While supplies last! How marketers turned the humble reusable cup into a status symbol

Stanley Quenchers seem like a product environmentalists should sing praises for. But even sustainable products can be twisted by consumer culture and subsumed into the growth paradigm.

Part One: The Stanley Quencher story

In January 2024, Saturday Night Live ran a sketch called “Big Dumb Cups” that poked fun at Stanley Quenchers and the well-hydrated shoppers who obsess over getting their hands on them. If you’re not familiar with the cup that’s taking over the water bottle market, here’s a brief summary:

- Stanley was projected to make $750 million in revenue in 2023, a tenfold increase from $70 million just four years earlier, mostly thanks to their smash hit Quenchers.

- Target’s limited-run “Galentines Day” collection, released in January 2024, spurred hordes of shoppers to wait in line overnight, caused stampedes at several stores, and sold out in less than four minutes according to one customer.

- The cups are so coveted that Target fired multiple employees for purchasing cups for themselves, violating a policy that prohibits employees from using their status “to gain an unfair advantage over guests when it comes to purchasing merchandise.”

- Limited edition Stanleys can be resold online for hundreds of dollars. As of this writing, the average price of Stanley x Starbucks 40oz Winter Pink tumblers resold on StockX is $186, while the Stanley x Lainey Wilson Watermelon Moonshine 40oz tumblers sell for $215 on average.

The success of Stanley Quenchers can be primarily attributed to the marketing strategy implemented by Stanley’s new president, Terence Reilly, who joined the company in 2020 after making clogs cool again at his previous gig with Crocs. Leveraging an endorsement of the product from a commerce blog called The Buy Guide, Reilly was able to start building buzz among influencers which spilled over into viral momentum on TikTok.

Stanley tumblers are especially popular among women and tweens. They were the most popular Christmas gift among Gen Z TikTok influencers in 2023. Middle-schoolers have been bullied for carrying knockoff Stanleys, while other students have reported a boost in popularity for donning the real thing. With hundreds of colors available, many consumers assemble a large collection, allowing them to pick the Stanley that best fits their outfit for the day. Chelsea Espejo, a Stanley Quencher collector, told CNBC, “They’re actually part of my personality. If I don’t have [my Stanley], if I don’t choose the right color, my day kind of doesn’t go how I planned it.”

Stanley cups are not particularly innovative, and they’re not a perfect product. In 2019, prior to Reilly’s marketing wizardry, the Quenchers were actually discontinued due to poor sales. A quick look at negative reviews for Quenchers on Stanley’s website shows that many people have been disappointed by the quality of the cups and Stanley’s customer service for the price they paid (e.g., they leak, they chip, slow customer service). Stanley is now facing multiple lawsuits for failing to disclose the presence of lead in their cups.

Stanley says built for life but really its not and their guarantee does not cover everything. I have two Stanley cups and both the paint is chipping away. Reached out to Stanley says they do not cover it. I would think for the cost it would hold up. Others have said the same. Very disappointed in the product and their guarantee policy. Shame on you Stanley your products are no longer worth the money. [sic]

-Donna J, top negative comment from Stanley’s website

I don’t own a Stanley cup, and for the record, I think it is probably a quality product. But all things considered, it’s safe to say that Stanley quenchers aren’t popular solely because of their excellence as a utilitarian product; they are also valued as a trendy fashion accessory. They are big, bright, colorful, and above all, conspicuous.

Part Two: Keeping up with the Joneses

In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Thorstein Veblen introduced the theory of conspicuous consumption. With the emergence of a “nouveau riche” (new rich), or leisure class, Veblen argued that a “predatory culture” finds new ways to make class distinctions, including through the consumption of luxury goods. Veblen writes, “Since the consumption of these more excellent goods is an evidence of wealth, it becomes honorific; and conversely, the failure to consume in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority and demerit.”

In a society where our economic output (and hence, our income) measures our individual contributions to society’s collective goal of growing the pie, conspicuous consumption elevates our social standing. Conspicuous consumption is possible because of the presence of a thriving leisure class with disposable income and spare time to spend on luxury goods.

This theory helps explain the cup craze within our current paradigm. Put simply, we want the cups because they are a highly visible signal of our wealth and thereby increase our social status. This point is supported by the flashy design of the cups and their massive size. They are hard to miss and immediately recognizable as an expensive, hard-to-obtain item. The influencers at The Buy Guide and on TikTok helped cultivate the cup’s social value.

High fashion, luxury cars, and lavish homes are all examples of conspicuous consumption in action (notice these apropos examples also happen to be very harmful to the environment). This type of consumption is excessive and unnecessary because people consume more than they need, or even want, in order to keep up with the Joneses. Nobody waits in line overnight or pays way too much for a cup just to obtain a quality drinking receptacle. They do it because other people in their social circles will see them drinking out of a Stanley cup, and say, “Hey, cool Stanley!”

Part Three: While supplies last!

