Alana Miller

Policy Analyst

With more EVs on the road, and many more coming soon, cities will face the challenge of where electric vehicles will charge, particularly in city centers and neighborhoods without off-street residential parking. The good news is that smart public policies, including those already pioneered in cities nationally and internationally, can help U.S. cities lead the electric vehicle revolution while expanding access to clean transportation options for those who live, work and play in cities.

The adoption of large numbers of electric vehicles (EVs) offers many benefits for cities, including cleaner air and the opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Electric vehicles are far cleaner than gasoline-powered cars, with lower greenhouse gas emissions and lower emissions of the pollutants that contribute to smog and particulate matter.[1]

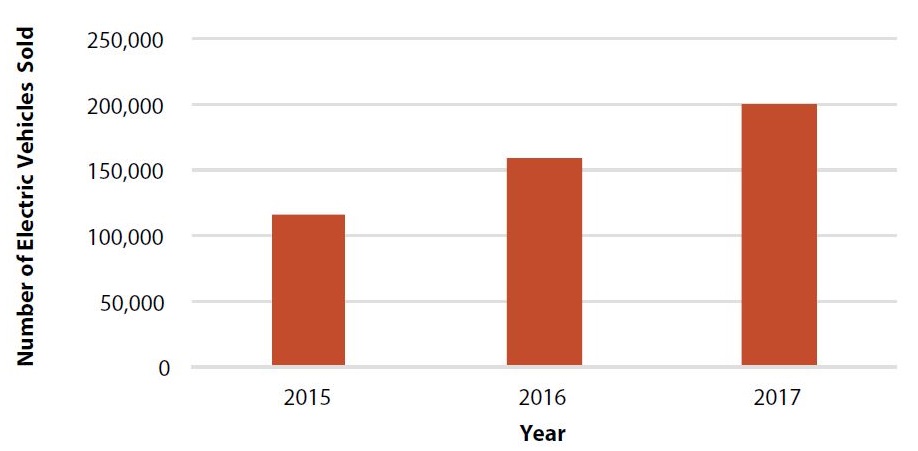

The number of EVs on America’s streets is at an all-time high. Throughout 2016, sales of plug-in electric vehicles increased nearly 38 percent.[2] In 2017, sales of electric vehicles were up again, increasing 32 percent over the year.[3] The introduction of the Chevy Bolt, Tesla’s Model 3 and other affordable, long-range electric vehicles suggests that growth in EV sales is just beginning. In fact, Chevrolet’s Bolt EV was named Motor Trend’s 2017 Car of the Year.[4]

But with more EVs on the road, and many more coming soon, cities will face the challenge of where electric vehicles will charge, particularly in city centers and neighborhoods without off-street residential parking.

The good news is that smart public policies, including those already pioneered in cities nationally and internationally, can help U.S. cities lead the electric vehicle revolution while expanding access to clean transportation options for those who live, work and play in cities.

Figure ES-1: U.S. EV Sales by Year, 2015-2017[5]

Electric vehicles are poised for explosive growth.

Technological gains that allow electric vehicles to drive farther, charge faster, and be produced more affordably are revolutionizing the vehicle market. With adequate policy and infrastructure investments, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates that, globally, more than half of new cars sold by 2040 will be electric vehicles.[6]

Cities need to be ready for an influx of electric vehicles.

In a few short years, tens of thousands of electric vehicles could hit city streets across America, from Portland, Maine, to Portland, Oregon. Yet, as of now, most cities are unprepared for this pending influx. These vehicles will need a place to charge, so public access to EV charging stations will be critical, especially since only about half of vehicles in the U.S. have a dedicated off-street parking space, like a driveway or garage.[7]

