Gideon Weissman

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

The following is an exerpt from the report Safe for Swimming?: Pollution at Our Beaches and How to Prevent It, by Frontier Group and Environment America Research & Policy Center. See the full report for sources, as well as information on national beach water quality.

Contaminated beach water can make swimmers sick. That is why communities across the country have undertaken efforts to tackle pollution.

Community efforts to protect beaches can take multiple forms: Installing green and natural infrastructure to prevent runoff from reaching the ocean; investing in sewage infrastructure to prevent sewage overflows; and working to stop pollution at its source, including by improving agricultural practices.

The following case studies are examples of these approaches paying off.

Green infrastructure at Bristol Town Beach in Rhode Island has helped mitigate runoff pollution and improve water quality. Staff photo.

Many existing roads, parking lots and other impervious surfaces that turn stormwater into runoff pollution are here to stay. But communities can take steps to prevent stormwater from flowing into waterways, including by installing “green infrastructure” that mimics some of the functions of lost natural areas, or by restoring or creating new natural areas.

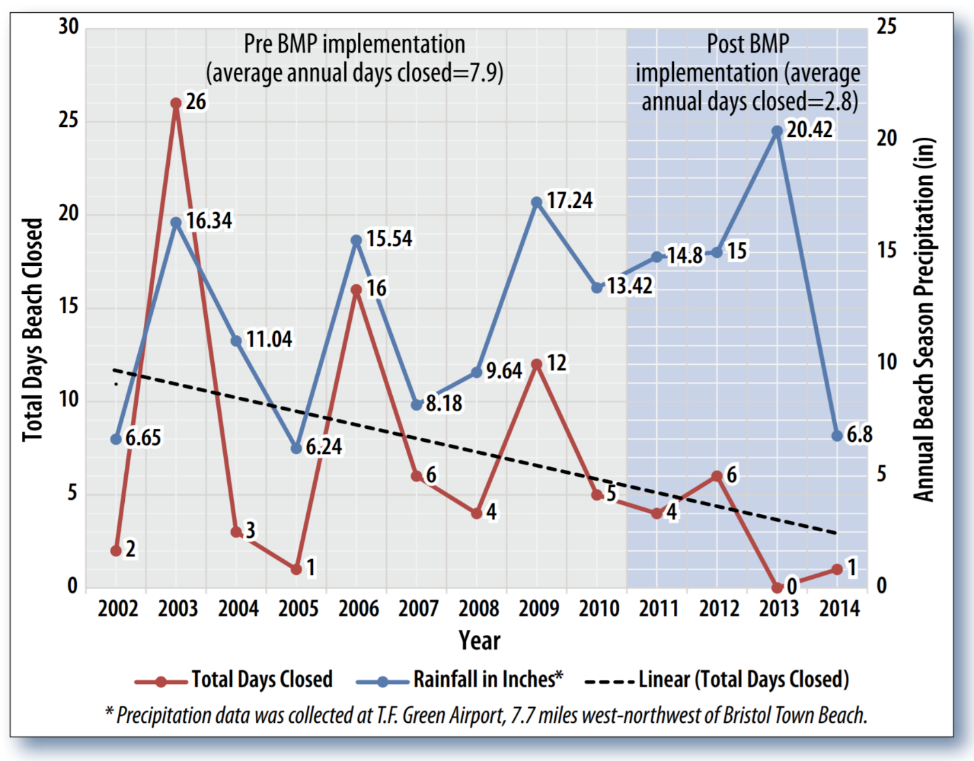

Bristol Town Beach along Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay was closed on average eight times per swimming season between 2002 and 2010 as a result of exceedances of the state’s single-sample bacteria standard. At fault was runoff pollution, including runoff from a nearby suburban neighborhood which discharged through stormwater outfalls just north of the beach.

A water quality improvement plan was developed through a collaborative effort between the town of Bristol and state and federal partners, including the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and the U.S. EPA. The plan primarily involved the installation of green infrastructure at the beach: drainage swales, permeable pavement, tree plantings, and a vegetative treatment system, which is an area of permanent vegetation designed to catch and treat runoff pollution. Green infrastructure is a proven solution for reducing the impact of runoff pollution. In addition to being able to capture and filter runoff pollution, green infrastructure can bring aesthetic and recreational value to beaches and urban landscapes.

