Sunshine Through the Gridlock

On a per-commuter basis, congestion levels are lower than they were five years ago, or even a decade ago.

This week saw the release of the Texas Transportation Institute’s (TTI) annual media-grabbing Urban Mobility Report. The report ranks U.S. metropolitan areas based on their levels of traffic congestion and tallies up the cost of congestion in wasted fuel and wasted money.

The headlines typically focus on the economic toll of congestion (estimated at $115 billion in 2009 by TTI) or measures of congestion for individual cities. This year, the TTI press release highlights the dramatic increase in congestion since 1982 and the (extremely mild) increase since 2008.

But the bigger and far more interesting story is this: the story of declining congestion in many American cities over the past decade.

Indeed, on a per-commuter basis, congestion levels are lower than they were five years ago, or even a decade ago. The number of hours spent in congestion per automobile commuter has declined by 7 hours per year since 2005, while the Travel Time Index (which measures the relative severity of rush hour traffic) has also gone down. More cities have experienced per-commuter congestion decreases since 2005 than have seen congestion worsen. And for a fair number of cities, the trend goes all the way back to 2000.

Even when one factors in a growing number of drivers, the amount of total delay on the nation’s roads is lower than in 2005, though it is higher than in 2000.

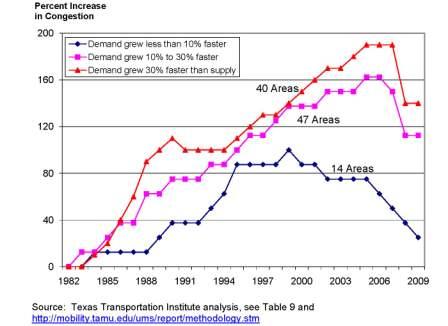

What the devil is going on? TTI suggests a couple of answers. First, they suggest — not very convincingly, in my view — that cities that have invested more in expanding transportation capacity have experienced lower levels of congestion growth. Why “not very convincingly”? For one reason (as the chart below shows) cities have experienced declines in congestion since 2005 regardless of how much highway capacity they have built. Second, the list of cities that has allegedly “kept pace” with travel growth through highway expansion is peppered with cities such as New Orleans, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh that have either lost population in recent years or have seen population stagnate.

The second reason they suggest for the drop in congestion is the collapsing economy. While the economy has undoubtedly been a big factor in the drop in congestion since the recession started in 2007, it does not explain why congestion is down relative to 2000.

The truth is that there is likely no single reason for the drop in congestion over the last decade. But I would put my money on the stabilization of per-capita vehicle-miles traveled, a trend folks like Robert Puentes at the Brookings Institution trace all the way back to 2000. Indeed, according to Puentes, per-capita VMT hit a plateau around 2000 and began dropping in 2005 — a trend that mirrors the overall trend in congestion as described by TTI.

How you diagnose what has happened over the last decade helps shape what you think should be done about America’s transportation problems in the future. TTI’s diagnosis is that as the economy comes back to life, congestion will rear its ugly head once more. Its solution: “more of everything.”

I’m not quite so sure. A constellation of factors — ranging from high oil prices to the aging American population to changing consumer preferences to the saturation of the American automobile market — could conspire to hold vehicle travel and highway congestion down in the years to come. Solving America’s transportation problems in that case becomes less of a matter of “more more more” and more of a matter of making the smartest investments that can both reduce congestion in the short term and build a resilient, efficient, environmentally sustainable transportation network for the future.

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.