Shimon Schaff

Intern

What does “human error” really mean? And what is the role of automated vehicles in protecting us from it? These are important questions to clarify if we are going to get the greatest safety benefit out of AV technology.

Intern

This blog post is contributed by Frontier Group intern Shimon Schaff, a senior at Tulane University majoring in environmental studies and international development.

Despite the recent hype, the concept of automated vehicles (AVs) seems like a farfetched and futuristic idea to much of the American public. Many feel hesitant about surrendering the driving task to a piece of software and trusting it to get them from place to place safely.

Supporters of automated vehicles cite the widely used statistic that 94 percent of vehicle crashes are due to “human error.” Ads from the Coalition for Future Mobility, which is an association of automotive, technology, and policy groups, read:

Human error. According to government data, it’s a factor in 94 percent of all crashes. And it’s taking a growing number of lives after decades of decline. So imagine how much safer our roads would be with Autonomous Vehicles.

But what does “human error” really mean? And what is the role of AVs in protecting us from it? These are important questions to clarify if we are going to get the greatest safety benefit out of AV technology.

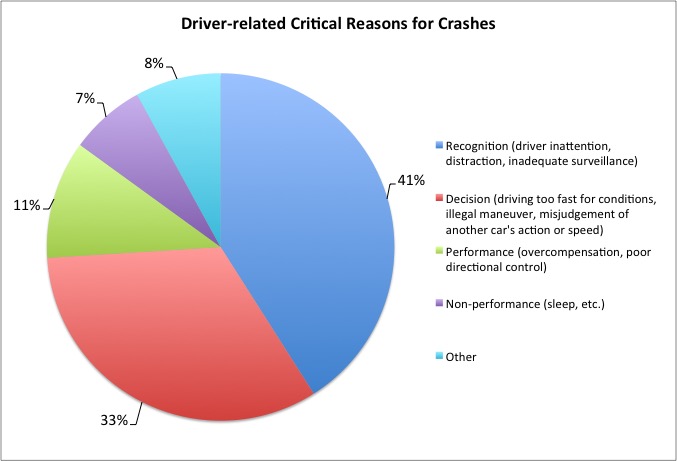

To start, let’s unpack the 94 percent statistic, which comes from the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey (NMVCCS) by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). According to the study, “the critical reason, which is the last event in the crash causal chain, was assigned to the driver in 94 percent of the crashes.” Elsewhere, the NHTSA’s website states that “94 percent of serious crashes are due to human error.”

Data: NHTSA, Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey, 2015

When I hear the word “error,” I think of it as equivalent to “mistake” or having an unintentional nature. But many of the serious crashes attributed by the NHTSA to driver error weren’t the results of mistakes at all, but rather of intentional choices made by a driver.

Over one quarter of road deaths in 2016, for example, were attributed to speeding (10,111 fatalities). Additionally, the NMVCCS estimates that 3.8% of driver-attributed crashes are due to illegal traffic maneuvers. For example, in 2016, 811 people were killed in crashes involved in red light running. Finally, 10,497 traffic deaths in 2016 involved drunk driving.

What would the conversation about AVs be like if we shifted away from ambitions to prevent all “human error” and toward deploying technology that can eliminate specific behaviors that are costing lives right now – such as lack of compliance with traffic laws?

Legislation or policy requiring AVs to be designed to follow traffic laws would seem to be a sensible and effective safety measure and could provide immediate lifesaving benefits, even before full automation. There is little reason to wait for the deployment of a fully capable “Level 5” automated vehicle that is able to drive everywhere on its own before considering such a step.

Further, how might we think differently about governing AVs if we considered the new sorts of error that might be introduced in the design of AVs? AVs still have a driver, but that driver is software rather than a human. So, while AVs may remove human error, they do not necessarily remove all forms of driver error, including errors in judgment.

Emerging areas of concern with AV technology include both the ability of AVs to detect and react to pedestrians and bicyclists as well as cybersecurity. With AVs, it is critical that the driving software doesn’t get hacked or malfunction, as this would pose serious threats to passengers in transit.

I believe that AVs have real potential to benefit road safety. But it is important to ensure that the transition to automated vehicles happens in ways that maximize the benefits to the public. This means applying AV technology in ways that can be immediately helpful in protecting the public, and ensuring that, when fully autonomous vehicles do come online – whenever that may be – we don’t replace driver error with other avoidable dangers.

Photo: Cruise Automation Chevy Bolt in San Franscisco, Wikimedia user Dllu, made available under Creative Commons license CC-BY-SA 4.0

Intern