Who Are You Going to Believe: The Government’s Data or Your Sore, Watery Eyes?

I live in Santa Rosa, not far from several of the fires that have been burning in Sonoma County. This past week, the official measurements of air quality – data from air quality monitoring stations that post real-time information to the airnow.gov website – haven’t matched what my family and I have been experiencing. This wouldn’t matter much if the problem cropped up only during temporary events like fires, but it happens regularly in other communities that have constant sources of pollution nearby.

I live in Santa Rosa, not far from several of the fires that have been burning in Sonoma County. This past week, the official measurements of air quality – data from air quality monitoring stations that post real-time information to the airnow.gov website – haven’t matched what my family and I have been experiencing. This wouldn’t matter much if the problem cropped up only during temporary events like fires, but it happens regularly in other communities that have constant sources of pollution nearby.

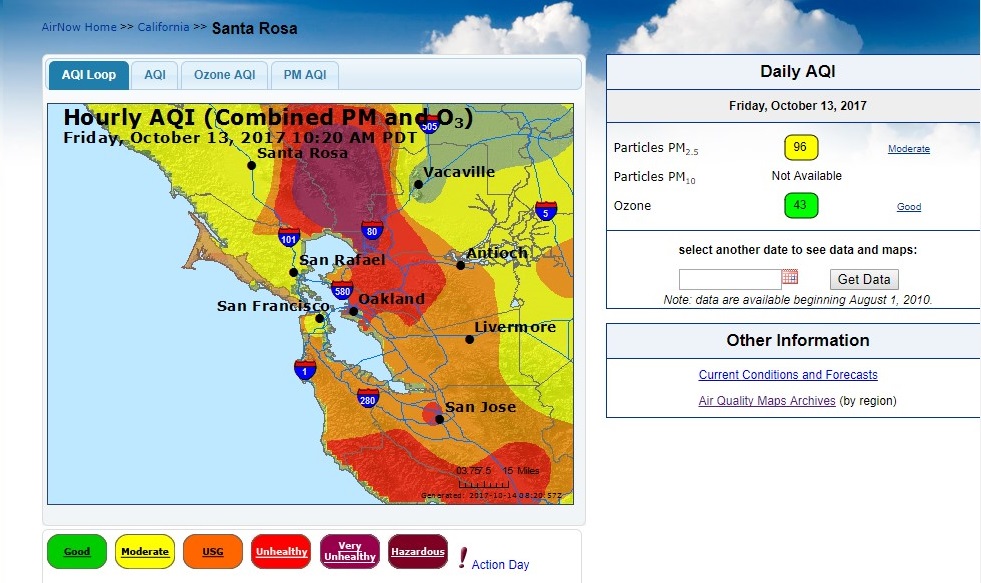

Here’s one example of how I experienced the problem of reported air quality not matching what was happening on the ground. Last Friday, smoke was so thick in our neighborhood that I could see it when I looked across the street. My son and I decided we needed to wear face masks to walk down the street to tend to a neighbor’s house. Yet the real-time air quality data posted on the nation’s official reporting site, airnow.gov, said that air quality in Santa Rosa was “moderate,” shown in yellow in Figure 1 (Santa Rosa is top center of the map).

