Trouble in the Air

Millions of Americans Breathe Polluted Air

In 2016, 73 million Americans experienced more than 100 days of degraded air quality. That is equal to more than three months of the year in which smog and/or particulate pollution was above the level that the EPA has determined presents “little to no risk.” To safeguard public health, the nation needs to preserve and strengthen existing air quality protections and reduce the future air pollution threats posed by global warming.

Note: Newer versions of this report are available: 2020 data and 2018 data.

People across America regularly breathe unhealthy air that increases their risk of premature death, asthma attacks and other adverse health impacts.

In 2016, 73 million Americans experienced more than 100 days of degraded air quality with the potential to harm human health. That is equal to more than three months of the year in which smog and/or particulate pollution was above the level that the EPA has determined presents “little to no risk.” Millions more people in urban and rural areas experienced less frequent but still damaging levels of air pollution.

To safeguard public health, the nation needs to preserve and strengthen existing air quality protections at the federal and state level and move to reduce the future air pollution threats posed by global warming.

Burning fossil fuels such as coal, diesel, gasoline and natural gas creates air pollution in the form of smog, particulates and air toxics. Wildfires, wood stoves, agricultural dust and other sources create additional air pollution. There is no documented safe level of exposure to some of these pollutants.[1]

- Smog, or ground-level ozone, causes a host of respiratory problems, ranging from coughing, wheezing and throat irritation to asthma, increased risk of infection, and permanent damage to lung tissue.[2]

- Particulate pollution (PM2.5) can cause similar respiratory harm and also trigger a range of cardiovascular problems, including heart attacks, strokes, congestive heart failure, and reduced blood supply to the heart.[3] These problems can result in increased hospital admissions and premature deaths. Particulate pollution has also been shown to trigger premature birth, raise the risk of autism, stunt lung development in children, and increase the risk that they may develop asthma.[4] Recent studies also implicate particulate pollution in an increased risk of dementia.[5]

- Levels of air pollution that meet current federal air quality standards can be harmful to health, especially with prolonged exposure. Researchers can detect negative health impacts, such as increased premature deaths, for people exposed to pollution at levels the EPA considers “good” or “moderate.”[6] Current federal standards are less stringent than those recommended by the World Health Organization. They may also fail to reflect the impact of frequent exposure to moderate levels of pollution. For these reasons, the analysis in this report includes air pollution at or above the level the EPA labels “moderate” and indicates in yellow or worse in its Air Quality Index.

Millions of Americans live in urban and rural areas that experience frequent smog and/or particulate pollution.

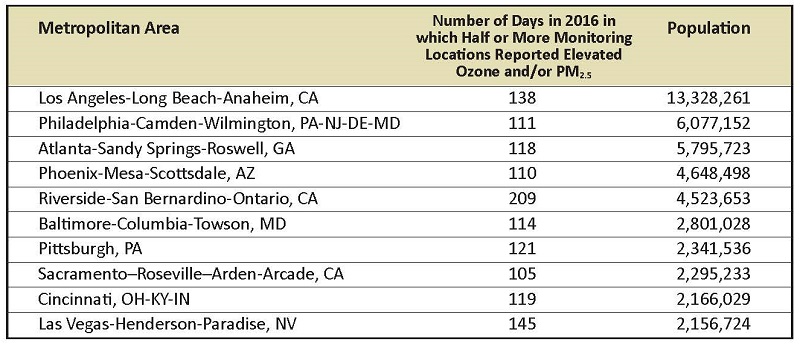

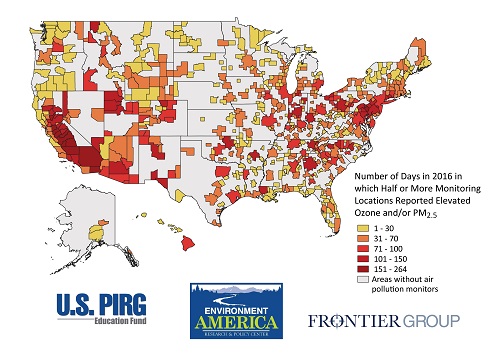

- 56 metropolitan and micropolitan areas and four rural counties experienced more than 100 days on which smog and/or particulate pollution was “moderate” or higher – in other words, above the level that the EPA has determined presents “little to no risk.” Seventy-three million Americans live in those places. (See Table ES-1.)

