Marine protected areas virtual tour: California’s MPAs

After less than two decades, America’s first science-based, statewide MPA network has shown what a strategically-planned, carefully-managed MPA system can achieve.

In the first of our series of posts exploring the experience of marine protected areas around the world, we focus on the MPAs off the coast of California – America’s first science-based, statewide MPA network.

In 2004, following the adoption of California’s 1999 Marine Life Protection Act, California began a consultation and planning process that would culminate in 2012 in the implementation of the country’s first statewide MPA network.1 Approximately 852 square miles of ocean off the California coast – a little over 16 percent of the state’s waters – were placed under the protection of 124 MPAs.2 Of this MPA area, approximately 60 percent (9 percent of state waters) is in no-take MPAs.3 Early studies have shown that these protections are already delivering substantial benefits for fish and other wildlife and habitats.4

A 2013 study of MPAs off the state’s Central Coast found a greater abundance of certain fish species, including cabezon, lingcod and black rockfish, in protected areas than in non-protected areas.5 The endangered black abalone – a species of sea snail once numbering in the millions along California’s coast but now harvested almost to extinction — increased in numbers and size inside MPAs within five years of these protections being implemented.6 Similarly, within five years of the establishment of the North Central Coast’s Sea Lion Cove State Marine Conservation Area (SMCA) – created in part to protect an important abalone nursery – populations of red abalone had experienced a “sharp increase.”7

Research has also found evidence that California’s MPAs are benefiting the ocean environment outside their boundaries. A 2015 study looking at larval dispersal within and outside MPAs found “significant spillover” into surrounding areas, indicating that the protected areas are potentially important sources of new additions to the populations of a large percentage of resident species.8 Similarly, a 2019 study revealed connectivity between populations of kelp rockfish in a number of Central Coast MPAs and in non-protected areas nearby.9

