Who Pays for Parking?

The United States currently spends $7.3 billion per year to encourage people to drive to work through the federal income tax exclusion for commuter parking. The “commuter parking benefit” puts more cars on the road in our most congested cities at the most congested times of day––exactly the opposite of what most cities want or need. Who Pays for Parking? documents the cost of the commuter parking for cities and highlights tools cities can use to reclaim their streets.

The United States currently spends approximately $7.3 billion per year to encourage people to drive to work through the federal income tax exclusion for employer-provided and employer-paid commuter parking. The “commuter parking benefit” puts more cars on the road in our most congested cities at the most congested times of day––exactly the opposite of what most cities want or need.

In an effort to counteract the effects of the commuter parking benefit, America also subsidizes people not to drive to work through the “commuter transit benefit”––a $1.3 billion program that enables workers to receive transit passes or vanpool services from their employers tax-free. The transit benefit attempts to support transportation policy goals, but it is overshadowed by the parking tax benefit’s much larger adverse impact.

America’s tax policy for subsidizing commuter travel is inefficient, inequitable, and lacks a coherent policy purpose. This report proposes a series of reforms to improve and modernize the tax treatment of commuter benefits––saving taxpayer funds, improving the quality of workers’ commutes, and making our cities better places to live and work.

America’s current tax treatment of commuter benefits adds cars to the roads and delivers the greatest benefits to those who need them least. According to Subsidizing Congestion, a 2014 report by the same authors of this report:

- The parking benefit adds approximately 820,000 automobile commuters to the roads, traveling more than 4.6 billion additional miles per year. The transit benefit removes only about a tenth as many vehicles from the roads––largely because it reaches far fewer people than the parking benefit.[i]

- Only about a third of American workers receive any tax savings at all from the parking tax benefit––with the greatest benefits accruing to higher-income workers who drive to work in the nation’s large cities, where parking is most expensive.

Commuter parking benefits amount to tens of millions of dollars in subsidies to people driving to work in major American downtowns.

- The cost to taxpayers of the parking benefit for workers in just 25 major US central business districts (CBDs) likely exceeds $700 million per year. The districts in which the benefit imposes the greatest cost are those in which parking is most expensive and the percentage of people driving to work is highest.

