How do dating apps use my data? A video explainer

Ever used a dating app? That data doesn’t stay private for long. PIRG advocate R.J. Cross explains what happens next with help from Finn Myrstad of the Norwegian Consumer Council.

From the video – originally published 2/10/2021:

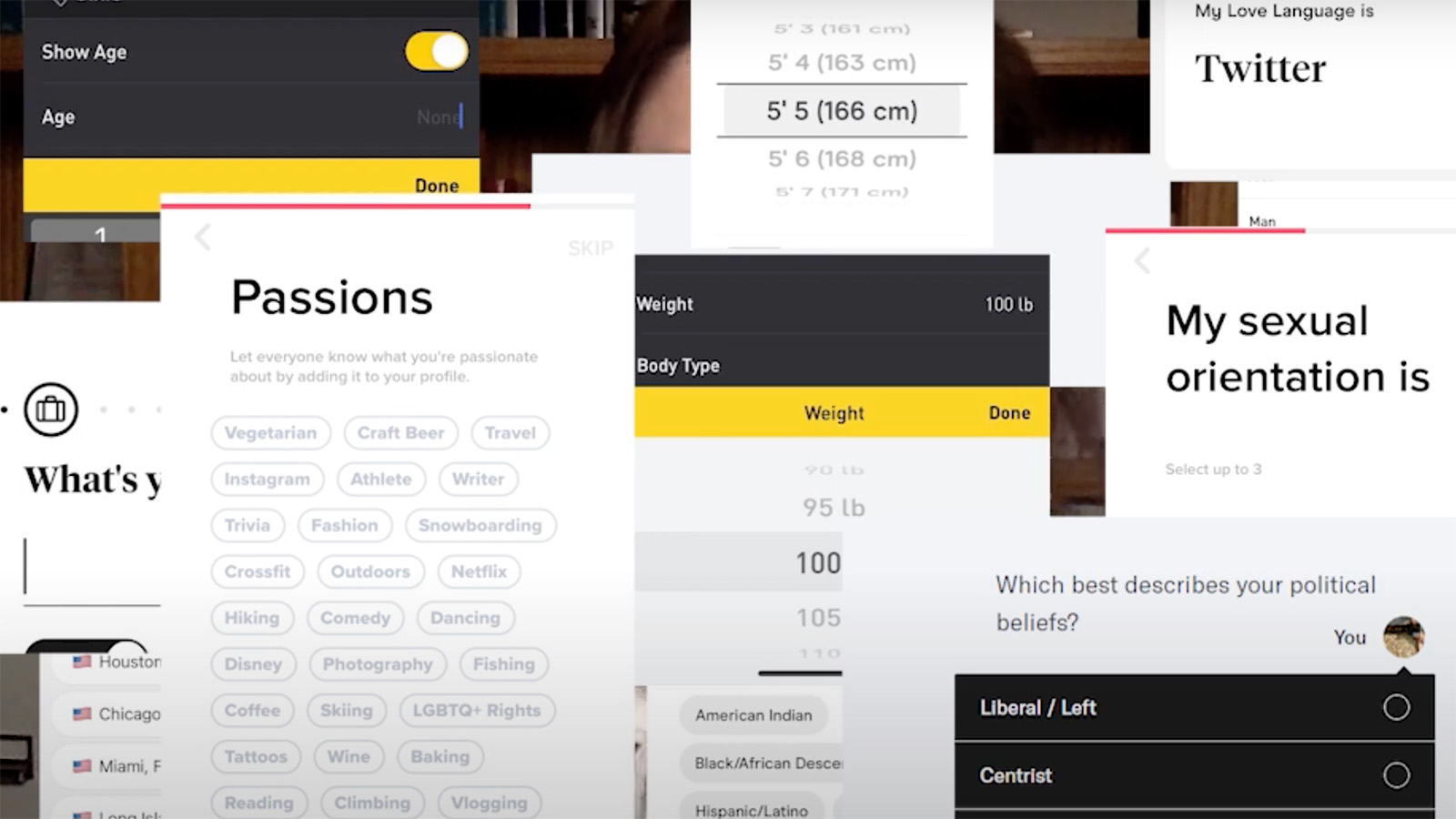

My dating apps all have my age, gender, location, email, birthdate, ethnicity, education level, sexual orientation, height, weight, field of employment, political affiliation, hobbies, a sample of my terrible sense of humor, and photos that I say are recent but were definitely all taken in my early 20s.

