Electric vehicles are here. Now we need the infrastructure.

Electric vehicles have arrived. And not a moment too soon.

Through the first six months of this year, automakers sold nearly 300,000 plug-in electric vehicles (battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids), putting 2021 on pace to smash the previous record of 328,000, set in 2018.

As the upcoming 2021 edition of our annual Renewables on the Rise report (out next week!) shows, EVs have become both dramatically cheaper and more capable over the last decade. And with dozens of new electric vehicle models on the way, of all shapes, sizes and capabilities, the future of EVs looks bright.

That’s good news for our air and the climate. Electric motors are vastly more energy efficient than internal combustion engines and can be run on electricity from an increasingly clean grid powered by renewable energy sources. Electric vehicles are not an environmental panacea – manufacturing them takes energy and materials that contribute to climate change and other environmental problems – and they do not begin to solve the broader challenges with our transportation system. But when it comes to climate change, every fossil fuel-fired vehicle that is removed from the road is one step toward a healthier future.

There is just one problem – and it’s a big one: Getting clean electricity into our nation’s growing fleet of EVs.

The U.S. is woefully short of the public charging infrastructure we will need to make traveling in an EV as convenient and seamless as traveling in a gasoline-powered car. And as we documented a few years ago, much of the public charging infrastructure we do have is difficult, expensive or inconvenient to use.

Nowhere is the challenge bigger than in cities. In 2018, my former colleague Alana Miller wrote our report Plugging In, which predicted that cities around the country would soon be inundated with electric vehicles that, at the moment, have no good place to recharge. One-third of American housing units don’t have a garage. Residents of big cities who live in multifamily buildings or even in single-family homes without their own driveways generally lack the ability to plug their cars in overnight at home. Since experts expect most EV charging to take place at home, that creates a potential problem – one that could either slow the uptake of EVs in urban areas or leave EV owners frustrated – in the absence of robust public charging infrastructure.

As Slate’s Henry Grabar wrote last week, the problem of providing electric vehicle charging in cities is far from solved. Not only that, but solving it is complex, involving fraught and potentially costly decisions about what kinds of charging infrastructure to install where. Moreover, the question of where to locate chargers aggravates already contentious debates about the highest and best use of valuable curb space – one that pits parking for cars against bike lanes, bus lanes, “streateries,” delivery zones and other beneficial uses of a scarce resource.

Nor is providing public charging to cars and light trucks the only infrastructure issue bedeviling the transition from gasoline-powered cars to electric vehicles. In early October, I took part in the Asilomar Biennial Conference on Transportation and Climate Policy sponsored by the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. A consistent theme of the conference – regardless of whether the topic was light-duty, medium-duty or even heavy-duty vehicles – was that, when it comes to electrifying transportation, the vehicles are here. The infrastructure is not.

Getting utilities to deliver enough power to fleet depots and banks of DC fast chargers to allow them to deliver an adequate charge in a reasonable period of time is proving to be a huge challenge – and, in some cases, a significant expense. At the same time, getting charging networks to “work” for ordinary consumers is also a big issue – with significant effort needed to make charging networks interoperable, ensure reliable operation and 24/7 public access to chargers, and create transparent pricing and billing systems.