- Another 241 urban areas and 42 rural counties faced 31 to 100 days – a month or more – of smog and/or particulate pollution above the “little to no risk” level. Those places include large metropolitan areas such as Chicago, Miami and Hartford, and smaller communities such as Macon, Georgia; Yuma, Arizona; and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. These places are home to 173 million Americans.

Table ES-1. Ten Most Populated Metropolitan Areas with More than 100 Days of Elevated Air Pollution in 2016

Note: This count includes air pollution at or above the level the EPA labels “moderate” and indicates in yellow or worse in its Air Quality Index.

Figure ES-1. Both Urban and Rural Areas Experienced Frequent Smog and/or Particulate Pollution in 2016[7]

Smog pollution is a frequent health threat in some regions.

- 8 million people, living in 12 urban areas and two rural counties, were exposed to more than 100 days of elevated smog pollution in 2016. All of those places were located in inland California, where the wind carries pollution from urban centers, and hot, sunny days facilitate the reaction between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that creates smog.

- Another 159 million residents of 208 areas breathed air with excess ozone pollution on 31 to 100 days in 2016. Those urban areas and rural counties were located in 38 different states, plus the District of Columbia.

Particulate pollution affected people living in a broad range of places in 2016.

- 21 million people, living in 21 urban and rural areas, were exposed to more than 100 days of elevated particulate pollution in 2016. These urban areas and rural counties were located in California, Georgia, Louisiana, Montana, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

- An additional 132 places, home to 154 million Americans, experienced 31 to 100 days of elevated particulate pollution. These areas include many of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas, and also much less populated areas where wintertime wood-burning for heat and summertime wildfires create extensive particulate pollution.

Global warming threatens to exacerbate the nation’s smog and particulate pollution problems.[8] Higher temperatures will facilitate formation of smog and altered wind patterns may increase the number of days with stagnant air that prevents dilution of contaminants.[9] Wildfires, which generate particulate pollution and smog precursors that can travel hundreds of miles, are predicted to become more frequent and intense.[10]

To reduce the pollution that threatens the health of people across the country, and to avoid global warming-related increases in air pollution in the future, the nation should:

- Defend and build upon improvements in air quality achieved through rules implementing the Clean Air Act. Pollution reductions achieved under regulations of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 helped prevent more than 160,000 early deaths, 130,000 non-fatal heart attacks, and 41,000 hospital admissions in 2010 alone.[11] These benefits are in addition to those created by the original Clean Air Act. Maintaining the gains already achieved through implementation of the Clean Air Act and seeking greater emission reductions are crucial for ensuring that Americans can breathe cleaner air.

- Strengthen federal fuel economy standards for cars and light trucks. These standards are critical to the nation’s efforts to reduce global warming pollution from passenger vehicles.

- Continue to allow states to adopt stronger standards for pollution from vehicles to help reduce global warming emissions and health-threatening air pollution. The clean car standards pioneered by 13 states plus the District of Columbia have been highly effective in reducing pollution.

- Support policies at every level of government to reduce global warming pollution, including increasing the use of wind, solar and other clean energy, and placing state and regional limits on climate pollution.

[1] Michelle L. Bell, Roger D. Peng and Francesca Dominici, “The Exposure-Response Curve for Ozone and Risk of Mortality and the Adequacy of Current Ozone Regulations,” Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(4): 532-6, doi:10.1289/ehp.8816, April 2006; and World Health Organization, WHO Air Quality Guidelines for Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide, Global Update 2005, Summary of Risk Assessment, 2006, archived at web.archive.org/web/20170316035918/http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69477/1/WHO_SDE_PHE_OEH_06.02_e….