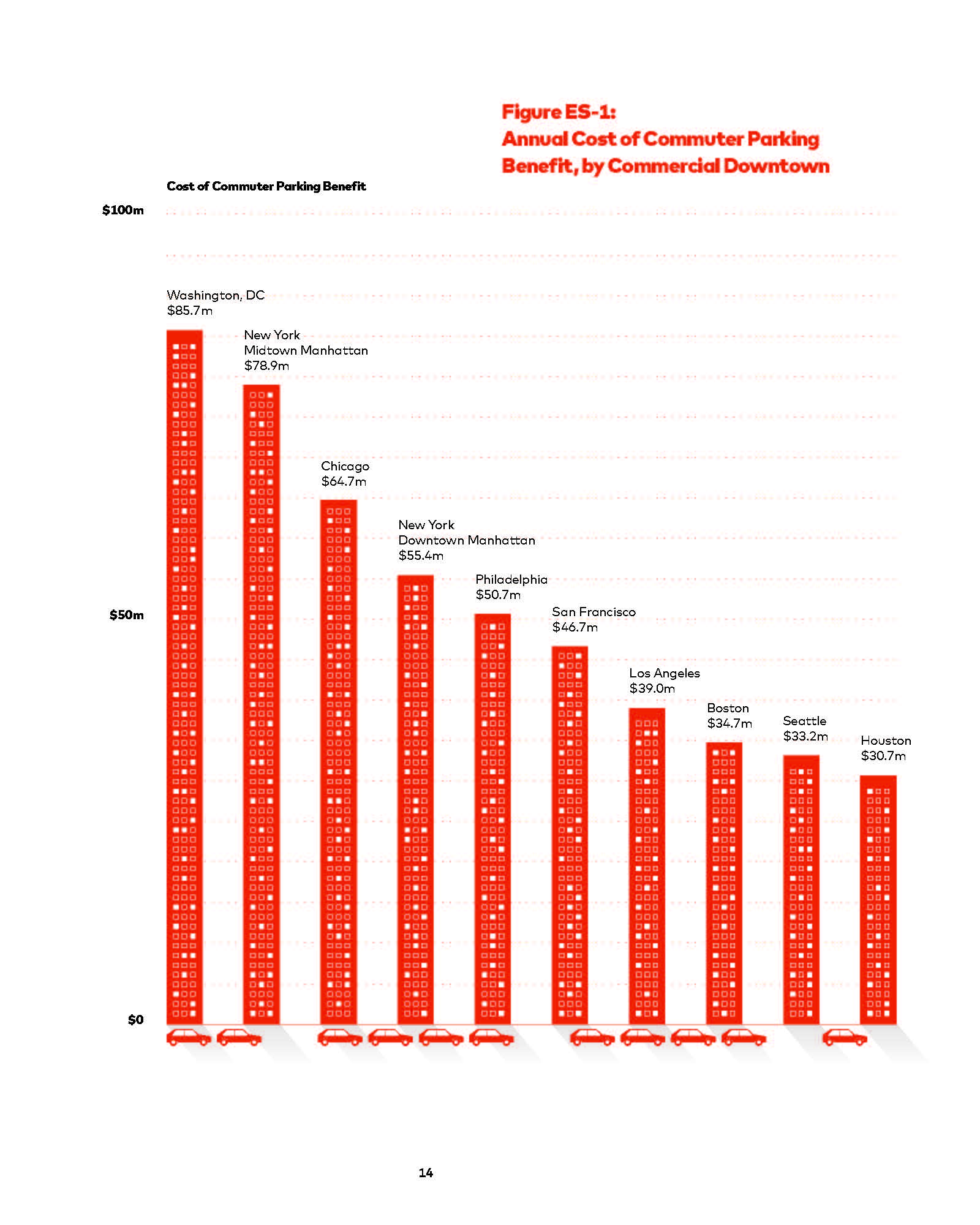

- Of the 25 CBDs evaluated, the total cost of the commuter parking benefit is highest in downtown Washington, DC, at an estimated $86 million a year, followed by Midtown Manhattan, Chicago, Downtown Manhattan, and Philadelphia. (See Figure ES-1.)

Figure ES-1. Annual Cost of Commuter Parking Benefit by Commercial Downtown

- These tax expenditures for commuter parking distort daily transportation decision-making. Research shows that providing “free” car parking offsets the effects of incentives for transit use, carpooling, and bicycling.[ii]

- Eliminating the commuter parking benefit would remove approximately 66,000 cars from the road in these 25 central business districts, averting more than 370 million vehicle-miles traveled per year.

Cities can take three immediate steps to counteract the negative effects of the commuter parking benefit on congestion, public health, and urban quality of life:

- Expand access to transit benefits: Cities such as San Francisco, New York, and Washington, DC, now require many businesses to offer benefits for transit, bicycling, and/or carpooling to their employees. Early experience with these programs suggests that they can dramatically increase the number of workers able to take advantage of transit benefits and change commuter behavior. A study in the San Francisco Bay Area found that commuter benefit requirements have led 44,000 people to change their travel behaviors, avoiding 86 million vehicle-miles traveled.[iii]

- Tax parking: Numerous US cities tax parking provided in commercial facilities, while cities in Australia and Britain now assess annual taxes on parking spaces, whether they are provided at no cost or for a price. Taxing parking helps cities recoup some of the revenue lost because of the tax benefit for commuter parking and counteracts some of the incentive to drive into central cities that the benefit provides. Several cities have even reinvested their parking tax revenues into public transportation or local street improvements in support of an expanded range of transportation choices.

