Slaughterhouses Are Polluting Our Waterways

Industrial livestock and poultry slaughtering and processing plants ("slaughterhouses") dump huge volumes of pollution into America’s rivers, threatening our health and harming our environment. Despite Clean Water Act requirements, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has not updated decades-old pollution standards to protect the public.

Industrial livestock and poultry slaughtering and processing plants (“slaughterhouses”) dump huge volumes of pollution into America’s rivers, threatening our health and harming our environment. Despite Clean Water Act requirements, the EPA has not updated decades-old pollution standards to protect the public.

Slaughterhouses are major water polluters

Slaughterhouses – industrial facilities that process and package poultry, beef, pork and other animal products – discharge millions of pounds of pollution into America’s waterways every year. These processing facilities are a leading source of water pollution.

- Wastewater from slaughterhouses contains high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to toxic algal outbreaks and dead zones in waterways such as the Gulf of Mexico.

- In 2019, slaughterhouses released more than 28 million pounds of nitrogen and phosphorus directly into the nation’s rivers and streams.

- Meat and poultry processing facilities are the largest industrial point source of nitrogen pollution discharged to waterways, according to 2015 EPA data. They also release 14% of the phosphorus released into waterways from industrial sources.

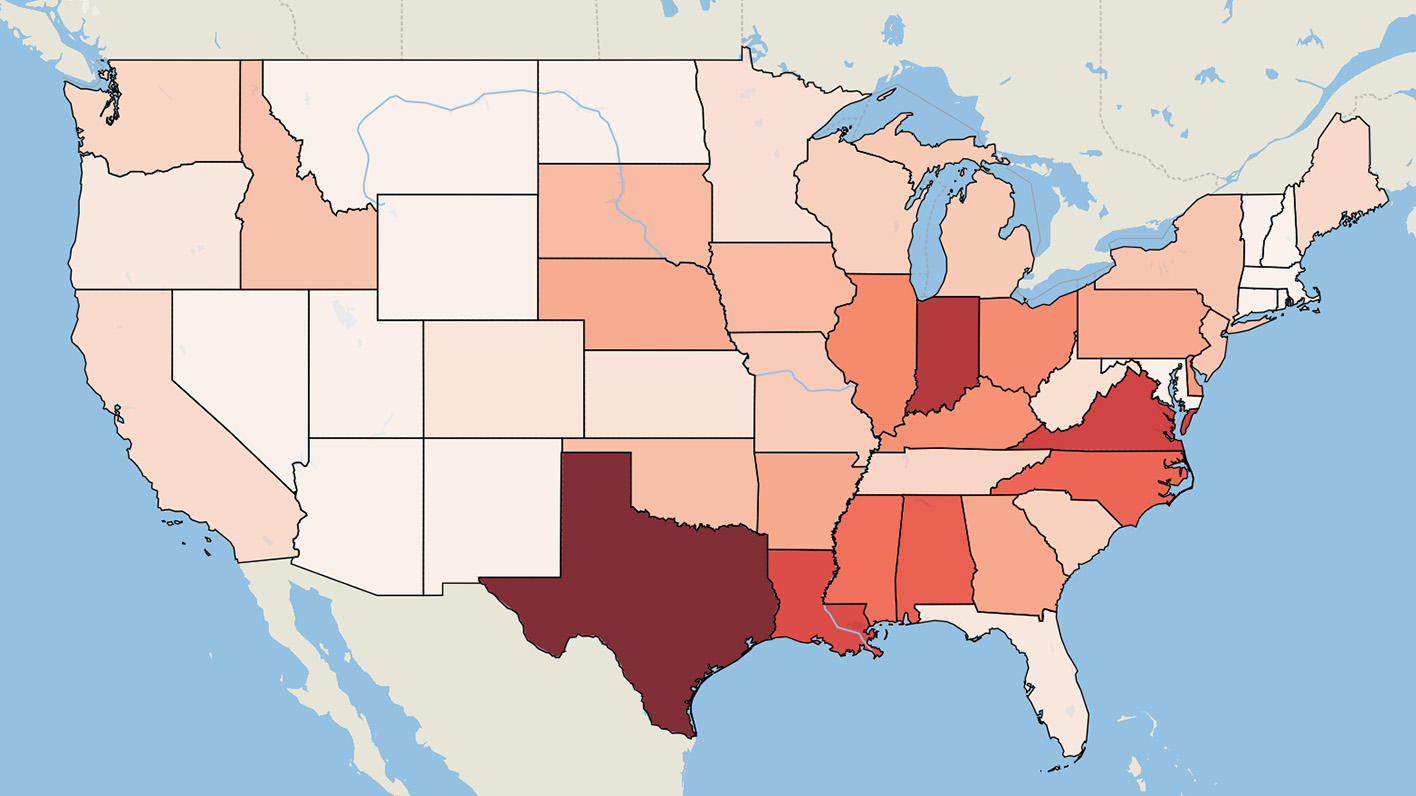

How to use this map to learn about slaughterhouse pollution

You can view the location of large slaughterhouses across the country, as well as smaller slaughterhouses and other facilities such as rendering plants for which 2019 water pollution data was available from EPA’s Water Pollution Loading Tool or Toxics Release Inventory.

These 219 facilities discharge pollution directly into waterways. Clicking on any slaughterhouse will display a text box with details about available data, such as how many animals it processes annually, the name of the local watershed or how much nitrogen and phosphorus pollution the facility released to surface waters in 2019. Many of these facilities released additional pollution that is not included in the total pounds shown (to avoid possible double-counting).

These 219 facilities discharge pollution directly into waterways. Clicking on any slaughterhouse will display a text box with details about available data, such as how many animals it processes annually, the name of the local watershed or how much nitrogen and phosphorus pollution the facility released to surface waters in 2019. Many of these facilities released additional pollution that is not included in the total pounds shown (to avoid possible double-counting).

