs and designed the program to incentivize manufacturers to bring them to market.

The second is that credits are transferable – that is, companies that fail to meet their own targets can purchase credits from other manufacturers. The ZEV program isn’t the only such program that works this way – variations of credit trading exist at the federal level for compliance with greenhouse gas and fuel economy regulations, and in Europe and China – but it tells perhaps the clearest story of how automakers chose to respond to the challenge of vehicle electrification.

Some major automakers – Nissan and General Motors, in particular – made early commitments to building EVs that they hoped consumers might actually buy, with the Leaf and Bolt (now undergoing a major overhaul) remaining a steady presence on the electric vehicle scene.

But others chose not to make a serious commitment to EVs. Those automakers had two strategies available to them. The first was to manufacture “compliance cars” – vehicles intended only for the purpose of meeting a regulatory mandate, not generating widespread consumer interest. Former Fiat Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne went so far in 2014 as to ask consumers not to buy his Fiat electric car because the company lost money on every one they sold.

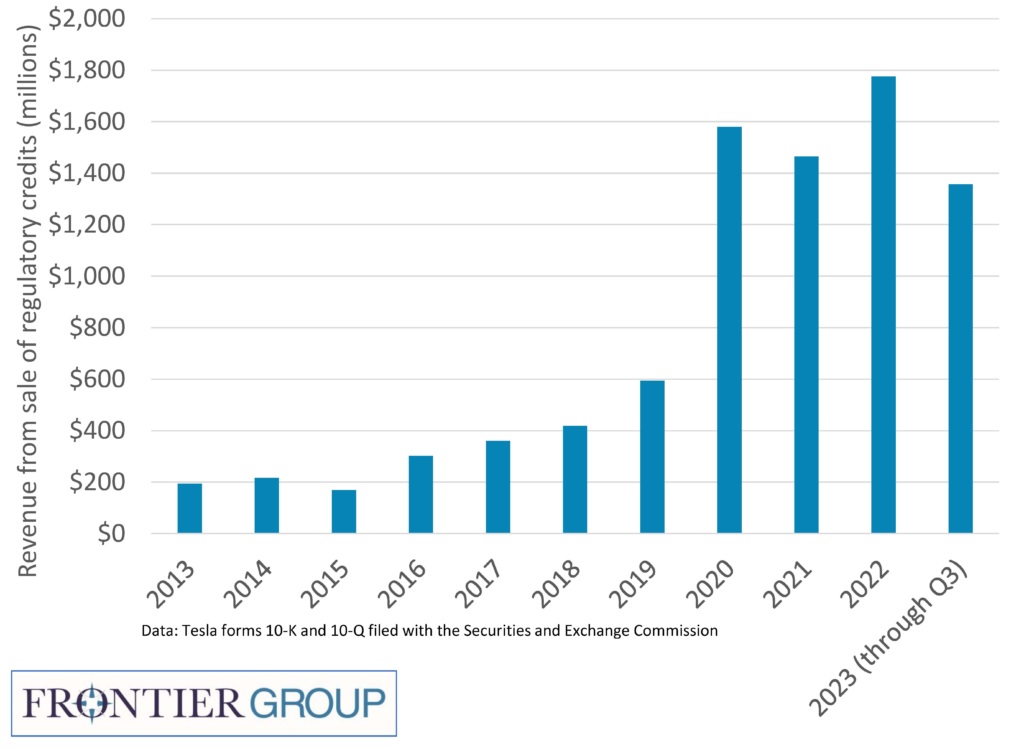

An alternative strategy was to simply buy credits from companies that were making EVs – including Tesla. Between credits used to comply with the ZEV program and other regulatory credit programs around the world, rival automakers have paid Tesla more than $8 billion for regulatory credits through the end of the third quarter of 2023, according to Tesla’s reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Stellantis, the company that absorbed Marchionne’s Fiat Chrysler, reportedly paid Tesla more than $2.4 billion for U.S. and European regulatory credits just between 2019 and 2021.

Figure 1. Tesla revenues from the sale of automotive regulatory credits

Automakers that chose to spend the 2010s writing checks to Tesla or making EVs they didn’t want consumers to buy might wish they had that decade back – and their current complaints about the speed of the EV transition need to be taken with that “lost decade” firmly in mind. As Tesla demonstrated, it is possible to make money selling electric vehicles that people want to buy – and not just expensive sports cars, but also everyday vehicles like the Model 3 and Model Y. Major automakers, with their capital and experience, could have followed a similar path. They opted not to.

And the path is likely to get even more difficult in the years to come. Regulatory requirements in California and the states that follow its lead are about to get dramatically tighter, as they must if the nation is going to meet its climate goals. The same is likely to be true at the federal level. That could mean even more big checks written to companies like Tesla (or others, such as the new EV-only startups hoping to follow Tesla’s lead or perhaps even legacy automakers like Hyundai-Kia that can crack the code on making and selling EVs), as well as big fines paid to the federal government, with Ford estimating that President Biden’s proposed new fuel economy standards will cost it $1 billion in fines through 2032.

The rise of cheap Chinese EVs puts further pressure on the global competitiveness of all automakers, especially the American “Big Three” of General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, which increasingly find themselves on the outside of the global car market looking in. In the early 2000s, the Big Three ranked first, second and fifth in global vehicle sales. Today, only Stellantis remains in the top five. General Motors ranks sixth. Ford ranks seventh. And just a bit further down the list, and rising quickly, is BYD in 10th, with Tesla in 14th.

In short, traditional automakers – and not just American ones – find themselves between a rock and a hard place, confronted with stronger regulations to drive electrification, struggling to make profitable and affordable EVs that people want to buy, and forced to adapt to a technological landscape – most notably in charging – that not only did Tesla design and build, but the automakers actually paid it to build. They made bad choices and are now experiencing the consequences.

The temptation for major automakers to kick the can even further down the road – to fight for regulatory rollbacks that allow for one more hit of profits selling gas-guzzling SUVs before the inevitable crash – will be strong. But a refusal to face up to the future and a penchant for taking the easy way out is what got the auto industry into its current mess.

Time is running short to reduce climate pollution from transportation in the U.S. and around the world. And time is similarly running short for automakers to position themselves to make and sell their products in a carbon-constrained world. For more than three decades, the companies with the know-how and resources to lead the world into that transition have instead rolled over and hit the snooze button on electrification.

Now, with climate alarm bells ringing louder than ever, automakers that want to continue to sell cars in the future need to get out of bed, put on a pot of coffee, and get to work figuring out how to do it as sustainably as possible.

Or they can get out of the way and let someone else try.

[1] California is empowered under the federal Clean Air Act to adopt its own more stringent automobile emission standards, including the ZEV program. Other states with air pollution problems can choose to adopt California’s standards or federal standards.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

The million-mile battery and a clean energy future that’s built to last

The auto industry has a sustainability problem. And it’s not just about the environment.

Totally wired: How Quebec became a leader in electric vehicle charging