[2] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, The National Ambient Air Quality Standards: Ozone and Health (factsheet), no date, archived at web.archive.org/web/20170322214936/https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-04/documents/20151001hea… Kendall Powell, “Ozone Exposure Throws Monkey Wrench into Infant Lungs,” Nature Medicine, 9(5), May 2003; R. McConnell et al., “Asthma in Exercising Children Exposed to Ozone: A Cohort Study,” The Lancet 359: 386-391, 2002; N. Kunzli et al., “Association Between Lifetime Ambient Ozone Exposure and Pulmonary Function in College Freshmen – Results of a Pilot Study,” Environmental Research 72: 8-16, 1997; I.B. Tager et al., “Chronic Exposure to Ambient Ozone and Lung Function in Young Adults,” Epidemiology, 16: 751-9, November 2005.

[3] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, The National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution: Particle Pollution and Health (factsheet), no date; and J. Pekkanen et al., “Daily Variations of Particulate Air Pollution and ST-T Depressions in Subjects with Stable Coronary Heart Disease: The Finnish ULTRA Study,” American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 161: A24, 2000.

[4] L. Trasande, P. Malecha and T.M. Attina, “Particulate Matter Exposure and Preterm Birth: Estimates of U.S. Attributable Burden and Economic Costs,” Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(12): 1913-1918, dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510810, December 2016; Raanan Raz et al., “Autism Spectrum Disorder and Particulate Matter Air Pollution before, during, and after Pregnancy: A Nested Case-Control Analysis within the Nurses’ Health Study II Cohort,” Environmental Health Perspectives, 123: 264-270, dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408133, 1 March 2015; W.J. Gauderman et al., “The Effect of Air Pollution on Lung Development from 10 to 18 Years of Age,” The New England Journal of Medicine 351: 1057-67, 9 September 2004; and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, The National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution: Particle Pollution and Health (factsheet), no date.

[5] M. Cacciottolo et al., “Particulate Air Pollutants, APOE Alleles and Their Contributions to Cognitive Impairment in Older Women and to Amyloidodgenesis in Experimental Models,” Translational Psychiatry, doi:10.1038/tp.2016.280, 31 January 2017.

[6] Michelle L. Bell, Roger D. Peng and Francesca Dominici, “The Exposure-Response Curve for Ozone and Risk of Mortality and the Adequacy of Current Ozone Regulations,” Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(4): 532-6, doi:10.1289/ehp.8816, April 2006, and Qian Di et al., “Association of Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution with Mortality in Older Adults,” JAMA, 318(24): 2446-2456, doi:10.1001/jama.2017.17923, 26 December 2017.

[7] The map shows Census-designated metropolitan and micropolitan areas, plus rural counties that have an air pollution monitor. Note that Macon, Georgia, is mapped to Macon County. The towns of Bishop, CA; Rockland, ME; and Walterboro, SC, are not shown because they are not included in the Census Bureau shapefiles for mapping.

[8] Neal Fann et al., “Chapter 3: Air Quality Impacts,” The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program, dx.doi.org/10.7930/J0GQ6VP6, 2016.

[9] Climate Central, Stagnant Air on the Rise, Upping Ozone Risk, 17 August 2016, archived at web.archive.org/web/20170218012058/http://www.climatecentral.org/news/stagnation-air-conditions-on-the-rise….

[10] George Luber et al., “Chapter 9: Human Health,” Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program, doi:10.7930/J0PN93H5, 2014.

[11] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air and Radiation, The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act from 1990 to 2020, April 2011, archived at web.archive.org/web/20151019090948/https://www2.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-07/documents/fullreport….

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

Lawn care goes electric

Who are the top climate polluters in the country?

The Biden administration has released $1 billion in funding for urban trees. Here’s why that matters.