While these 163 facilities do not dump waste directly into local waters, they may pose several other pollution risks – including sending their waste to sewage treatment plants that then discharge into waterways, spreading pollution on land where it may run off into nearby streams and rivers, or by attracting or sustaining highly polluting factory farms to a watershed.

While these 163 facilities do not dump waste directly into local waters, they may pose several other pollution risks – including sending their waste to sewage treatment plants that then discharge into waterways, spreading pollution on land where it may run off into nearby streams and rivers, or by attracting or sustaining highly polluting factory farms to a watershed.

To see how slaughterhouses may put your local waterways at risk, zoom in and click on a watershed. Clicking on a specific watershed will show a text box with details about the number of large facilities located there and/or facilities that report water pollution, along with the pounds of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution reported in that watershed. The greater the number of slaughterhouses in a watershed, the greater the likelihood of cumulative damage to local waterways there.

Where the data in this map comes from

This map contains information about large poultry, beef and pork slaughterhouses, obtained from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). It also displays water pollution information for slaughtering and processing facilities for which the EPA has data. Many facilities in the USDA database do not report any direct pollution to waterways, and some facilities included in the EPA data, such as rendering plants, do not appear in the USDA database. For more details, please see the methodology below.

The U.S. EPA has the power to reduce pollution from livestock and poultry slaughter and processing facilities

The federal Clean Water Act requires the EPA to set pollution control standards for each type of industry – including slaughterhouses – and to update those standards as advances in pollution-control technology allow. Yet the agency last updated pollution standards for the largest slaughterhouses in 2004, while other slaughterhouses are only required to meet federal standards set 44 years ago.

Updated pollution standards could lead to significantly cleaner water in areas where slaughterhouses are concentrated. The most technologically advanced slaughterhouses already release far less pollution than the dirtiest plants.

For more information about water pollution from slaughterhouses, see our factsheet: Slaughterhouses Are Polluting Our Waterways. Additional information is available about Environment America’s work on clean water, and Environmental Integrity Project’s research on slaughterhouse pollution. This map was made possible in part by support from the Clean Water for All coalition.