The Channel Islands MPAs

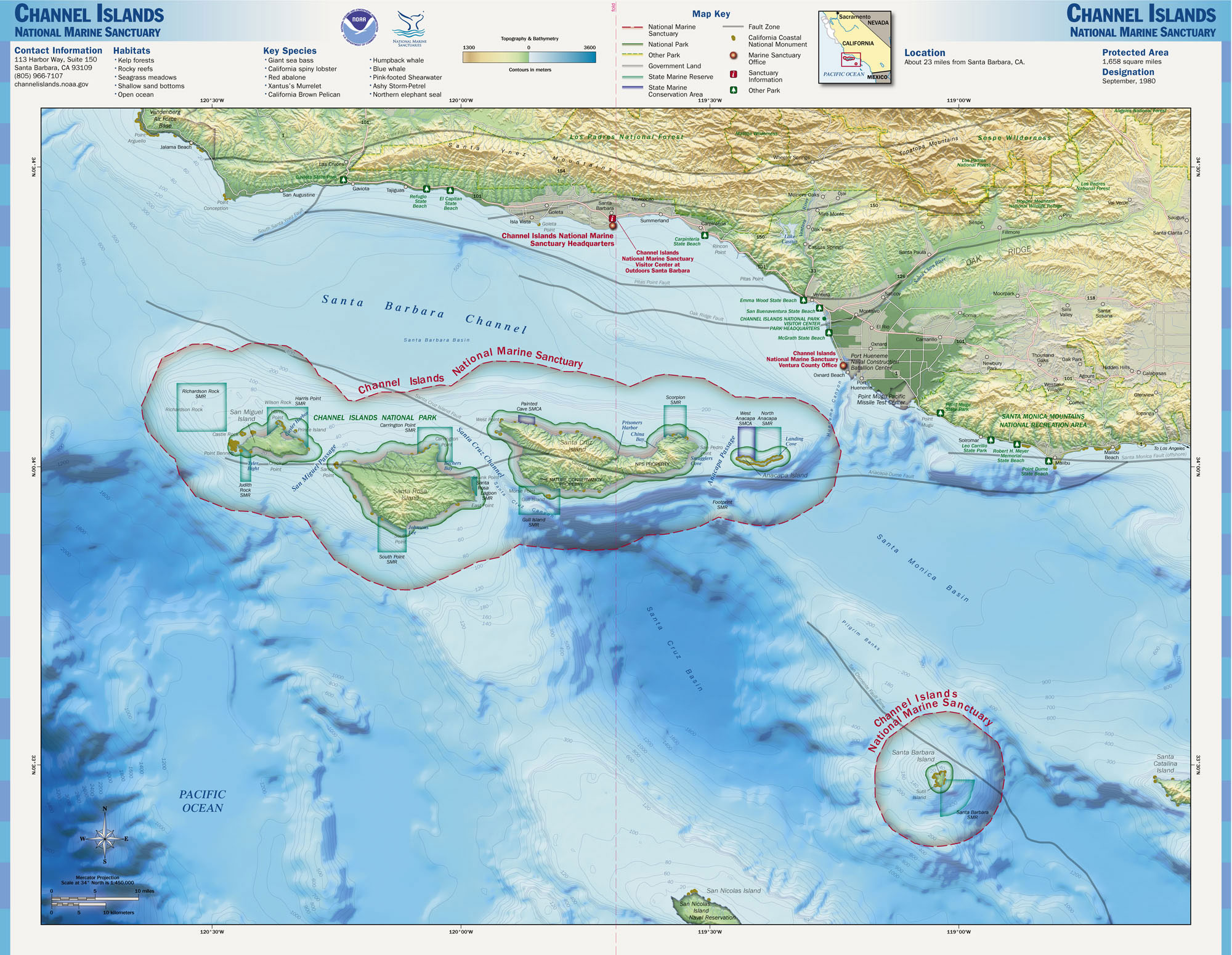

In 2003, the State of California designated 10 marine reserves and two marine conservation areas in state waters within the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary10 – a 1,470 square mile area of ocean around Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel and Santa Barbara islands in the Santa Barbara Channel off the coast of Southern California.11 In 2006 and 2007, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) extended the protections into the sanctuary’s deeper, federal waters, bringing the total number of marine reserves in the network to 11. Within these reserves, all fishing and other extractive activities are prohibited, while the two marine conservation areas allow limited take of lobster and pelagic fish.12

The Channel Islands sanctuary is the largest MPA network off the continental United States.13 Within its boundaries exist numerous endangered species and a diverse patchwork of sensitive habitats, including rocky shorelines and sandy beaches, inshore kelp forests, soft bottom habitats and rocky reefs, and deep-sea coral gardens.

Within just a few years of its designation, monitoring studies were already beginning to see the effects of the protection given to the area. A study published in 2010 found that the density of targeted (i.e., fished) fish species had increased inside the protected zones by 50 percent, and their biomass had increased by 80 percent, in the first five years of the reserves’ existence. The biomass of predators inside the reserves was “significantly greater” than in unprotected areas, with 1.8 times more piscivores (animals that primarily eat fish) and 1.3 times more carnivores in these zones.14

This is significant, since both of these groups play important roles in kelp forest ecosystems. California sheephead and spiny lobsters, for example, are important predators of sea urchins, and help prevent kelp beds – which support more diverse communities, complex food webs and healthy fish populations – from being destroyed through overgrazing by unchecked sea urchin populations.15

A 2015 study found that the average size of kelp bass and California sheephead was “significantly larger” in most of the older Northern Channel Islands marine reserves than in non-protected areas.16 The same study found that three of the five targeted invertebrate species in the Northern Channel Islands – California spiny lobster, red sea urchin and warty sea cucumber – were considerably more abundant in these protected areas.17

Protections also had a significant impact on species’ overall biomass. Between 2008 and 2013, average biomass for targeted fish species within the boundaries of the Northern Channel Islands reserves increased by 52 percent, whereas outside these MPAs it grew by just 23 percent over the same period.18 A separate study, also published in 2015, similarly found that biomass of targeted fish “increased consistently inside all MPAs in the network.”19

The success of California’s MPAs has been attributed in part to the comprehensive, stakeholder-driven planning process that preceded their implementation. This process centered around integrating regional scientific knowledge, engaging local communities, and evaluating the potential economic impacts of marine protections off the California coast. California has also been recognized for its post-implementation management strategy. Since implementing its MPA network, the state has put in place a well-resourced MPA management program steered by a statewide, multi-agency leadership team, with a focus on “scientific monitoring, interagency coordination, public education and outreach, and enforcement,”20 providing a valuable case study in how to plan, implement and manage a successful statewide network of marine protected areas.

