Abigail Bradford

Policy Analyst

Communities across the U.S. – from rural towns to big cities – are increasingly adopting composting programs to cut the amount of waste they pay to dump at landfills and trash incinerators. Composting can replenish soils vital for growing food; cut methane emissions and pull carbon out of the atmosphere; and replace harmful synthetic fertilizers. There are accessible steps that every community can take to realize the benefits of composting.

America throws out immense amounts or trash, most of which is dumped into landfills or burned in trash incinerators. This is a costly system that damages the environment and harms our health. Luckily, communities across the country are turning toward a common-sense and beneficial solution: composting. Composting programs divert organic material – such as food scraps, leaves, branches, grass clippings and other biodegradable material – away from landfills and incinerators and turn it into a valuable product. Compost can replenish and stabilize soil, helping to boost and sustain food production in the future. It can also help pull carbon out of the atmosphere, helping to tackle global warming, and replace polluting chemical fertilizers, protecting public health.

Americans landfilled or incinerated over 50 million tons of compostable waste in 2015. That is enough to fill a line of fully-loaded 18-wheelers, stretching from New York City to Los Angeles ten times.

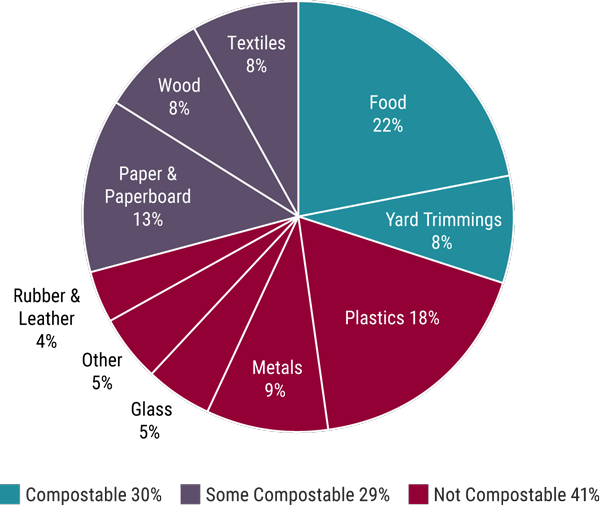

The system of collecting, landfilling and incinerating waste is a costly one that contributes to global warming and creates toxic air and water pollution. Composting could reduce the amount of trash sent to landfills and incinerators in the U.S. by at least 30 percent.

Figure ES-1: Materials Landfilled and Incinerated in the U.S. in 2015 by Material

Thanks to strong composting and recycling programs, San Francisco has reduced the amount of trash it sends to landfills by 80 percent and composts 255,500 tons of organic material each year. The state of Vermont passed a Universal Recycling Law in 2012 and is phasing in policies and programs until all of its recyclables, leaf and yard debris, food scraps and other organics will be banned from landfills in 2020.

A growing number of cities, towns and states are recognizing the benefits of composting programs. In just the last five years, the number of communities offering composting programs has grown by 65 percent. By following the best practices of programs around the country, American communities can launch successful composting programs that reduce waste, contribute to a sustainable food system, help tackle global warming, and reduce harmful air and water pollution.

Compost can help create a robust and sustainable agricultural system.

Topsoil, the nutrient-rich layer of soil vital for growing food, is being degraded and eroded at alarming rates, threatening our ability to grow enough food in the future.According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, one-third of the world’s topsoil is already degraded, and topsoil in the United States is eroding at more than nine times its natural rate of replacement.

Composting helps tackle global warming.

Organic waste does not decompose in the dark, low-oxygen conditions in landfills. Instead, its degradation produces methane, a greenhouse gas about 56 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Landfills are the nation’s third-largest source of methane emissions, emitting 108 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2017 – more than the total emissions of 34 individual states in 2016. Composting organic material could significantly reduce methane emissions.

Unlike landfilling, composting organic material helps plants and microorganisms to grow and actually pulls carbon out of the atmosphere. One model found that applying compost to 50 percent of California’s land used for grazing could sequester the amount of carbon currently emitted by California’s homes and businesses.

Compost can replace synthetic chemical fertilizers, which can:

To promote composting, cities and towns should adopt community-wide composting programs.

Most town-wide or city-wide composting programs work just like trash and recycling services – residents and businesses put their organic waste in a separate bin by the curb each week and it is picked up by a truck and brought to a composting facility. These programs are typically run by municipalities in conjunction with private haulers and composting facilities, but some communities allow private companies to operate in their town or city independently. In some communities, residents and businesses drop off their organic waste at a designated location, which requires fewer city resources but results in less collected organic material.

Successful composting programs share several characteristics:

Local governments can also combine the cost of organic waste pickup with trash and recycling, so that participants do not pay an extra fee, which is a barrier to participation.

In addition to taking the steps above to create successful community-wide composting programs, cities, towns and counties should also:

To support local composting programs, the federal government and state governments should:

Policy Analyst

Policy Associate