I also gave Tinder access to all my Facebook likes and entire friends list, and if you’ve ever used OkCupid, you know they have those personality questions to help determine compatibility… I answered 419 questions on that website.

I know they had that data, I willingly gave those apps that information in the mobile pursuit of love, I’m not that dumb. But it turns out there are a lot of details about how these apps collect, share, and use my data that I didn’t know.

Like whenever I joined one of the platforms, I was agreeing to the use of a whole host of tracking technologies embedded in these apps and sites by third-party companies that monitor my behavior and learn enough about my actions to predict what I’m going to do next in order to sell me stuff online.

When you give a dating app information about yourself, you’re never really giving just that company your data.

If you’ve ever used Tinder, OkCupid, Match dot com, Hinge, Plenty of Fish or whatever the hell LoveScout24 or Twoo are, they’re all owned by the same company that operates at least 45 dating sites. Use just one, and all of them can have your data!

Use Bumble or Hinge? If either of those get sold to another company, then that company can have your data!

But that’s nothing. If you’ve ever used literally any of these apps or sites before, then your data is being shared with companies that you had no idea even existed.

Uncovering the inner-workings of the data sharing ecosystem is something that Finn Myrstad, the director of digital policy at the Norwegian Consumer Council, and his group did just last year so take it from him.

“So there are lots of different software kits integrated in the app that collect your data and share it with third parties. When we did our sweep of 10 apps last year, we saw that both Google and Facebook were heavily embedded in most apps, but we also discovered several other unknown companies that were receiving really sensitive information from the apps.”

“There are lots of other third-part companies that are there just to mine your data and then you have no way of stopping it.”

—Finn Myrstad, the director of digital policy at the Norwegian Consumer Council

Cookies, software development kits, web beacons – these are all types of technologies that companies that specialize in mining data can use to mine your data.

These third-party companies not only love to know info that you’ve explicitly given the app, they often track how many times a day you open the app, how long you’re on each time, what ads you’ve clicked on before and when those clicks turn into you actually buying something. They collect data on the type of device you’re using, your exact GPS coordinates, even your IP address, and in many cases an ID code that can be used to triangulate your behavior across apps and across devices in order to get a fuller picture of who you are online, how you shop, and then sell those insights to fourth-party companies.

__

So what do these companies do with your data once they’ve got it?

Companies in the [online advertising industry, also know, as the ad tech industry,] use it for market research, packaging up all that info they have about you into these little consumer profiles so they can sell the right to put an ad in front of your face at just the right time of day to the highest bidder. These companies know the right time of day and the right platform to catch you on because they’ve watched you, and they know that if you’re still swiping at 11:30 PM on a Wednesday, you are likely tipsy and the closest to buying a ceiling-mounted indoor laser light show that you’ve been looking at all day.

Now, it’s not just dating apps that are doing this. It’s basically every app that you’ve ever downloaded, ever. But dating apps are the apple of the ad tech industry’s eye. A 2019 industry study found that users are about twice as likely to click on an ad and buy something when it’s placed inside of a dating app than other types of apps. That’s because dating apps are uniquely well suited for the world of data-driven advertising.

According to the director of a major ad tech company, the high performance of ads inside of dating apps is exactly “due to the rich user data that [dating apps] are able to pass to advertisers.”

“Since dating apps have more complete user information, advertisers can serve more targeted ads.”

— Alex Kahn, Smart APAC Managing Director as reported by Janice Tran in Marketing, June 2019.

