A New Role for Insurance Companies as Consumer Advocates

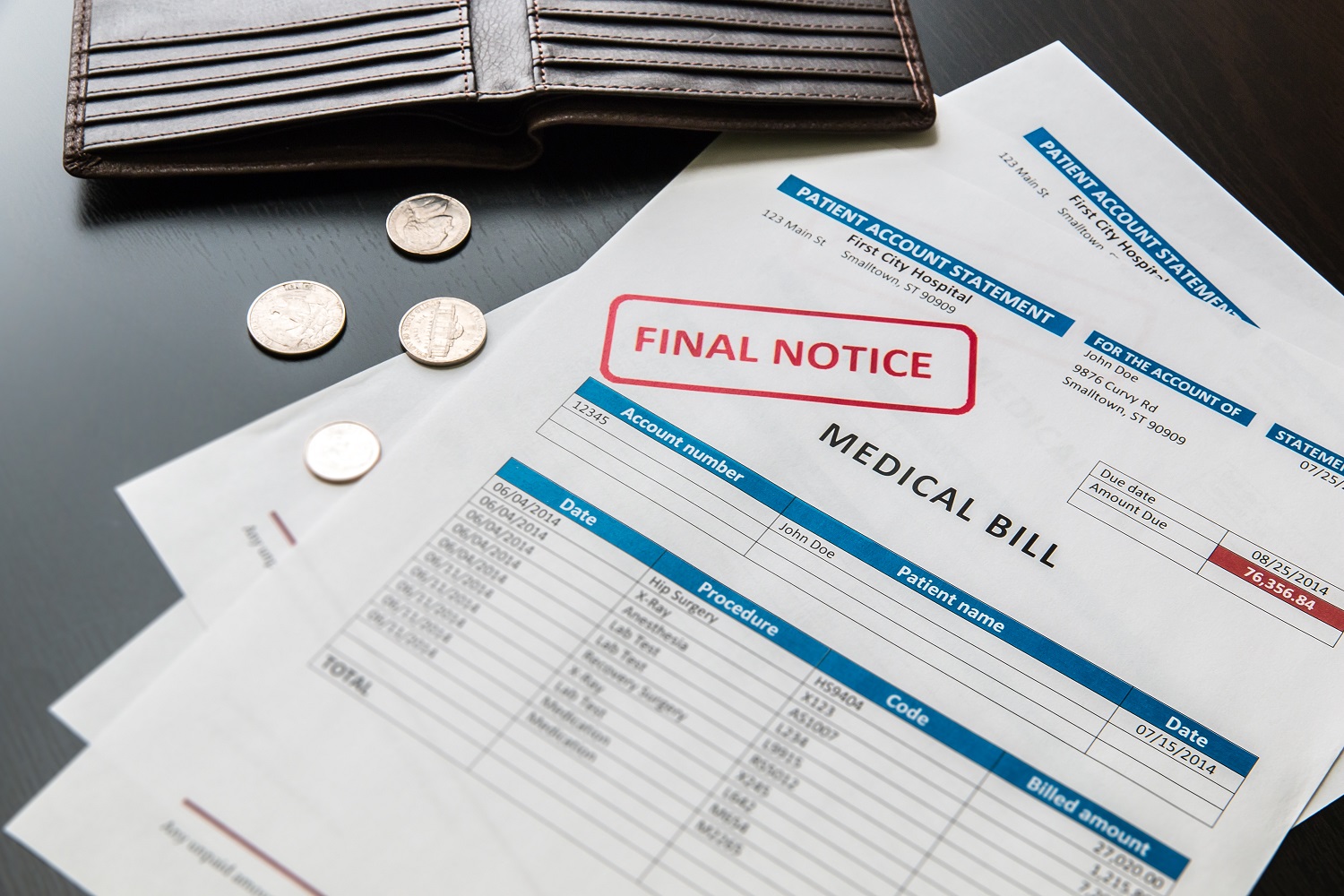

The Los Angeles Times recently ran a story highlighting yet another example of how irrationally and unpredictably expensive health care can be. What the story didn’t mention is how states might go about encouraging health insurance companies to apply more scrutiny to the bills they receive and help keep down the cost of care.

The Los Angeles Times recently ran a story highlighting yet another example of how irrationally and unpredictably expensive health care can be. What the story didn’t mention is how states might go about encouraging health insurance companies to apply more scrutiny to the bills they receive and help keep down the cost of care.

The story in the L.A. Times was of a surgery center that charged $87,500—nearly 30 times the standard charge—for an uneventful, 20-minute knee surgery. The patient’s insurance company didn’t challenge the charge and was prepared to pay nearly the entire bill, until the patient raised questions with California’s attorney general’s office. Eventually, the insurance company negotiated a lower price with the surgery center, which cut its bill by roughly $70,000.

One of the factors in the rising cost of care is that health care providers have the ability, in some cases, to charge a price that doesn’t directly reflect the cost of providing care. If it appears that the insurance company is contractually obliged to pay for out-of-network care, no matter the price, as was the case for the patient in the L.A. Times story, or if hospitals and physician associations have enough market power that they can set a higher price, then the cost of care rises. As a result, the total cost of health care—and health insurance premiums—goes up.

Part of the solution to this problem is to have insurance companies act more like advocates for their customers. If I hired a general contractor to remodel my kitchen, I’d expect him to push his subcontractors to deliver quality work at a reasonable price, not simply pay whatever they charged and then increase his bill to me. If he didn’t, I’d be asking him hard questions and pushing him to negotiate a better deal with subcontractors. I might even withhold payment.

Consumers don’t have that same ability in the health care market. Consumers who refuse to pay for insurance if the price goes too high won’t have health care coverage—a much harder choice than firing a contractor and living with a half-completed renovation. That’s why it is so important that insurance companies play a role in questioning unreasonable bills from health care providers. (Of course, health insurance is different from home construction in another important way: I might be able to tolerate second-rate home repairs but I certainly don’t want a second-rate heart surgeon performing bypass surgery. That’s why information on the quality of care from different providers needs to be widely available, and why adequate oversight is necessary to ensure insurance companies strike the right balance between watching costs and maintaining quality.)

One way to encourage insurance companies to look harder at invoices is by instituting stronger review by state regulators of insurance companies’ proposed rate hikes. By limiting the ability of insurers to pass along all cost increases to consumers, we can create an incentive for them to challenge unreasonable charges. The Affordable Care Act provides $250 million for states to help fund better reviews of rate increases. In Oregon, which has employed rate review for several years, the Insurance Division of the Department of Consumer and Business Services reviews rate increases proposed by insurers in the small-group and individual insurance market. The Insurance Division hires actuaries and a consumer organization to delve into each proposal and decide if the increase is reasonable. In the most recent one-year period for which data are available, the Insurance Division scaled back 18 of 23 rate hikes proposed by insurers, reducing rates by a total of $35.6 million in one year.

If insurance companies are less certain that they can raise rates to pay whatever price health care providers charge, they may be more likely to question those bills—and help keep down the cost of care for all of us.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

Developing the antibiotics we need

How useful are hospital price transparency tools?

More and better testing would protect us from chemical threats