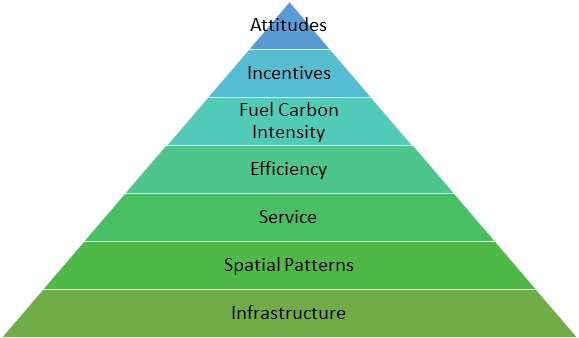

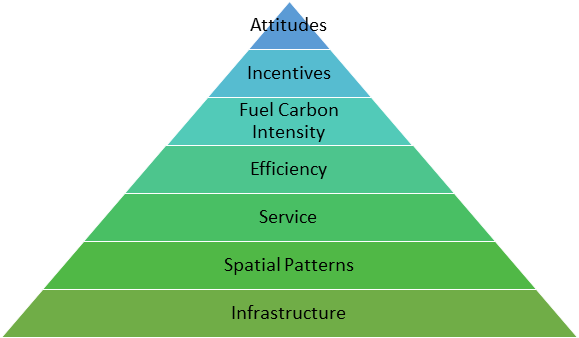

The Transport Decarbonization Pyramid

Building a zero-carbon transportation system isn’t as simple as picking enough options off of a policy “menu” to meet a particular emission reduction goal – rather, policies react with, complement or compete with one another in complex ways. The solution lies in applying the right combinations in the right places at the right times.

Note: I started this post in the fall of 2017 and shelved it a couple of months later. I felt less than rock-solid about the theory and it felt like somebody, somewhere in the literature had to have done something like this before. The investment of time needed to address those issues seemed overwhelming.

Fast forward to today and more people are talking seriously about how to decarbonize transportation than at any time I can remember. Which is great! But much of that talk is in the form of (in my view) pointless argument about whether one or another technology or approach should prevail. This post attempts to provide a framework for understanding why we need a comprehensive approach, and why going all-in on a single strategy – whether it be electric vehicles, buses, bikes or what have you – is choosing to fail.

It is said in statistics that all models are wrong, but some are useful. My purpose in sharing this post now is not to assert that it is right in all the particulars, but in the hopes it might prove useful. -Tony

America’s transportation system is the nation’s biggest source of the carbon pollution that is causing the globe to warm. There is no solution to dangerous global warming that does not include dramatic change in how Americans get around.

How should we go about making that transformation happen?

A couple of years ago, I suggested on this blog that the conceptual model that has long shaped our thinking about policy about climate change – the “stabilization wedges” model – was a poor fit for the transportation sector.[1] Building a zero-carbon transportation system isn’t as simple as picking enough options off of a policy “menu” to meet a particular emission reduction goal – rather, policies react with, complement or compete with one another in complex ways. The solution lies in applying the right combinations in the right places at the right times.

So, we need a better conceptual model. To follow is a first, very rough stab at one.

We might think of carbon emissions from transportation as being determined by factors we can arrange in a pyramid, like this:

Working from the bottom up:

- Infrastructure creates the potential for travel. If there are no roads, no airports, no ports, there is no way to get much of anywhere.

- The spatial patterns of people and destinations determine the potential demand for travel – how far and how often people feel compelled to travel to meet their needs.

- The quality or value of service provided on a piece of transportation infrastructure – in terms of cost, frequency, convenience, speed, safety – shapes the degree to which that piece of infrastructure will actually be used for travel.

- The efficiency of the service – both the number of people moved per vehicle and fuel efficiency of the vehicle – determines the energy intensity of a given mile of travel.

- The carbon intensity of the fuel, along with efficiency, determines the carbon intensity of a mile of travel.

- Incentives, in the form of tax breaks, subsidies or non-monetary incentives, influence individuals to choose one set of available transportation and lifestyle options over another.

- Attitudes or preferences determine how an individual will choose to travel, given an available set of options.

Thinking about the challenge this way lead to a series of ideas about how best to approach the task of decarbonizing transportation.

10 Propositions for Transport Decarbonization

1) The ability to make change at the top of the pyramid is constrained by conditions toward the base of the pyramid.