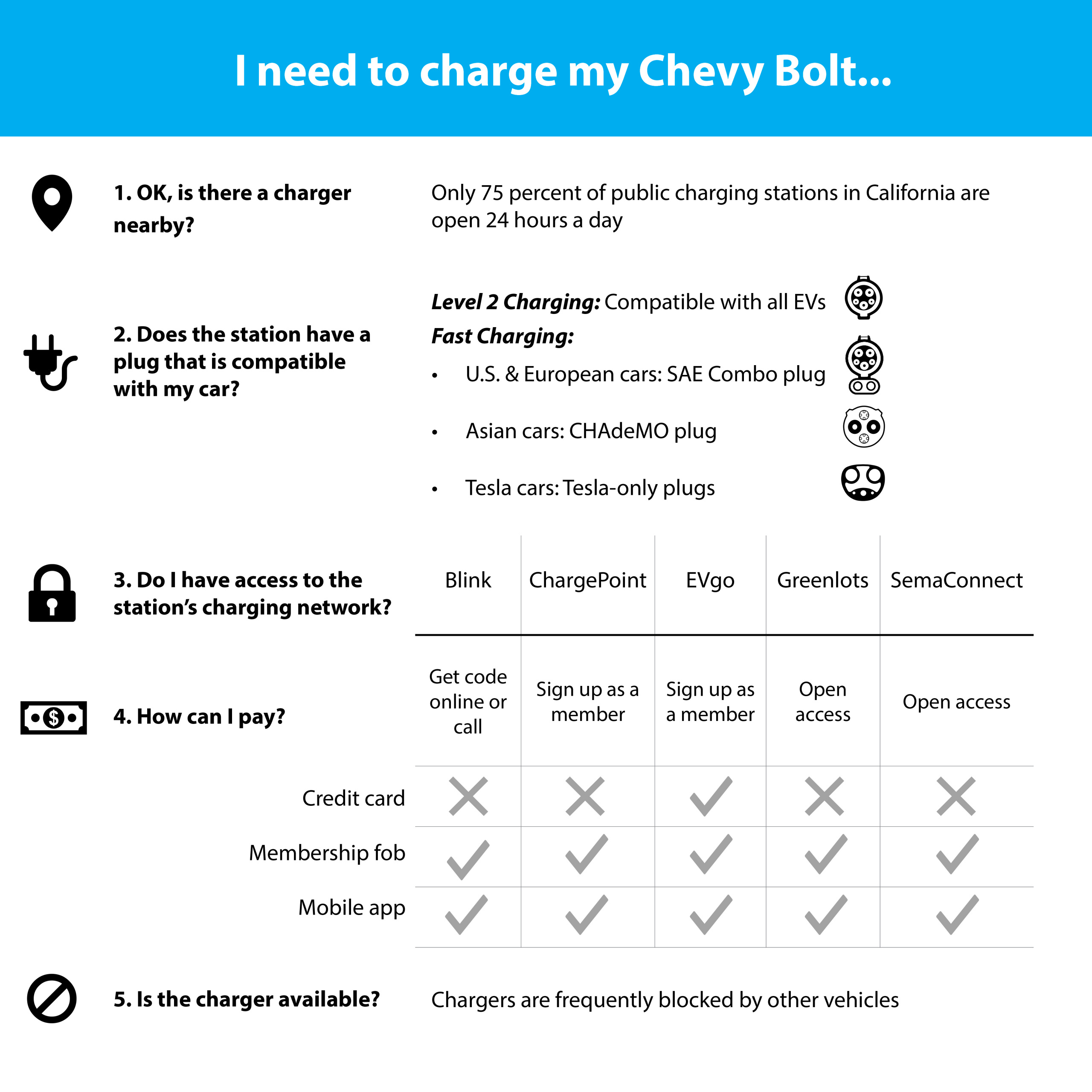

Charging an EV can be a challenge. (From “Ready to Charge“, 2019.)

The good news is that the federal government appears poised to get involved, an essential and appropriate step to reassure Americans living anywhere in the country that traveling in an electric vehicle is a viable option. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework currently being debated in Congress includes $7.5 billion in investment in EV charging, which will help to achieve President Biden’s goal of installing a half-million charging stations nationwide by 2030.

But regardless of the amount of money flowing into EV charging, much of the real work of making EVs function well in our cities and towns will be done at the state and local level. Today, we joined with Environment America Research & Policy Center and U.S. PIRG Education Fund to release a new toolkit for local governments, chock full of tangible, on-the-ground steps that local residents and policymakers can take to make their cities and towns more EV friendly. The report also highlights steps that leading local governments all across the country have already taken to expand access to charging, expedite permitting, advance government purchases of EVs, educate the public about the benefits of EVs, and much more.

Over the last century, vast amounts of money have been poured into building out the infrastructure that turns a barrel of oil pumped from the ground in Saudi Arabia into gasoline flowing from a pump in your neighborhood. Breaking free of our dependence on fossil fuels will require us to build a new infrastructure that is cleaner and better. With investment from the federal government and hard work from state and local governments, citizens, businesses, and electric utilities, we can build out the infrastructure that will enable us to power our vehicles and our lives with clean, renewable energy. But there is no time to waste, and we need to start now.

Photo: Alana Miller

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

The gas tax is a tax like any other. We need to start treating it that way

Counting the hidden cost of driving

High gas prices are a symptom of our dependence on oil. It’s time to cure the disease.