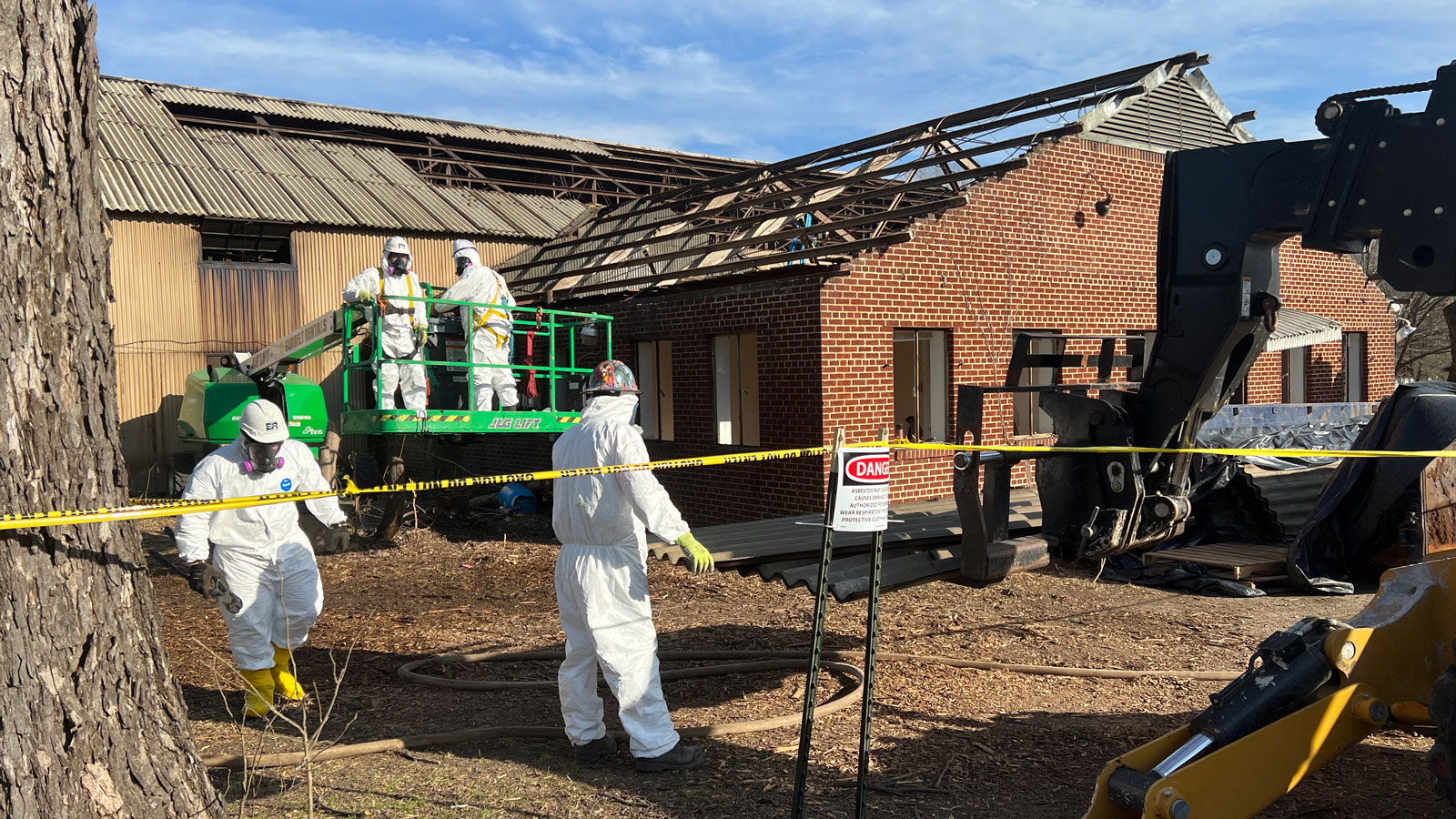

Photo credits: Slaughterhouse: Watershed Post via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.; Waste lagoon: Bob Nichols, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, public domain.

