The Road Ahead: Toxics

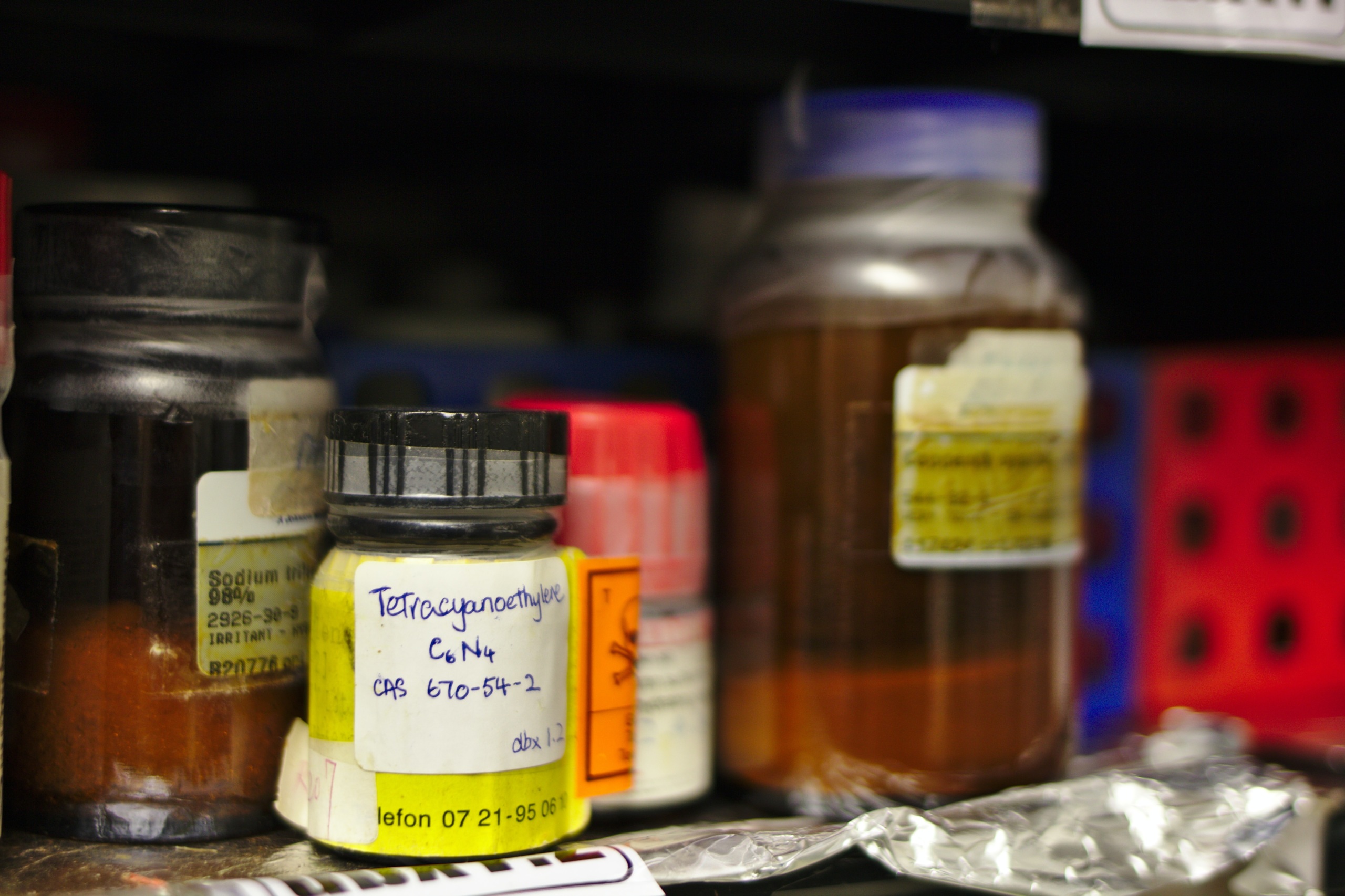

Americans are exposed to hundreds of chemicals on a daily basis. They are in our personal care products, our cookware, our furniture and our electronics. They are used on our lawns and on the crops that produce our food. They are also in our bodies.

