From Pollution to Solutions

Maximizing Clean Energy Progress from State Carbon-Pricing Investments

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), created more than a decade ago by Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states, has contributed to the 60 percent reduction in carbon pollution from power plants in those states since 2005, while fueling the transition to a clean energy future.

Smart investments in clean energy programs have been critical to the program’s success. With the nine current RGGI states having recently tightened the program’s limits on power plant pollution, and with New Jersey and Virginia aligning themselves with RGGI, it is important that the region invest revenue from the program in ways that move as quickly as possible toward a clean energy future.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), created more than a decade ago by Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states, has been a clear success. The program has contributed to the 60 percent reduction in carbon pollution from power plants in those states since 2005, while fueling the transition to a clean energy future.

Smart investments in clean energy programs have been critical to the program’s success. With the nine current RGGI states having recently tightened the program’s limits on power plant pollution, and with New Jersey and Virginia aligning themselves with RGGI, it is important that the region invest revenue from the program in ways that move as quickly as possible toward a clean energy future.

Smart clean energy investments can make a big difference. Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states saved 4.4 million megawatt-hours of electricity and cut global warming pollution by 2.4 million tons with their clean energy investments from 2009 through 2016.[i] If New Jersey were to rejoin RGGI, adopt a strong cap on power plant emissions, and follow the example of leading states by investing revenues from carbon pricing in clean energy, its investments from 2020 through 2030 could save nearly 9 million megawatt-hours of electricity, equal to the amount of electricity consumed by more than 96,000 households over that period.[ii]

To maximize the benefits for the environment and residents of the region, every state should commit to investing carbon revenue in clean energy and adopt the best practices for investment of carbon cap revenue developed by leading states in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative has contributed to the 60 percent reduction in carbon emissions from power plants in the region from 2005 to 2017, while reducing energy bills for consumers in Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states.

- RGGI-funded investments in clean energy have cut energy use, saving residents, businesses and industries $658 million on energy bills.[iii]

- Health-threatening air pollution from power plants has fallen, reducing premature deaths, asthma attacks, and emergency room visits.[iv] According to a 2017 study, in the first six years of the program, improved air quality resulted in an estimated 9,000 avoided asthma attacks and helped prolong between 300 and 830 lives.[v]

- Electricity generation from wind turbines and solar panels in the region increased nine-fold from 2008 to 2017, thanks to RGGI investments, other policies, and declines in the price of clean energy technologies.[vi]

Smart investments of revenue from RGGI are driving clean energy progress in the region. Among the most effective investments have been those that:

- Focus on energy efficiency. Massachusetts dedicates most of its carbon auction revenues toward meeting the state’s ambitious energy efficiency goals. In 2017, Massachusetts’ efficiency investments enabled the state to avoid electricity consumption equal to 2.57 percent of electricity sales and cut global warming pollution.[vii]

- Help unlock private investments in clean energy. Connecticut’s commercial property assessed clean energy (C-PACE) program, partially supported through mid-2017 by revenue from RGGI, provides loans to businesses to finance clean energy investments that are repaid over time on property tax bills. From 2011 to 2017, the program supported more than $100 million in clean energy investments, saving customers nearly $200 million in energy costs over the lifetime of the projects.[viii]

- Extend the benefits of clean energy to low- and middle-income households. Maryland grants RGGI funds to local governments and community organizations that serve low- and moderate-income residents. In 2016 alone, these programs reduced energy use by 7.4 million kilowatt-hours and saved consumers $1.2 million on their electricity bills.[ix]

- Incentivize local governments to adopt clean energy. Massachusetts’ Green Communities program offers RGGI funds to cities and towns that reduce their environmental impact. More than 200 communities have committed to a set of clean energy policies, becoming eligible for $39 million in funding and unlocking greater energy savings than could have been obtained through direct spending of RGGI funds alone.[x]

