Travis Madsen

Policy Analyst

In December 2004, Chicago-based Exelon Corporation announced plans to acquire Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), the last remaining New Jersey-based energy company that hasn’t been taken over by a large out-of-state corporation. Consolidation of Power analyzes the risks this deal poses to consumers in New Jersey’s deregulated electricity market—who depend upon vigorous competition between energy suppliers to get a fair deal for reliable service.

On February 4, 2005, Chicago-based Exelon Corporation requested formal permission from New Jersey regulators to acquire Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), the last remaining New Jersey-based energy company that hasn’t been taken over by a large out-of-state corporation.

As the voice of New Jersey’s electricity consumers, the state Board of Public Utilities should reject Exelon’s proposal. The takeover would increase the monopolistic tendencies of the electricity market, threaten the reliability of electric service, increase risks to public safety, and reduce the ability of state regulators to defend the interests of electricity customers in New Jersey, leading to higher costs and poorer service.

The takeover would increase Exelon’s market power.

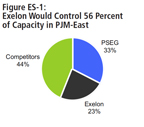

• If approved, the takeover would create the largest electric utility company in the country, with $79 billion in assets, 9 million customer accounts and business operations in electricity generation, distribution and marketing, plus natural gas supply and delivery. The new Exelon would:

• Because of its large size and wide scope, the decisions of the company would be extremely influential in determining the nature, quality, and price of electric service for customers across New Jersey, the Mid-Atlantic and the Midwest.

The takeover could threaten the viability of New Jersey’s electricity auction, potentially leading to higher rates.

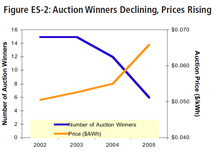

• New Jersey depends on vigorous competition between electricity suppliers at a bulk auction to hold down electricity rates. However, the number of winners at the auction has declined almost two-thirds in the last two years, from 15 to six corporations. At the same time, the fixed price for electricity resulting from the auction has risen 19 percent. (See Figure ES-2).

• While other factors, including fuel costs, account for part of the cost increase, the percentage of supply contracts going to a single bidder has risen as well. In the PSE&G service territory, the maximum number of bids won by a single bidder increased from 21 percent in 2002 to 36 percent in 2004. This pattern follows a national trend of declining numbers of participants able to compete in the electricity market in a meaningful way.

• PSEG officials have stated publicly that PSEG has provided, directly or indirectly, at least 75 percent of the electricity supply at the auction.

• Further reducing the number of competitors would make New Jersey’s market look more like the dysfunctional power markets in some Midwestern states. For example:

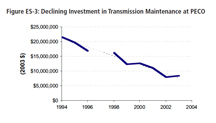

Exelon’s cost-cutting measures could harm the reliability of New Jersey’s electricity system and quality of service to consumers.

• Large holding companies like Exelon have a history of making cuts that lead to reduced reliability of the electricity system, driven by pressure to reduce costs in order to deliver larger returns to shareholders.

• Compared to PSEG, Exelon has a poor reliability and customer service record.

Exelon is basing much of its business strategy on increasing the output of nuclear power plants, potentially risking public safety.

• Exelon is often praised by investor analysts for what is known as “The Exelon Way,” a system of operating nuclear power plants at higher rates of output, thus earning higher rates of return for shareholders. However, that additional productivity comes at great risk to public safety:

New Jersey regulators would lose the power to protect consumers from risky investment decisions.

• State regulators would lose the authority to protect consumers from risky non-utility business ventures. These ventures can put pressure on a company’s credit rating and lead to higher interest rates—which are then passed on to New Jersey families and businesses.

Concessions will not solve the longterm problems inherent with the proposed takeover.

In order to win regulatory approval of its plan, Exelon is likely to propose deals or make concessions to federal and state regulators. Exelon has already revealed a proposal to divest a small amount of its assets to competitors and claimed that the economic efficiencies created by the deal will benefit consumers.

However, the proposed concessions would only sugarcoat the deeply rooted anti-competitive and anti-consumer problems inherent in the merger:

• Exelon’s proposed divestiture is far too small to mitigate the market power it will gain or the imbalance it will cause in the New Jersey and PJM wholesale energy markets. Exelon’s claims that the plan will eliminate market power concerns are based on:

• In addition, Exelon has not formally proposed sharing any of the economic efficiencies it expects to create with ratepayers.

New Jersey regulators should reject Exelon’s proposal.

Exelon’s takeover of PSEG can only proceed with approval from the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU). The BPU should reject the proposal on the grounds that it does not serve the public interest—and in fact could reduce competition, raise rates, reduce reliability and risk public safety.

Such a decision would not be without precedent. In the past year, Arizona and Oregon utility regulators stopped out-of-state businesses from buying state-based energy companies because the deals did not provide any public benefit.

Similar action is warranted in this case. President Fox and the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities Commissioners should defend the interests of New Jersey’s electricity consumers and reject Exelon’s takeover of PSEG.

Policy Analyst