Previous posts in the “Road Ahead” series:

The 2016 election has come and gone. President-elect Trump, members of Congress, governors and state legislators are now waking up to the fact that they are running the country and are planning their transition to power.

There is no better time to take a step back and take stock of where we are as a country on the issues that will shape our future. Over the coming weeks, Frontier Group analysts will be providing their take on the lay of the land on the issues on which they work.

Americans are exposed to hundreds of chemicals on a daily basis — in our personal care products, our cookware, our furniture and our electronics. They are used on our lawns and on the crops that produce our food.

They are also in our bodies. A recent Center for Disease Control (CDC) study found a chemical used in many plastics, bisphenol A (BPA), was present in the urine of more than 90% of participants. The same study found polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), a fire retardant used on many electronics, present in almost all of the study’s participants. The pervasiveness of these chemicals is cause for concern: BPA has been linked to decreased reproductive ability in mice, potentially indicating the same effects in humans, and PBDEs have been identified as a possible carcinogen and as having negative effects on child development and brain function.

Even chemicals that have been definitively proved harmful remain present in our day-to-day lives. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), once widely used as coolant in electronics and found in caulking and fluorescent lights, were banned for most uses by the EPA in 1979. However, school buildings built or retrofitted before 1979 may still house the chemical, meaning as many as 14 million American school children have potential continued exposure to PCBs. Traces of PCBs are found in soil where the compound lingers for years; they can travel long distances by air and have been found in the Arctic, and can be taken up in small marine organisms and fish, resulting in high levels of PCBs in the mammals that rely on fish as a primary food source.

The chemical industry has long been allowed to operate on the principle that chemicals are “safe until proven otherwise”. Because of the persistence of some chemicals and the ambiguous ways in which they can affect our health and well-being, public health advocates argue for applying the “precautionary principle” to the introduction of new chemicals – that is, demonstrating that new chemicals are safe before introducing them into the products we use and the environment we share. In reality, however, more than 80,000 chemicals are registered for use in the United States, and only a fraction of them have been tested by the EPA for a full range of health effects. The 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) limits the EPA’s ability to test potentially harmful substances, requiring proof of “unreasonable risk” before allowing the agency to run tests – evidence that can take many years to assemble.

In recent years, state governments have taken the lead in efforts to limit public exposure to dangerous chemicals. In 2014, California passed a bill requiring manufacturers to reveal if their products contained flame retardants and to publish that information online. Both Maryland and New York passed legislation banning the flame retardant TDCPP in children’s products. Vermont passed a bill that established a public list of high-concern chemicals and required manufacturers to replace those toxics with a safer alternative or be barred from sale in the state. In 2015, Oregon passed a similar bill to the Vermont legislation, and Minnesota passed a bill banning the sale of children’s products and furniture containing ten different toxic flame retardants.

Progress, however, had been much slower at the federal level, where the debate about reforming the Toxic Substances Control Act had been going on for decades with little to show for it. In June 2016, however, President Obama signed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act, the first major reform of federal toxic chemical laws in 40 years. The law eliminated language requiring the EPA to use the “least burdensome” method for addressing a substance’s risk, a provision that in a 1991 court case had impeded the EPA’s regulation of asbestos. The new law also explicitly called for the protection of vulnerable groups such as children, pregnant women, and workers in industries with heavy chemical use, and expanded the authority of the EPA to test new and existing chemicals in the market.

But these improvements in the law came at a harsh cost: the preemption of state regulation during a chemical’s safety assessment and following regulation of its use. This tradeoff –- losing states’ ability to pioneer new actions to protect the public, in exchange for somewhat stronger EPA authority — was a dubious one in good times. It looks particularly problematic as the avowedly anti-regulatory Trump administration takes office in D.C.

Over the next two years, we will see the EPA use (or not) its new authority under the law, states test the boundaries of what is possible under the new regulatory regime, and public health organizations continue to investigate and educate Americans about the growing range of toxic chemicals in our homes and our environment – and the consequences for our health. The future may be uncertain, but one thing is clear: the debate over when and how to safeguard the public from toxic chemicals is far from over.

Topics

Authors

Find Out More

What’s in that Pine-Sol bottle?

More and better testing would protect us from chemical threats

Chocolate cookies with a smidge of “forever chemicals”