Think about a person who wants to ride a bike to the store instead of driving. No matter how strong their preference for riding, they may choose not to ride if they face disincentives (subsidized driving), inefficiency (a lousy bike), poor service (danger on the road), or an unfriendly spatial pattern (no store within biking distance). The same is true of other entities; for example, a city that prefers to expand transit service might find itself unable to launch a viable service in a sprawling suburban area.

Blaming individuals for failing to make low-carbon transportation choices that the system makes difficult or impossible is not useful. Yes, we could all drive less than we do, and we should all make an effort to do so. But the ability to drive meaningfully less – on the scale needed to make a significant dent in carbon pollution – depends on being in a place where other options don’t require a tremendous sacrifice of time, money or personal safety that most people just trying to get through their daily lives will be hesitant to make.

Similarly, assuming that individuals’ current transportation behaviors are pure expressions of free will – thereby validating the status quo and limiting the horizon of conceivable change – is flat-out wrong. We are all products of our surroundings, shaped by deliberate policy decisions of the past, including decisions made by people who died before we were even born. If we want to encourage large numbers of people to act differently, we need to not only make new policy commitments based on the priorities of today, but also, in many cases, take action to repair the damage of bad decisions of the past.

2) Market forces, culture and public policy are capable of changing conditions at any point in the pyramid.

Let’s go back to our would-be bike shopper. If she wanted to change the conditions that limit her ability to bike, what might she do? She might get together with her local bicycle club and organize a Critical Mass-style group ride to the store, achieving safety through numbers and making it cool to shop by bike (culture). Or she might lobby her city councilor to create a bike path (policy). Or she and enough others might create demand for a grocery store closer to her home with a bike rack or bikeshare station outside (market).

Similarly, increased demand for electric vehicles might create demand for more public charging infrastructure, met either by private companies or by the public sector.

3) Changes at the base of the pyramid are the most profound, impactful and lasting. Changes at the top of the pyramid are quickest, but also most ephemeral and difficult to scale.

If you want to reduce carbon emissions from transportation today, offer someone a ride to work. If you want to reduce emissions tomorrow, provide donuts for carpool-to-work day. If you want to reduce emissions three years from now, provide electric vehicle charging at the workplace. And so on.

Winning strong land use policies could take years, and building out the ensuing walkable neighborhoods could take decades. But at the end of that process, you won’t need to spend money on donuts every week to convince people to do something that has become natural and easy.

4) The most important effect of changes in attitudes and preferences is not on short-term behavior but on culture, market demand and public policy, which can alter conditions at the base of the pyramid.

The desire to, say, live in a walkable neighborhood in a city with good public transportation can only be expressed if the option actually exists in a real place at a price an individual can afford. It is only when changes in preferences gain sufficient momentum to change conditions at the bottom of the pyramid – through culture, markets and/or policy – that a critical mass of people will be able to adopt lower carbon transportation behaviors. YIMBYism, for example, is a political phenomenon that would have been difficult to imagine even a decade ago, resulting from, among other things, shifts in preferences for urban living and broader economic forces. Those changes in preferences may be ephemeral (though I doubt it), but public policy shifts they create will have impacts for years and decades to come.

Cultural change in institutions – such as the replacement of a generation of auto-centric transportation planners with those with a multimodal approach, or an evolution in the views of corporate executives on what makes for a good headquarters location – can change conditions even without outward changes in policy. But achieving change in this way takes time.

5) Climate science suggests that it is currently necessary to advocate for changes at all levels of the pyramid at once.

The persistence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the existence of climate tipping points suggest that urgent, short-term efforts to reduce emissions are critical, while the need to obtain near-zero carbon pollution by 2050 suggests that fundamental changes that take place over longer time scales are necessary. We need to both work on short-term, top-of-pyramid changes and long-term, base-of-pyramid changes at the same time. Twenty-five years ago, we might have had the luxury to choose. Now we don’t.

So, we need to replace “either/or” with “both/and”. We need to electrify vehicles and to build communities where driving is not necessary. We need to institute decongestion pricing and to increase transit options for those looking for alternatives. We need to envision solutions that work for cities and for suburbs and for rural areas, since we’re likely to have all of them in something like their current form for decades to come.