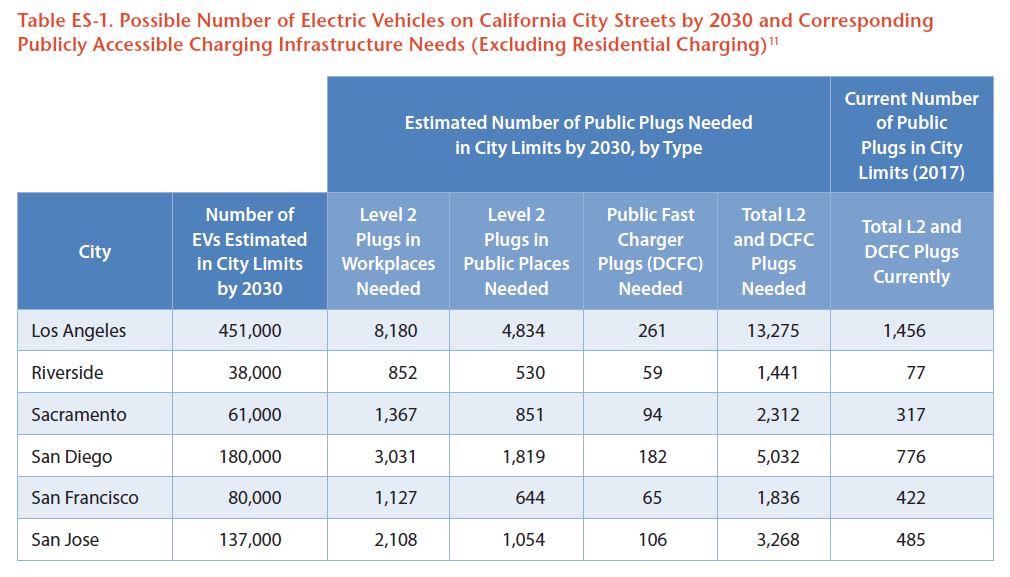

Major cities will require the installation of hundreds to thousands of publicly accessible electric vehicle chargers in order to serve the increased demand for electric vehicles. Studies conducted separately by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the Electric Power Research Institute, and Pacific Gas & Electric estimate that 1-5.2 public fast chargers are needed to support 1,000 electric vehicles.[8] The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that 36 non-residential Level 2 chargers are necessary for every 1,000 electric vehicles.[9] Cities will also need to facilitate at-home charging since the majority of EV owners will need to park and charge their vehicles overnight at or near where they live.[10]

There are three primary types, or levels, of electric vehicle chargers – Level 1, Level 2 and DCFC (often referred to as “fast charging”).

This report recognizes the value of Level 1 chargers as a low-cost option at homes, workplaces, and some public parking areas (like airports), but focuses on Level 2 and fast charging (DCFC) for public spaces, which are the chargers you would expect to find curbside, at workplaces and businesses, in parking garages and in other public areas.

Table ES-1. Possible Number of Electric Vehicles on Selected U.S. City Streets by 2030 and Corresponding Publicly Accessible Charging Infrastructure Needs[13]

The world’s leading EV cities have adopted key policies that enable urban residents to own and operate electric vehicles. In particular, these cities have been able to deliver electric vehicle infrastructure to urban drivers through innovative parking and planning policies, including:

Electric vehicle charging port on a lamppost in London. Credit: Jason Cartwright via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Leading cities are encouraging shared mobility options and reforming parking policies to expand access to electric vehicle travel and reduce conflicts over parking.

Electric vehicles are an essential tool for cities to combat global warming and air pollution, and offer consumer benefits like lower fuel costs. Technological developments mean that EVs are poised to hit the market in record numbers. However, there is a lot left to be done. If cities fail to develop comprehensive plans for EV charging now, they risk being unprepared for large numbers of EVs hitting local streets in coming years.

In order to be successful, cities will need to develop comprehensive solutions to accommodate electric vehicles, including convenient opportunities for charging. Some specific strategies include:

[1] Alternative Fuels Data Center, Emissions from Hybrid and Plug-In Electric Vehicles, archived at web.archive.org/save/https://www.afdc.energy.gov/vehicles/electric_emissions.php, 6 October 2017.

[2] Veloz, Sales Dashboard, accessed 13 February 2018, at http://www.veloz.org/sales-dashboard

[3] Ibid.

[4] Angus MacKenzie, MotorTrend, Chevrolet Bolt EV Is the 2017 Motor Trend Car of the Year, 14 November 2016, archived at web.archive.org/web/20171127233707/http://www.motortrend.com/news/chevrolet-bolt-ev-2017-car-of-the-year.

[5] See note 2.

[6] Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Electric Vehicle Outlook 2017, July 2017.

[7] Elizabeth Traut et al., “U.S. Residential Charging Potential for Electric Vehicles,” Transportation Research, 25(D): 139-145, doi: 10.1016, December 2013.

[8] Central estimate from NREL is 1 – 3.3 ports per 1,000 EVs: Eric Wood et al., National Renewable Energy Laboratory, National Plug-In Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Analysis, September 2017; Electric Power Research Institute estimated 1.7 – 5.2 fast charge ports per 1,000 EVs: EPRI, Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment Installed Cost Analysis, Final Report, October 2014; Pacific Gas & Electric estimated 2.2 – 3.7 ports per 1,000 EVs: M. Metcalf, Electric Program Investment Charge (EPIC), Pacific Gas & Electric, September 2016.

[9] Eric Wood et al., National Renewable Energy Laboratory, National Plug-In Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Analysis, September 2017.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Informed by: ChargePoint, Driver’s Checklist: A Quick Guide to Fast Charging (factsheet), archived at web.archive.org/web/20180105185743/https://www.chargepoint.com/files/Quick_Guide_to_Fast_Charging.pdf

[12] Commuting distance: Elizabeth Kneebone and Natalie Holmes, Brookings, The Growing Distance Between People and Jobs in Metropolitan America, July 2016.

[13] Estimated vehicles and plugs: Using projection ratios from NREL’s September 2017 study (see note 9), we calculated the number of EVs that could be in major cities. See methodology for full details.

[14] Some city EV plans call attention to this challenge specifically, e.g. City of Houston, Electric Vehicle Charging Long Range Plan for the Greater Houston Area, archived at web.archive.org/web/20171006174135/http://www.houstontx.gov/fleet/ev/longrangeevplan.pdf, 6 October 2017.

[15] Rob Hull, “Want an Electric Car Charge Point On The Street Outside Your House? There’s A £2.5m Pot, But the Catch Is You Have To Apply Though Your Council,” This Is Money, archived at web.archive.org/web/20180206171837/http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/cars/article-4245190/How-electric-car…, 23 October 2017.

Policy Analyst

Policy Associate