Conspicuous consumption isn’t the only socio-economic marketing tool Reilly has wielded with expert precision to drive demand for Stanley Quenchers. While Stanley claims they are working on manufacturing as much product as possible, they also “want a little bit of scarcity.” By dropping limited edition cups, Stanley increases demand for them. The scarcity of limited edition colors and celebrity collaborations heightens consumers’ desire to rush to get theirs… while supplies last!

To explain how scarcity increases the demand for cups, we need to take a quick detour to the realms of classical economics and marketing psychology.

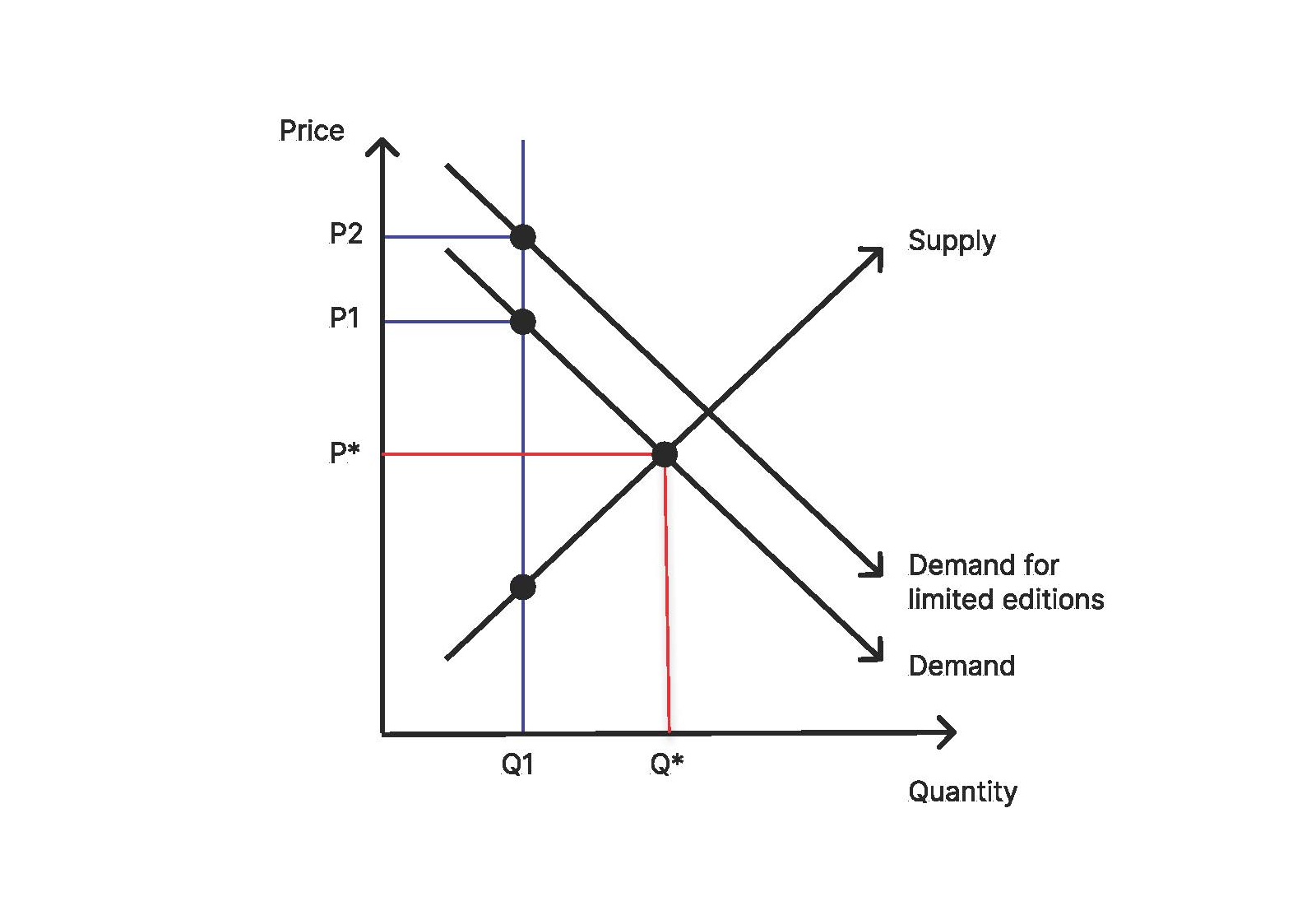

In a free market with dynamic pricing, the price and quantity of a good are determined by the forces of supply and demand. Supply and price have a direct relationship to each other, while demand and price have a negative relationship. Under the assumptions of this model, when demand exceeds supply (i.e., cups are scarce), cup producers would increase the quantity of cups on the market to take advantage of high prices and high demand, bringing down the price until supply equals demand. But if the supply of cups is restricted for any reason, demand stays higher than supply and cups become scarce. The price stays above the equilibrium price, creating a deadweight loss for consumers. This loss is borne by consumers who are locked out because they can’t afford the higher price (Figure 1).

Figure 1: At Q1, demand is higher than supply. In a free market, producers would react to the high price and demand by supplying more cups. If the quantity is fixed at Q1, however, demand stays higher than supply and the price stays at P1.