- Reduce pollution from sources other than electricity generation. Sometimes, the most important and cost-effective clean energy investments can be found outside the electricity sector. Maine, for example, for several years earmarked 35 percent of carbon auction funds for measures to reduce pollution from home heating.[xi] As a result, thousands of Mainers installed high-efficiency ductless heat pumps and reduced their home heating bills.[xii]

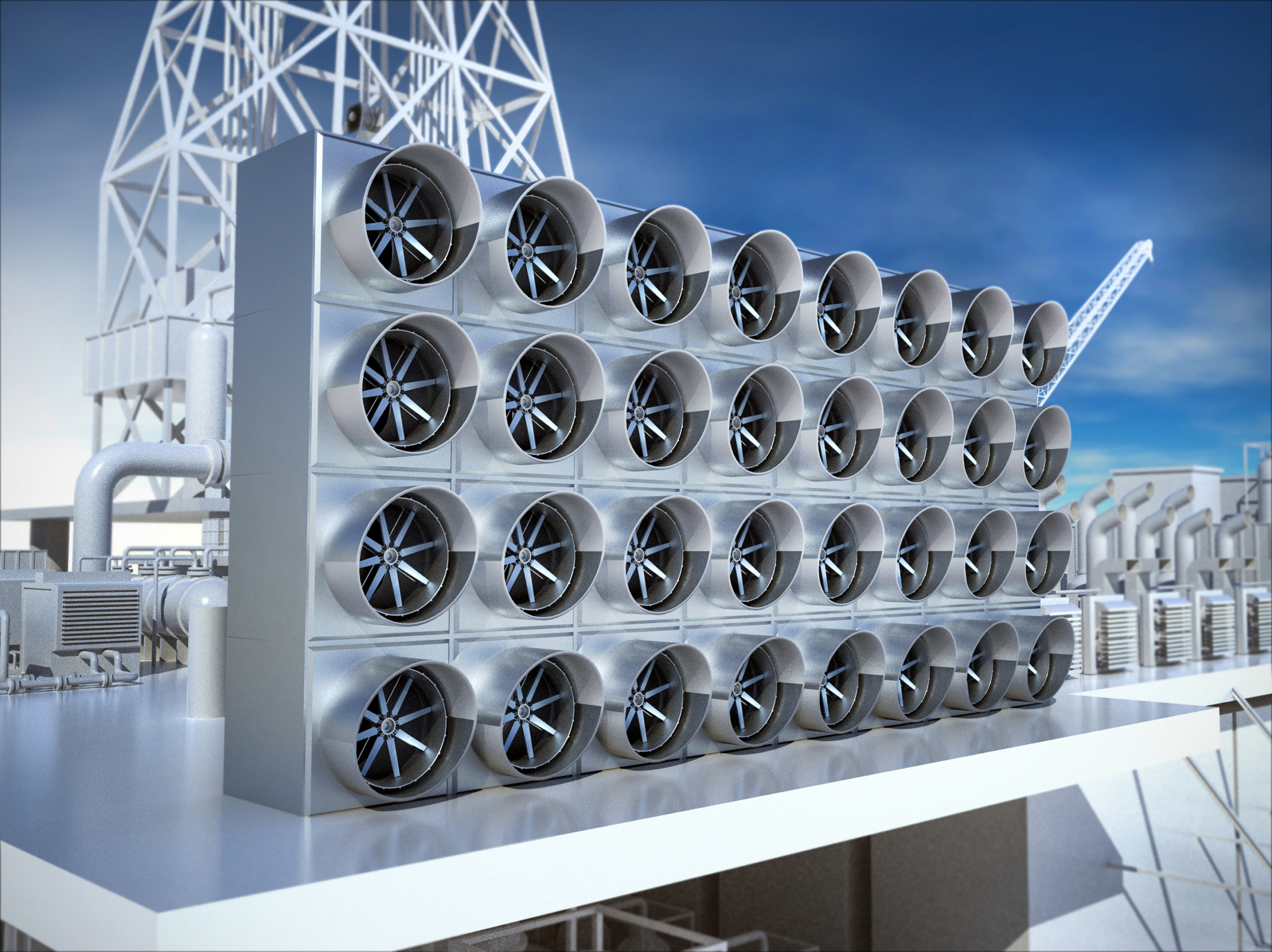

- Advance the next generation of clean energy technologies. Because more than one-third of New York State’s global warming pollution results from heating, cooling and ventilating buildings, New York uses some of its carbon auction revenues to spur research into technologies that will help reduce building energy use and future emissions.[xiii]

Not every investment made with carbon revenue has helped to move the region toward a clean energy future. States should avoid common pitfalls, including:

- Diverting carbon revenue to cover budget deficits. New York, New Jersey (before it withdrew from RGGI in 2012) and other states have used money from RGGI fees to cover shortfalls in the state budget rather than reducing climate pollution. In New Jersey, for example, the diversion of $65 million in fiscal year 2010 meant that consumers and businesses received less help improving energy efficiency.[xiv]

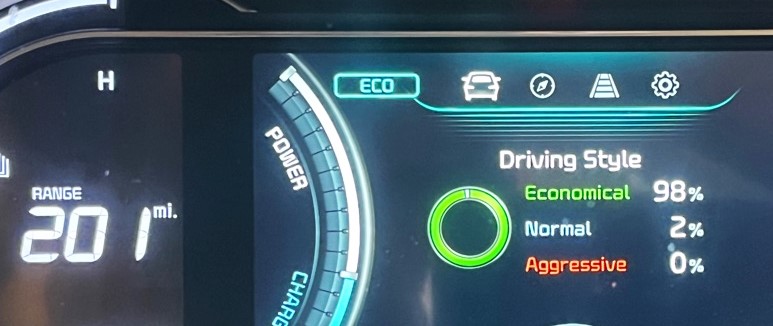

- Spending money on programs that do little or nothing to promote the region’s long-term transition to clean energy. Maryland used RGGI funds help purchase propane- and natural gas-powered vehicles, which, though they produce less carbon pollution than conventional vehicles, are not as clean as electric vehicles and commit the state to continued use of dirty fuels.[xv]