Following implementation of the plan, exceedances of the state’s water quality standard dropped sharply. In 2013, Bristol Town Beach had zero closures, despite a ten-year high in rainfall.

This EPA chart shows how at Bristol Town Beach in Rhode Island, beach closures declined following the implementation of best management practices (BMP) including the installation of permeable pavement and planting of trees. Credit: EPA

Improved sewer infrastructure and other efforts to reduce pollution have dramatically improved water quality at Avalon Beach in California. Credit: Tom Gally via Wikimedia (public domain)

Aging, leaky sewage systems can create near-constant pollution problems, making water unsafe for days or weeks at a time. In its 2017-2018 Beach Report Card, Greater Los Angeles environmental group Heal the Bay shined its “Beach Improvement Spotlight” on one community that invested in sewer improvements and saw dramatically improved water quality: the city of Avalon, on Catalina Island 20 miles off the coast of Los Angeles.

For years, water quality at Avalon Beach had suffered from sanitary sewer overflows, caused by both maintenance problems and operator error. The overflows created health risks, including for the people who use the beach for swimming, fishing and diving. Pollution problems landed Avalon Beach on Heal the Bay’s “Beach Bummer List,” for beaches with poor water quality, 12 separate times.

The city began turning its pollution problem around in 2012. That year, the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board established a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for the city of Avalon with numeric limits for bacteria concentrations, including for enterococcus and fecal coliform.

To meet the new limits, the city of Avalon spent $5.7 million on sewer main improvements and implemented a new sewer inspection and tracking system. Sewer improvements included the rehabilitation and replacement of aging sewer lines, system-wide cleaning, and root control. The city also took steps to reduce other sources of water pollution, including adopting a regulation to prohibit restaurants and businesses from discharging or dumping debris, and developing a pollution prevention public education program.

Following these steps, Heal the Bay reported steady improvements in water quality – and Avalon Beach has not appeared on the “Beach Bummer List” since 2013.

The Wilson River in Oregon is used for swimming and boating. It is also the largest river feeding the Tillamook Bay, a picturesque bay popular for kayaking and crabbing. Despite the beautiful setting, both the river and the bay have long experienced elevated levels of fecal indicator bacteria.

To clean up the river, local environmental and academic organizations formed a plan that began with research to determine the source of the river’s fecal contamination. Beginning in 2001, a three-year research collaboration between the Tillamook Estuaries Partnership (TEP) and Oregon State University used bacteria genetic markers to establish that cattle from dairy pastures were a primary contributor to bacteria in the lower Wilson River. Improving water quality, therefore, would require reducing the impact of local agriculture.

Many of the farms in Tillamook County raise cattle on pasture. Such farms generally cause far less pollution than densely-packed cattle feedlots, which generate excessive manure that cannot be properly handled. Yet pasture-based farming can still threaten water quality if cattle and manure are not managed properly.

The TEP, along with the Tillamook Bay Watershed Council and Tillamook Soil and Water Conservation District, worked with local stakeholders to establish a set of measures to protect the river. These included fencing to keep livestock away from riverbanks, planting trees along the river, and acquiring a section of wetland to be maintained as a permanent natural area.

TEP also started the Backyard Planting Program, a voluntary program to help landowners plan and implement riparian vegetation projects. The program provided site-specific plans, a planting crew, and site maintenance, all for no cost. In its 2015, TEP reported that 116 landowners had participated in the program, including 48 agricultural landowners. Tens of thousands of native trees and shrubs have now been planted through the program.

In addition, the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture, worked with dozens of dairy farms throughout Tillamook County to improve manure management and reduce overapplication of manure on fields.

These efforts have helped create a cleaner river and have contributed to improvements in the health of the bay. In 2016, the state’s Conservation Effectiveness Partnership reported that river bacteria levels “now consistently meet the recreational use water quality standard.”

Top image credit: U.S. National Park Service

Former Policy Analyst, Frontier Group