In his book Influence: the Psychology of Persuasion, marketing psychologist Robert Cialdini identified a psychological response to scarcity that’s now known as the scarcity principle. In short, “Opportunities seem more valuable to us when their availability is limited.” Returning to our economic model, scarcity increases the demand for cups, moving the entire demand curve to the right and increasing prices further (Figure 2). Therefore, two factors inflate the price of scarce goods: the low supply of the product, which keeps the price above equilibrium, and the resulting scarcity, which increases demand.

Figure 2: According to the scarcity principle, fixing the quantity of cups at Q1 increases demand for the product. As demand increases at a given quantity, so does the price.

The scarcity principle also plays out in sneaker culture, wherein sneakerheads spend hundreds, even thousands, of dollars purchasing shoes they are culturally forbidden from wearing. Scarcity transforms the object from a utilitarian good into a collectible, dissociating its value from its usefulness and subjecting it to speculative markets. The artificially high price creates deadweight loss for consumers who can’t afford the higher price and opens the door to irrational exuberance, which creates economic bubbles that harm consumers. The scarcity principle can also lead to price gouging if the scarce good is a staple like toilet paper or Taylor Swift tickets.

Manufacturers and their marketing teams take advantage of the scarcity principle by positioning themselves as the only legitimate producer of a limited edition product. With a highly distinctive brand and product, they can create a new market where they have monopoly control over the quantity supplied. The absurdity of this situation is that we are living in a post-scarcity world. Quality water bottles aren’t scarce, nor are Stanleys. What is scarce is that Stanley, that one color that only a select few diehards will get to own. Under post-scarcity conditions, we are seeing companies perniciously find ever more inventive ways to create perceived scarcity.

In the case of Stanleys, the scarcity principle and conspicuous consumption appear to be working in concert, each reinforcing the other to create a situation where a sustainable product is being consumed in unsustainable and unhealthy ways.

Part Four: Reclaiming sustainable products in the name of sustainability

This is why we can’t have nice things (in our current paradigm). What began as a sustainable product that was designed to last a lifetime, turned into a viral TikTok trend, then became a fashion accessory, then became a symbol of social status, then became a collectible item subject to stampedes and speculative investing.

At first glance, Stanley Quenchers seem like a product environmentalists should sing praises for. It’s a reusable cup that reduces waste from single-use plastics and is built to last a lifetime. But even sustainable products can be twisted by consumer culture and subsumed into the growth paradigm. The harms of this cup market – kids being bullied for being less affluent than their peers, employees losing their jobs for buying a cup, social engineering and targeted advertising, spending too much on an artificially over-priced good, the ironic wastefulness of one person owning 47 (and counting) reusable cups, the environmental cost of producing all this excess – outweigh the utilitarian benefit derived by drinking from our Stanley cups.

The Stanley cup craze is evidence that we are living in an age of great abundance and even greater absurdity. If we don’t break away from this paradigm, even the products that we think of as “quality,” “green” and “sustainable” will continue to contribute to the unsustainable exploitation of earth’s resources. For example, we will all probably be driving electric vehicles in 30 years, but in our current paradigm, we will still be constantly pressured to buy a new one, another one, or a bigger one.

The Stanley cup craze has reached its peak, according to one consumer trends analyst, but if the social and economic forces that caused it aren’t upended, another viral craze will take its place. This post isn’t going to bust the paradigm, but it highlights some ways we can start.

As environmentalists, we can’t play into the commercialization of sustainable products lest they become part of the problem (e.g., EVs are cheaper to own and more fun to drive than gas-powered cars these days). Instead, we need to uphold the principles underlying the need for sustainable products (e.g., To live sustainably and preserve the planet for future generations, we need to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by greening the electric grid, transitioning to electric cars, moving away from a culture of private vehicle ownership, and building more walkable and bikeable communities).

As consumers, we can’t keep falling for clever marketing schemes. We can and should control our own consumptive behaviors. We can drive our ugly Nissan Leafs into the ground even though the neighbors proudly have a new Tesla featured in their driveway. When we see a news story about people waiting overnight in long lines for a cup, we can ask ourselves who the real sucker is, as we defiantly drink ice-cold water from our perfectly fine knockoffs. And we can teach our kids what’s really cool and important: experiences, connections and relationships; wildlife and nature; and sure, practical products that are designed to last.

As organizers, we need to engage people in policy fights, such as data privacy and truth in advertising, that lead them to question the dominant paradigm and open their minds to something new.

P.S. Please do not be offended, dear reader, if you are a proud Stanley cup carrier. I’ll reiterate that your Stanley is probably a pretty darn good cup.

Topics

Authors

Quentin Good

Quentin has a B.A in Economics from Metropolitan State University of Denver and an M.A in International Finance, Trade, and Economic Integration from the University of Denver. He served with the U.S. Peace Corps for 3 years in Senegal, West Africa, as a community economic development volunteer and sector leader. Quentin lives in Denver, Colorado, and enjoys playing guitar, skateboarding and spending time with his dog Cooper.

Find Out More

Too much of a good thing? The environmental downside of the “Stanley cup” craze.

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

Consumerism harms us and the environment. These communities prove we can do better.