How Transit Pays for the Automobile’s Sins

Over and over again, we call on transit to compensate for the failures of cars. But there is a cost to correcting these failures, and all of them wind up on the “transit” side of the ledger.

Cross-posted from Streetsblog.

An op-ed in Friday’s Washington Post by three professors of urban planning rained on the parade of transit advocates celebrating a new 57-year high in transit ridership. Ridership, the authors wrote, has actually fallen on a per-capita basis since 2008 (as has driving, by the way), as well as outside of New York City.

To underscore their point about transit’s unimportance outside of NYC, they wrote, “[t]ransit receives about 20 percent of U.S. surface transportation funding, but accounts for 2 percent to 3 percent of all U.S. passenger trips and 2 percent to 3 percent of all U.S. passenger miles.”

If you are a transportation nerd like me, you have probably seen this kind of comparison before. It is a long-time favorite of transit denigrators, and for good reason: It makes transit look really bad.

But here’s the thing. Comparing spending on transit with spending on highways per trip or per mile is an inherently misleading exercise. In part, that is because it fails to recognize an important fact: Much of the transit service we provide in the United States is designed specifically to cover for the failures of our lavishly subsidized car-centered transportation system.

Here’s an example. In 2012, U.S. transit agencies spent $3.5 billion to provide “dial-a-ride” demand response service for the disabled — accounting for 9 percent of all spending on transit operations nationwide. Those services carried 106 million passengers, 1 percent of all transit riders.

That same year, Boston’s transit agency, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, moved nearly four times as many passengers as dial-a-ride at less than half the total cost.

What does that comparison tell you about the relative value to society of dial-a-ride versus the “T”? Or about the wisdom of spending an additional dollar on improving transit service for the disabled versus spending it, say, on running an extra train on Boston’s Red Line subway?

Not much, really. While dial-a-ride and the Red Line both fall under the umbrella of “transit,” they are very different services designed to serve very different needs. Comparing them on the basis of dollars spent per trip isn’t exactly like comparing apples to oranges, but it is certainly like comparing Macintoshes to Granny Smiths. The same is true of comparing transit to highway spending.

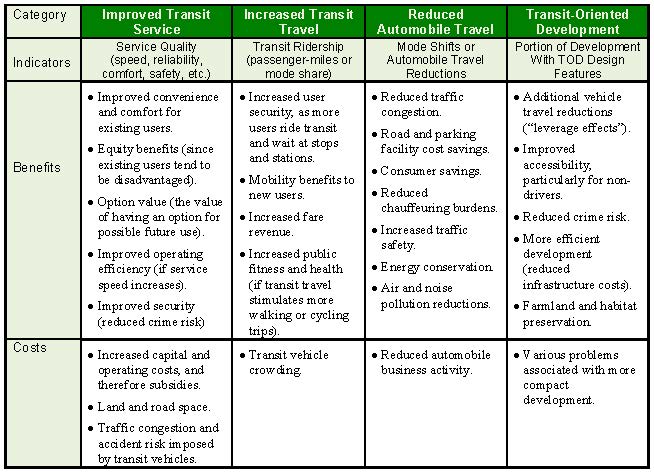

What really matters in evaluating whether we’re spending too much, too little, or just the right amount on a particular form of transportation is whether the benefits of those investments exceed the costs. As Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute has documented [PDF], public transportation delivers a wide range of benefits — including valuable benefits to drivers – that are often left out of the conversation. (The table below, from the VTPI report, Evaluating Public Transportation Benefits and Costs, gives some idea of what a more holistic picture of transit benefits and costs looks like.)

But there is another reason why this type of comparison is misleading. We need services like dial-a-ride mainly because our car-oriented transportation system often leaves disabled Americans — not to mention the poor, the elderly and those too young to drive — waiting by the side of the road.

Over and over again, we call on transit to compensate for the failures of cars. Need to get New Year’s Eve revelers home without killing each other on the roadways? Extend transit service hours, put more buses on the road, and make them free. How about getting large crowds of people to a festival or a big game without triggering gridlock? Provide shuttle buses or run extra trains.

These are smart choices. But there is a cost to correcting these failures, and in the crude accounting done by folks such as the Post op-ed writers, all of them wind up on the “transit” side of the ledger.

It’s a nifty trick, really. Design a transportation system that leaves a wide swath of the population unserved and tends to fail when you need it most (including pretty much every weekday morning and evening in most American cities). Call on transit to fill the gap, sometimes at great expense. Then tar transit as being the inefficient user of public funds.

The Post op-ed writers are correct that transit is far from meeting its full potential for getting cars off the road. But they fail to account for the fact that much of the money we currently spend on transit is intended for different purposes entirely: either to provide mobility to those left behind by our historical over-investment in highways, or, in some cases, to get certain cars off certain roads at certain times of day.

There are more and more American cities, however, where transit is doing more than filling in the holes left behind by our highway system. Cities are increasingly recognizing that transit investments — when made alongside smart land-use decisions and support for other transportation options — can expand the number of Americans with the option of pursuing car-free or car-light lifestyles. As Eric Jaffe notes in the Atlantic Cities, there are U.S. cities in which transit usage is indeed increasing steadily, and those cities might hold lessons for how we can increase ridership overall.

Increasing the cost of driving, the Post op-ed writers’ preferred solution to our transportation challenges, can help support the growth of car-free and car-light lifestyles. Recycling misleading statistics to denigrate transit’s complex but important role in our transportation system, on the other hand, is only likely to set us back.

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.