Pitting solutions against one another is counterproductive. We need them all. And we need to be creative in envisioning how different solutions – and the people who advocate for those solutions, regardless of their level of concern about the climate – can best complement one another to achieve transformative change. Every synergy we can create, every bit of pointless infighting we can avoid, is a bit of extra fuel propelling our effort toward a zero-carbon transportation system.

6) Failing to change conditions at the base of the pyramid makes every effort to achieve decarbonization further up the pyramid more difficult and costly.

Even if you could choose to focus all your energy on achieving change at the top of the pyramid – leaving sprawl, “car culture” and the like untouched – doing so would create other difficulties.

You might, for example, seek to eliminate carbon pollution from transportation through electrification alone, while maintaining infrastructure and land-use patterns that breed car dependence. But doing so would require far more investment in charging infrastructure, vehicles and electricity generation, while also leaving important co-benefits of reduced car dependence on the table.

The same is true of carbon pricing. Yes, you could theoretically set a carbon price high enough to force a dramatic shift in personal behavior in the short run and reset market incentives to shift conditions at the base of the pyramid over time. But it would neither be politically easy to create such a carbon price nor easy to sustain it amid the political backlash it would likely engender.

Moreover, a smart approach to decarbonization would argue for hedging one’s bets – pursuing change in a wide variety of areas in the event that change in one area fails.

7) Stopping backsliding at the base of the pyramid is as important as winning ephemeral victories at the top, and represents a largely missed opportunity for climate activism.

Building new carbon-intensive infrastructure or development today casts a shadow that stretches decades if not generations into the future. If the United States must decarbonize its transportation system by mid-century, we cannot afford to build long-lasting, high-carbon transportation infrastructure now that will eventually become a collection of stranded assets.

Climate activists have figured this out when it comes to fossil fuel transportation infrastructure such as the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines. We haven’t yet figured it out when it comes to boondoggle highway projects with a heavy carbon footprint. For better or worse, America’s policy system creates many opportunities to stop things. Stopping carbon intensive infrastructure is a critically important but oft-neglected strategy for long-term change.

8) Taking advantage of untapped potential at the base of the pyramid provides an opportunity for near-term progress.

America has walkable neighborhoods, transit lines and other infrastructure to support low-carbon infrastructure that we simply do not use. During the last half of the 20th century, we allowed cities with good urban “bones” (many of them in the Rust Belt) and thousands of traditional, walkable small towns to fall into decay and disrepair. Much of the infrastructure of those communities remains, its potential for sustaining lower-carbon lifestyles squandered. Similarly, America possesses transit and rail lines on which we fail to provide adequate service or along which we fail to accommodate compact, transit-supported development. Decarbonizing transportation will require building new things, but also reclaiming old things and old ways of being that allowed us to spend less time in travel.

9) Prerequisites matter.

Electrifying vehicles is an important thing to do even if the electricity used to power them today comes 100% from coal. Why? Because changes lower down on the pyramid are often prerequisites for future changes closer to the top. Electric vehicles can be powered by zero-carbon energy; gasoline powered vehicles can’t. So, putting EVs on the road today opens a door for emission reductions five or 10 years down the road that we are going to need to meet our goals. In some cases, temporary increases in emissions are a worthwhile price to pay to maintain the potential for substantial decreases in the long run.

10) Effective action can occur at any scale.

Eliminating carbon pollution from transportation will require a national response. But the same principles described above apply to action at the local and state levels as well. Every incremental step at a local level makes change at a higher level more achievable. E.g., the more people in an area who travel in low-carbon ways, the less political opposition there will be to measures to price or constrain high-carbon travel.

Any or all of these propositions can be – and probably will be – contested. Taken together, however, they add up to something close to a holistic way of thinking about the problem and a set of principles to guide action.

For years, climate advocates have focused a great deal of energy on cleaning up the electric power sector, with great success. Now, as attention turns to transportation, it’s critical that climate advocates fully understand the unique challenges and opportunities at play. Here’s hoping this framework can make a contribution to that important conversation.

[1] There are other models, most notably the “avoid-shift-improve” framework for cutting transportation carbon pollution used internationally.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

Beyond the politics of nostalgia: What the fall of the steel industry can tell us about the future of America

Let us now praise rooftop solar: A tale from New England

Automakers could have learned to build EVs. They paid Tesla to do it instead.