Tell EPA: Stop Slaughterhouse Pollution

Methodology

This map combines information about slaughterhouses from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) with pollution data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Data about the types of livestock and poultry processed at each facility, and the estimated volume of animals slaughtered and/or processed comes from USDA, Dataset: Establishment Demographic Data (MPI Directory Supplement), 10 May 2021 release. Geographic coordinates for each facility were downloaded from the map at USDA’s Meat, Poultry and Egg Product Inspection Directory website on 13 May 2021.

Pollution data was downloaded from two EPA sources on 15 May 2021. Data on facilities with a primary North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code of 3116 or with a Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code of 2011, 2013, 2015 or 2077 that reported releases to surface water in 2019 were downloaded from EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI). Calculated loadings based on Discharge Monitoring Reports (DMR) in 2019 for nitrogen, organic enrichment, phosphorus and solids from facilities with a primary NAICS code of 3116 or a SIC code of 2011, 2013, 2015 or 2077 were downloaded from EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online database using the Water Pollutant Loading Tool.

Facilities are included in the map if they meet one or more of these criteria:

-

Beef or pork facility that USDA lists with a “slaughter volume category” of “4” (the highest category for these facilities), meaning it handles 100,000 to 10 million animals per year, or chicken or turkey facility that USDA lists with a “slaughter volume category” of “5,” meaning it handles 10 million or more animals per year.

-

Reported a direct discharge to surface waters in the downloaded TRI data.

-

Appeared in the downloaded Water Pollutant Loading Tool data with non-zero levels of pollution.

We excluded egg processing facilities that we believe appeared erroneously with a NAICS code of 3116 or a SIC code of 2115.

To pair the USDA facility information with facilities for which EPA had water pollution data, all facilities were mapped in QGIS. A nearest neighbor analysis showed the proximity of each facility from the USDA data to a facility in EPA’s data. Facilities were checked for matching facility names, street addresses or other confirmation of a match before pairing facility information with water pollution data. A number of facilities listed in the USDA data did not have a corresponding entry in EPA pollution data because they do not report any discharges to water that appear in the EPA database.

A number of facilities that appear in the EPA data do not appear on the USDA facility list at all, likely because they are rendering or waste facilities that deal with byproducts or with fish, and are not regulated by USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service.

When water pollution information for a facility appeared in both the TRI and Water Pollutant Loading Tool data, the Water Pollutant Loading Tool data was used. We made one exception for a Pilgrim’s Pride facility in Enterprise, Alabama, where the pollution levels listed in the Water Pollutant Loading Tool were improbably high, and we chose to use the TRI information. We retained pollution information for eight facilities where EPA flagged that the data may contain potential outliers. Nitrogen and phosphorus water pollution was aggregated for each facility for which data was available from the Water Pollutant Loading Tool. Nitrate compound information is presented for facilities for which data came from TRI. Amounts of other pollutants were not aggregated to avoid potential double-counting.

Watershed information was obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Map Downloader on 7 July 2021. Watersheds are displayed at the 4-digit hydrologic unit code (HUC) level, and “local watershed” information in facility popups refers to 12-digit HUCs. For those facilities that did not have watershed information contained in their original data, associated watersheds were determined using QGIS mapping software. Nitrogen, phosphorus and nitrate compound pollution were then aggregated by watershed for facilities with available pollution data.

The USGS Watershed Boundary Dataset displayed on the map has been simplified in order to speed page load times. As result, for some facilities – such as Ferdinand Processing in Indiana, and Pilgrim’s Pride Corporation and Mar-Jac Poultry in Gainesville, Georgia – the facility’s actual watershed differs from the watershed in which the facility appears on the map. When assigning watersheds to facilities that did not have EPA-provided watershed information, original full resolution watershed boundaries were used.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Gideon Weissman

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Find Out More

Superfund Back on Track

Safe for Swimming?

The Threat of “Forever Chemicals”