There’s another darker reason why consumers on these dating apps may be particularly susceptible to behavioral advertising – how many heavy emotions are involved and the fact that they’re really easy to manipulate. Listen to how the advertising head of Match Group, the business that runs 45 different dating sites, introduces this idea.

“If you’re on Tinder and thinking about where you’re going to go on Friday night…you’re also thinking what am I going to do, what am I going to wear, what’s my hair going to look like, what movies are on?…It’s a really context-heavy way to reach that single audience versus maybe Facebook which might know you’re single but your mindset on Facebook is very different. You’re leaning back and absorbing content versus thinking about a specific part of how you’re living your life.”

— Peter Foster, Match Group GM of global advertising and brand solutions “Should Brands Be Paying More Attention To Dating Apps?”, Marketing Week, March 2019

Mindset matters. Dating apps are a very emotionally charged experience compared to other apps and very actively remind you of the fact that you’re single – which for some people is awesome, and for others leads to a debilitating pit of despair and cat acquisition. A 2016 study by UNT psychologists looked at how dating apps can affect our mental state.

As one of the co-authors wrote, “When we as human beings are represented simply by what we look like, we start to look at ourselves in a very similar way: as an object to be evaluated.” – Trent Petrie, UNT psychologist, quoted in ‘How to Use Dating Apps Without Hurting Your Mental Health, According to Experts” Time, August 2018.

If I swipe through 50 potential partners and get zero matches, I might start to wonder if something’s wrong with me. And what a perfect time to suggest I buy a stupid serum that claims it’ll make my eyelashes thicker or something else that won’t make me lovable but might seem like a quick solution to my sadness and probably comes with free-two day shipping. Shopping when you’re sad is a real economic phenomenon called the ‘loneliness loop’ – that cycle between feelings of inadequacy and higher consumption. Economists have been studying it for decades. These apps can pretty easily affect your emotional state and then provide companies the opportunity to profit off of it.

It’s a tad unsettling. We know that dating apps themselves track who I swipe right on. It’s not a leap to imagine ad tech companies noting that I seem to like guys with beards or chicks with curly hair and then showing me ads of people who look like that falling madly in love with people who use that eyelash serum or drive the newest model of SUV or have that ceiling-mounted indoor laser light show in their bathroom for some reason. The capacity for using our data to influence behavior gets a lot scarier when you think of some of the other implications – election interference a la Cambridge Analytics, propaganda and misinformation, the very concept of the freedom of thought. Using consumer data to manipulate behavior is just that – it’s a form of manipulation. And we’re just beginning to understand how it’s being used.

The good news is that there are groups questioning why using dating or really any other kind of app should require that you consent to surveillance that’s been used to see you stuff, all with very few regulatory limits. U.S. PIRG has joined groups like Public Citizen, the Consumer Federation of America and the Center for Digital Democracy in calling on U.S. decision makers to improve consumer data protection laws and investigate the data sharing practices of both dating and health apps in particular.

—

So whether you choose to celebrate this Valentine’s Day by swiping away or joining me in now throwing my phone under a moving train and finding somewhere remote to live off the land, stay on the lookout, and be safe.

Read the Norwegian Consumer Council’s study.

Read about more of PIRG’s work to protect people’s personal data-even data collected by kids toys.

Topics

Authors

R.J. Cross

Director, Don't Sell My Data Campaign, PIRG

R.J. focuses on data privacy issues and the commercialization of personal data in the digital age. Her work ranges from consumer harms like scams and data breaches, to manipulative targeted advertising, to keeping kids safe online. In her work at Frontier Group, she has authored research reports on government transparency, predatory auto lending and consumer debt. Her work has appeared in WIRED magazine, CBS Mornings and USA Today, among other outlets. When she’s not protecting the public interest, she is an avid reader, fiction writer and birder.

Find Out More

“Certified natural gas” is not a source of clean energy

The Auto Lemon Index

What’s going on up there? The potential for solar on superstores