To maximize the benefits of the regional carbon program, states must make smart decisions to implement it – especially when it comes to investing revenue in clean energy. To get the most benefit out of RGGI:

- New Jersey and Virginia should propose and other states should approve a strong cap on carbon pollution from the states’ power plants. According to an analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), for New Jersey a strong cap would be 12 to 13 million tons per year.[xvi] For Virginia, NRDC’s analysis shows a strong cap would be 28 million tons.[xvii]

- States should spend revenues from the sale of pollution allowances to accelerate the region’s transition to a clean energy future.

- Virginia should formally join the regional carbon program via legislative action so that it can ensure that auction revenues are spent on policies that will deliver the greatest carbon pollution reductions.

- States should not divert carbon revenues to unrelated purposes.

[i] The sum of benefits presented in RGGI, Inc., The Investment of RGGI Proceeds through 2014, September 2016, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20180807173355/https://www.rggi.org/sites/de…, plus RGGI, Inc., The Investment of RGGI Proceeds in 2015, October 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20180925082929/https://www.rggi.org/sites/default/files/Uploads/Proceeds/RGGI_Proceeds_Report_2015.pdf and RGGI, Inc., The Investment of RGGI Proceeds in 2016, September 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005040840/https://www.rggi.org/sites/default/files/Uploads/Proceeds/RGGI_Proceeds_Report_2016.pdf.

