MBTA Riders Are Holding Up Their End of the Bargain

Over the last decade and a half, one major source of T revenue has actually grown at a faster rate than operating expenses: transit fares.

How will we know when the MBTA is fiscally back on track?

In its annual report to the Legislature (PDF), released in December, Governor Charlie Baker’s Fiscal and Management Control Board (FMCB) proposed a standard: “The FMCB calls for annual growth rate in MBTA operating expenses to align with the annual rate of revenue growth,” the board stated.

Over the last decade and a half, one major source of T revenue has actually grown at a faster rate than operating expenses: transit fares.

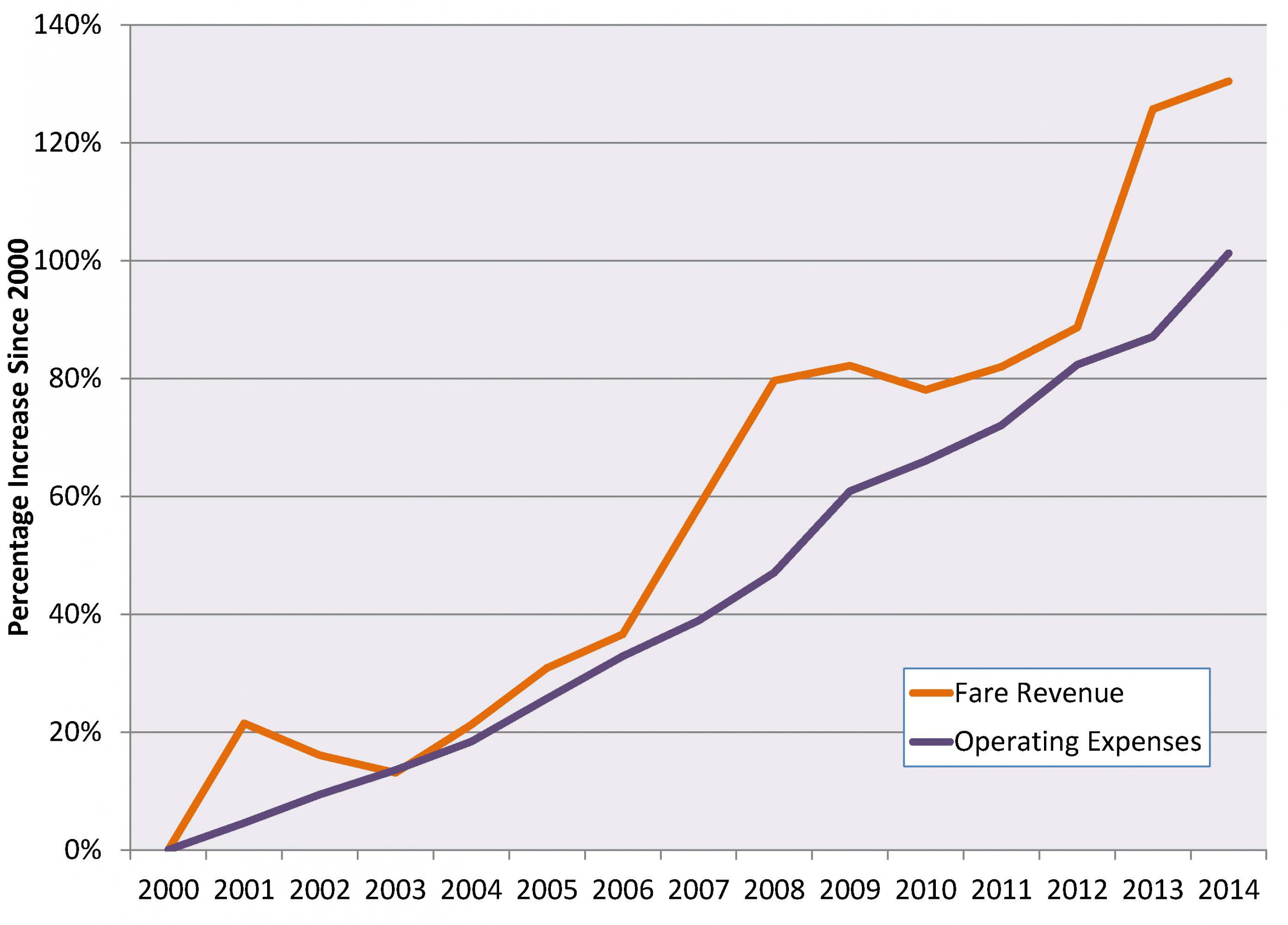

Let’s look at the numbers. Between 2000 and 2014, according to the National Transit Database, the MBTA’s operating expenses increased by 101 percent in nominal terms, jumping from $711 million to $1.43 billion. Over that same period of time, annual fare revenue increased by 130 percent, from $250 million to $577 million.

During this period, fare revenue increased at an annual rate of 6.1 percent, while operating expenses increased at a slower rate of 5.1 percent.

Rate of Change in Fare Revenue and Operating Expenses, 2000-2014[1]

MBTA riders, in other words, have upheld their end of the bargain. As we detailed in a blog post back in April 2015, when comparing the MBTA fairly against other agencies, T riders cover about the same share of the system’s expenses as transit riders nationwide.

MBTA riders are not the source of the system’s current woes. MBTA riders weren’t responsible for the debacle of Forward Funding, initiated in 2000, which intended to put the T on a fixed budget tied to state sales tax revenues. The result, as described by the must-read 2009 report, Born Broke, was a disaster. Sales tax revenue, which was anticipated to rise by 3 percent per year, never lived up to expectations, the T proved unable to absorb the Big Dig debt that was shifted onto its books, and the agency launched into a lost decade of deferred maintenance, disruptive fare hikes, and financial chicanery in an effort to balance the books.

It is not the fault of T riders that lawmakers took so long to address the system’s structural flaws before enacting transportation reforms in 2009 and 2013 – the latter of which finally set the wheels in motion for addressing long-standing capital needs such as the purchase of new Red and Orange Line cars, and provided the additional infusion of state assistance for the T that the Baker administration now rejects.

Nor is it the fault of MBTA riders that they are forced to ride in overcrowded trains and buses in an unreliable system – at the same time that Boston’s historic building and jobs boom is creating intense new demand for transit.

There are solutions to the T’s fiscal challenges. Improving the efficiency with which the MBTA provides service (as the Control Board is working hard to do), relieving the T of Big Dig debt, delivering on earlier state promises of financial support, and making smart capital investments to reduce operating costs and improve service quality can all help put the agency on a sound fiscal footing for the future. Predictable, modest increases in fares have an important role to play as well, as the 2013 transportation reform law recognized.

Over and over again, over the past decade, the MBTA has turned to riders for more funding, and they have delivered. Turning to riders for large fare hikes as a major source of new revenue now, before the MBTA gets its own house in order, is not likely to sit well with riders. Nor should it.

[1] Data: National Transit Database

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.