Figure 1. Air quality map from Friday, October 13

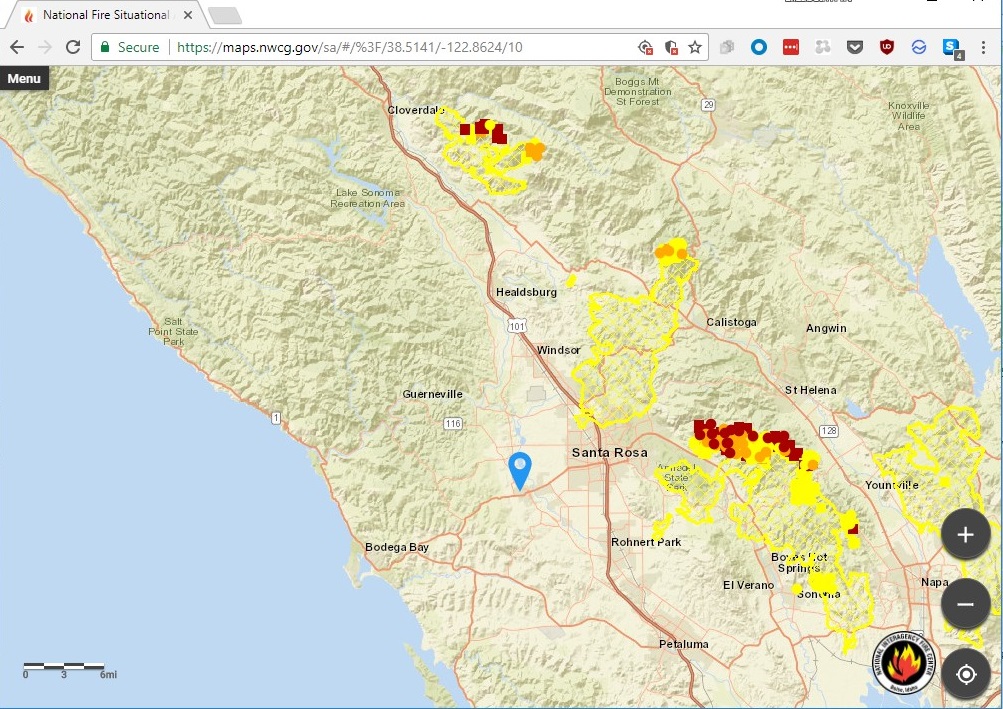

The pollution hotspot in my neighborhood was undetected because Sonoma County has a single air quality monitor, located in Sebastopol, about eight miles west of Santa Rosa. Normally, this is adequate for the county, which has relatively clean air and few major polluters. However, the fires have created intense pollution hotspots and air quality isn’t uniform. (Figure 2 shows the approximate location of the air pollution monitor relative to the fires.)

Figure 2. Sonoma County’s single air pollution monitor is located at the blue pin, miles to the west of the fires

The blue pin marks the location of Sonoma County’s single air pollution monitor. Fires are outlined in yellow, and the active edges of the fires on Monday morning are shown in orange and red dots. Sonoma County includes most of the area between the ocean and the eastern edge of the fires.

The problem of undetected pollution hotspots isn’t limited to wildfires. As we discussed in our April 2017 report, released with Environment America Research & Policy Center, that documented air quality problems across the U.S., in regions of the country with ongoing pollution hotspots created by highways, airports and industrial facilities, air quality monitors are too dispersed to accurately report local air quality conditions. This limits the ability of public health officials to address these chronic threats to the well-being of people who live, work and study nearby.

Gaps in the monitoring network are apparent in a variety of locations.

- In Pittsburgh, industrial facilities and major roadways, especially those carrying diesel vehicles, create areas of elevated pollution. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University repeatedly sampled air quality at 70 sites across Allegheny County, in the heart of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, and detected large variations in levels of nitrogen dioxide and black carbon, a type of particulate matter.

- On days with higher air pollution from major California airports, more people living nearby go to the hospital for care. They experience more health problems than would be expected based on regional air pollution data.

- The advent of industrial-scale fracking operations in south Texas’ Eagle Ford region created a new pollution source in the mid-2000s, but existing air quality monitors were located on the periphery of the region. Residents weren’t able to learn about the extent of the air pollution until an air quality monitor was installed in 2015 in the middle of the fracking area.

Undetected pollution hotspots potentially affect millions of Americans. More than 11 million Americans live within 500 feet of a major highway. Pregnant women who live closer to traffic-related air pollution are more likely to give birth to small babies, while children directly exposed to traffic pollution develop respiratory problems, including cough, wheezing, runny nose and asthma.

Understanding the health risks of air pollution requires that we have better knowledge of where pollution is most concentrated and who is exposed. That likely will involve installing more air pollution monitors and better modeling of how pollution disperses from specific sources. State environmental agencies, which operate air quality monitors, could add to their permanent network of monitors or could partner with researchers and companies that have begun to install air pollution monitors on cars that map and photograph city streets. Mobile pollution detection vehicles could be deployed in the wake of fires or other unusual pollution events to provide residents with better information about pollution hotspots.

Better data about where pollution lingers is crucial to evaluating measures to further reduce pollution from cars, trucks, power plants and industrial facilities. Targeted pollution control measures would reduce pollution hotspots and provide year-round improvements for people who spend time in those areas.

More air pollution monitors won’t improve air quality in Santa Rosa right now, but they would give residents the knowledge they need to protect the health of themselves and their families as we begin to recover from the fires that have devastated our community.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

School air monitoring: A win for public health

How much does American driving contribute to global climate pollution?