[ii] Savings are over the lifetime of the clean energy upgrades and are based on the assumption that New Jersey achieves the same savings per dollar invested as the nine states currently in RGGI obtained in 2016. This estimate assumes New Jersey invests $344 million from 2020 to 2030, based on an emissions cap of 12 million tons and a carbon price of $2.88 to $3.26 per ton, per Natural Resources Defense Council et al., Letter to New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Catherine McCabe and New Jersey Board of Public Utilities President Joseph Fiordaliso, RE: Ensuring New Jersey’s Re-Entry into RGGI Includes a 2020 Carbon Cap Level That Maintains the Program’s Environmental Integrity, 5 June 2018. Data on nine-state 2016 benefits and investments in energy efficiency, renewable energy and greenhouse gas abatement from RGGI, Inc., The Investment of RGGI Proceeds in 2016, September 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005040840/https://www.rggi.org/sites/default/files/Uploads/Proceeds/RGGI_Proceeds_Report_2016.pdf. Mid-Atlantic households consumed an average of 8,465 kWh of electricity in 2015, per U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, Table CE2.2: Fuel Consumption in the Northeast – Totals and Averages, May 2018.

[iii] See note 1.

[iv] Abt Associates, Analysis of the Public Health Impacts of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, 2009-2014, January 2017, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170313222319/http://www.abtassociates.com/….

[v] Ibid.

[vi] U.S. Energy Information Administration, Electricity Data Browser, accessed at www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/ on 15 May 2018.

[vii] Weston Berg et al., American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, The 2018 State Energy Efficiency Scorecard, October 2018.

[viii] Connecticut Green Bank, 2017 Annual Report, no date, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005043743/https://www.ctgreenbank.com/w….

[ix] Maryland Energy Administration, 2016 LMI Program – Energy Savings Summary, no date, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20180514194457/http://energy.maryland.gov/govt/Documents/FY16%20LMI%20Program%20Results.pdf.

[x] Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, Green Community Designations Reach Two Hundred and Ten, 20 July 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20180724061259/https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/07/20/map-summary-green-communities-210.pdf.

[xi] 126th Maine Legislature, An Act To Reduce Energy Costs, Increase Energy Efficiency, Promote Electric System Reliability and Protect the Environment, L.D. 1559, 5 June 2013, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005165534/http://legislature.maine.gov/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=HP1128&item=1&snum=126.

[xii] Efficiency Maine, FY2017 Annual Report, revised 2 January 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005171414/https://www.efficiencymaine.com/docs/FY2017-Annual-Report.pdf, p. iii.

[xiii] NYSERDA, “NextGen HVAC Innovation Challenges” Program Opportunity Notice (PON) 3519, accessed 16 August 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005171956/https://portal.nyserda.ny.gov/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=00Pt0000007X4SBEA0, and NYSERDA, New York’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative-Funded Programs Status Report, Quarter Ending December 31, 2017, Final Report, June 2018, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005171907/https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/-/media/Files/Publications/Energy-Analysis/RGGI/2017-Q4-RGGI-status-report.pdf.

[xiv] Maria Gallucci, “Call for NJ Governor to Repay $65 Million to Carbon Fund,” Reuters, 31 May 2011, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20181005162724/https://www.reuters.com/article/idUS63172127920110531.

[xv] Mike Jones, Transportation Program Manager/Clean Cities Coordinator, Maryland Energy Administration, personal communication, 23 August 2018.

[xvi] Natural Resources Defense Council et al., Letter to New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Catherine McCabe and New Jersey Board of Public Utilities President Joseph Fiordaliso, RE: Ensuring New Jersey’s Re-Entry into RGGI Includes a 2020 Carbon Cap Level That Maintains the Program’s Environmental Integrity, 5 June 2018.

[xvii] Natural Resources Defense Council, NRDC Comments on VA DEQ’s Proposed Regulations for Emissions Trading (9VAC5 Chapter 140, Rev. C17), 9 April 2018.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Gideon Weissman

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Find Out More

Five key takeaways from the 5th National Climate Assessment

Carbon dioxide removal: The right thing at the wrong time?

Fact file: Computing is using more energy than ever.