- Enlist the private sector in expanding transportation options. Many cities work with employers, major institutions, and residents to reduce single-occupancy vehicle trips and encourage alternatives to driving. These transportation demand management (TDM) programs educate employers and workers about their commuting options and organize activities and contests to encourage people to try new ways of getting to work. Local and state laws can promote these partnerships by requiring or incentivizing employers and developers to provide support for transportation options.

In the long run, the federal government should consider more fundamental reforms to the nation’s tax treatment of commuter benefits. These steps could include:

- Eliminating or limiting the commuter parking benefit:Nations such as Australia, Ireland, Austria, and Sweden have established systems for taxing the value of employer-provided parking that could serve as a model for the United States. Such a system might:

- Require employers who pay directly for their employees’ parking to report the value of that parking as taxable income.

- Require employers who provide parking at no cost to their employees to calculate the value of parking at nearby garages and lots and report that value as taxable income.

The adoption of such a system would make no difference in the tax liability of the majority of Americans, who work in areas where parking is abundant and unpriced and, therefore, has little taxable value as defined by the IRS. It would, however, reduce the incentive to drive to work for those traveling every day to the centers of America’s largest and most congested cities.

- Expanding access to the transit benefit. In addition to requiring employers to offer transit benefits (as some major cities have begun to do), the federal government can expand access to transit benefits to independent contractors, the self-employed, workers in the “gig economy,” and others who currently are unable to benefit from them. Creating an income tax deduction for transit that is open to those who do not receive benefits through the workplace would allow for greater equity among different classes of employees and potentially support those who use transit for purposes other than commuting.

- Modernizing the transit benefit to include new and emerging modes of travel.A 21st-century system of commuter benefits should recognize the emergence of new “shared mobility” services and the growth of walking and biking by:

- Allowing expenditures for bikesharing to be eligible for tax-free commuter benefits.

- Allowing verified shared rides and “first mile/last mile” connections to transit via shared mobility services to be eligible for tax-free treatment. Current federal rules enable some trips via shared mobility services to be paid for through pre-tax earnings, but those rules push providers to use larger vehicles than necessary and do little to encourage the actual sharing of rides. Revising the eligibility rules for shared mobility providers can support the program’s intent of encouraging efficient travel that removes cars from the road.

- Investigating the potential of mileage-based benefits for employees who walk or bike to work, as exist in Belgium and the Netherlands. Even a reformed and expanded system of commuter transit benefits provides tax privileges to those with longer and more expensive commutes versus those who live closer to work or who use active modes of transportation. Creating a parallel benefit for those who walk or bike to work can further reduce single-passenger car travel and support the least energy-intense travel options.

- Collecting data and monitoring the performance of commuter benefits programs. Despite the roughly $8 billion-per-year cost of commuter parking and transit benefits, there has not been comprehensive study of their impact on the transportation system. Federal, state, and local governments should support research to better understand the effects of commuter benefits on travel behavior and adjust future benefits programs accordingly.

1. TransitCenter and Frontier Group, Subsidizing Congestion: The Multibillion-Dollar Tax Subsidy That’s Making Your Commute Worse, 2014, transitcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/SubsidizingCongestion-FINAL.pdf.

2. Andrea Hamre and Ralph Buehler, “Commuter Mode Choice and Free Car Parking, Public Transportation Benefits, Showers/Lockers, and Bike Parking at Work: Evidence from the Washington, DC Region,” Journal of Public Transportation 17, no. 2 (2014): 67–91, doi: 10.5038/2375-0901.17.2.4.

3. True North Research, Bay Area Commuter Benefits Program: Evaluation of Trip, VMT & Emission Impacts, 2015, 5, web.archive.org/web/20170727183435/http://www.baaqmd.gov/~/media/files/planning-and-research/commuter-benef….

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Elizabeth Berg

Policy Associate

Alana Miller

TransitCenter

Find Out More

Less driving is possible

Electric School Buses and the Grid

Shifting Gears