Gideon Weissman

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Childhood Hunger in America’s Suburbs shows the changing geography of childhood hunger at a time of growing suburban poverty. This report demonstrates that the risk of childhood hunger is an issue affecting nearly every American community, including communities that might otherwise think that hunger is a problem that occurs “somewhere else.”

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Fair Share Education Fund

The geography of childhood hunger in America is changing.

Among schools for which accurate trends can be tracked, 42 percent of American public school children were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch before the Great Recession.[i] By the school year ending in 2013, 51 percent of children were eligible. Of the students newly eligible for school lunch assistance, nearly half lived in the suburbs.

Suburban public schools still have a lower percentage of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunches than schools in the rest of the country. But the rise of child poverty in suburban areas means that suburbs increasingly look like the rest of America when it comes to the prevalence of poor children.

Today, there are likely more American children who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch in suburbs than in towns and rural areas combined. And while food insecurity in the aggregate is still greater in the cities than in the suburbs, between the school years 2006-07 and 2012-13, the number of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch grew at a much faster rate in the suburbs than in cities, rural areas or small- to mid-sized towns.

A review of data from the National Center for Educational Statistics finds:

Nationwide, the Great Recession made the risk of childhood hunger greater. Among public schools for which accurate comparisons could be made, the number of public school children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch increased by nearly 4 million. (This number includes 49 states plus Washington, D.C.; Nevada did not report complete data to the U.S. Department of Education.)

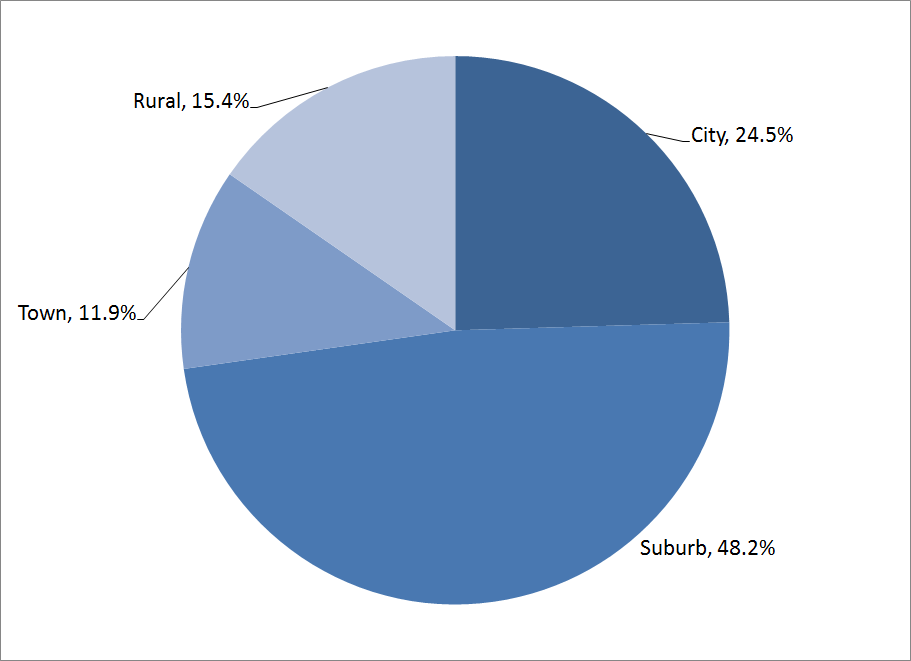

The geography of school lunch eligibility has changed since the Great Recession. A strong plurality of students newly eligible for the free or reduced-price school lunch program lives in the suburbs: 48 percent. By comparison, 15 percent live in rural areas, 25 percent live in cities and 12 percent live in small- or mid-sized towns. (See Figure ES-1.)

Of public school children eligible for free or reduced lunch nationwide, nearly one-third now live in the suburbs. Among students from public schools included in this study, nearly 6.5 million suburban children were eligible for free or reduced lunch in 2012-13, more than the number of children from rural communities and towns combined.

Compared to the findings in last year’s Fair Share Education Fund analysis of childhood hunger in 2011-12, the trend toward increasing suburban poverty has continued, with a greater share of suburban children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch in this analysis compared to last year’s.

The suburbs now look more like the rest of America when it comes to poverty and children living in food-insecure households. The share of suburban students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch is catching up to the share of eligible students in other types of communities.

Figure ES-1. Share of Public School Students Newly Eligible for Free or Reduced-price Lunch by Locale, from 2006-07 to 2012-13

This analysis comes as other data shed additional light on how much worse American poverty and hunger have become.

Childhood Hunger in America’s Suburbs shows the changing geography of childhood hunger at a time of growing suburban poverty. This report demonstrates that the risk of childhood hunger is an issue affecting nearly every American community, including communities that might otherwise think that hunger is a problem that occurs “somewhere else.”

[i] See “Understanding the Data in this Report” in downloadable PDF.

[ii] 2013: Carmen DeNavas-Walt and Bernadette D. Proctor, U.S. Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013, September 2014; 2007: Carmen DeNavas-Walt et al., U.S. Census Bureau, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007, August 2008.

[iii] Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Household Food Security in the United States in 2013, available at ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err173.aspx , September 2014.

[iv] Fred Dews, Brookings Institute, The Rapid Rise of Suburban Poverty, available at brookings.edu/blogs/brookings-now/posts/2014/06/chart-rapid-rise-of-suburban-poverty, 11 June 2014.

[v] Elizabeth Kneebone, Brookings Institute, The Growth and Spread of Concentrated Poverty, 2000 to 2008-2012, available at brookings.edu/research/interactives/2014/concentrated-poverty#/M10420, 31 July 2014.

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Fair Share Education Fund