Image credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- UC San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Early Results Suggest California Marine Protected Areas are a Success, accessed 7 July 2020, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709202552/https://scripps.ucsd.edu/news/early-results-suggest-california-marine-protected-areas-are-success.↩︎

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Regional MPA Statistics, accessed July 7 2020, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709202726/https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/MPAs/Statistics.↩︎

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Protected Areas Center, Marine Protected Areas of the United States: Conserving our Oceans One Place at a Time, n.d., archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709203735/https://nmsmarineprotectedareas.blob.core.windows.net/marineprotectedareas-prod/media/archive/pdf/fac/mpas_of_united_states_conserving_oceans_1113.pdf, 4.↩︎

- Samantha Murray et al., “A Rising Tide: California’s Ongoing Commitment to Monitoring, Managing and Enforcing its Marine Protected Areas,” Ocean & Coastal Management, 182, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104920, December 2019.↩︎

- California Ocean Science Trust et al., State of the California Central Coast: Results from Baseline Monitoring of Marine Protected Areas 2007–2012, 2013, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709204109/https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=133101&inline.↩︎

- Ibid., 3.↩︎

- California Ocean Science Trust and California Department of Fish and Wildlife and Ocean Protection Council, State of the California North Central Coast A Summary of the Marine Protected Area Monitoring Program 2010-2015, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709204815/https://og-production-open-data-cnra-892364687672.s3.amazonaws.com/resources/953d0edd-7d41-4558-9bb6-3242eb3cec93/ncc-state-of-the-region-report-nov-2015.pdf?Signature=pi6p5Wt26uUgb%2FTz23Fsbme9GGI%3D&Expires=1594331282&AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJJIENTAPKHZMIPXQ, 5.↩︎

- Alice E. Harada et al., “Monitoring Spawning Activity in a Southern California Marine Protected Area Using Molecular Identification of Fish Eggs,” PLoS ONE 10(8): e0134647, doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134647, 2015.↩︎

- Diana S. Baetscher et al., “Dispersal of a Nearshore Marine Fish Connects Marine Reserves and Adjacent Fished Areas Along an Open Coast,” Molecular Ecology, 28(7): 1-13, doi: 10.1111/mec.15044, February 2019.↩︎

- California Department of Fish and Game, Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, and Channel Islands National Park. 2008. Channel Islands Marine Protected Areas: First 5 Years of Monitoring: 2003–2008. Airamé, S. and J. Ugoretz (Eds.), p.2.↩︎

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, accessed 20 June 2020, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709224928/https://channelislands.noaa.gov/.↩︎

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary: Marine Reserves, accessed 20 June 2020, archived at https://channelislands.noaa.gov/marineres/.↩︎

- Ibid.↩︎

- Scott L. Hamilton et al., “Incorporating Biogeography into Evaluations of the Channel Islands Marine Reserve Network,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 107(43): 18272-18277, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908091107, October 2010.↩︎

- Ibid.↩︎

- Daniel J. Pondella et al., South Coast Baseline Program Final Report: Kelp and Shallow Rock Ecosystems, 2015, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20200709230401/https://caseagrant.ucsd.edu/sites/default/files/SCMPA-27-Final-Report_0.pdf, 49.↩︎

- Ibid., 59.↩︎

- Ibid., cited in Samantha Murray et al., “A Rising Tide: California’s Ongoing Commitment to Monitoring, Managing and Enforcing its Marine Protected Areas,” Ocean & Coastal Management, 182, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104920, December 2019.↩︎

- Jennifer E. Caselle et al., “Recovery Trajectories of Kelp Forest Animals are Rapid Yet Spatially Variable Across a Network of Temperate Marine Protected Areas,” Scientific Reports, 5:14102, September 2015.↩︎

- Samantha Murray et al., “A Rising Tide: California’s Ongoing Commitment to Monitoring, Managing and Enforcing its Marine Protected Areas,” Ocean & Coastal Management, 182, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104920, December 2019.↩︎

Topics

Authors

James Horrox

Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

James Horrox is a policy analyst at Frontier Group, based in Los Angeles. He holds a BA and PhD in politics and has taught at Manchester University, the University of Salford and the Open University in his native UK. He has worked as a freelance academic editor for more than a decade, and before joining Frontier Group in 2019 he spent two years as a prospect researcher in the Public Interest Network's LA office. His writing has been published in various media outlets, books, journals and reference works.

Find Out More

Marine protected areas are the best hope for the ocean – but only if the protections are real

Marine protected areas virtual tour: Edmonds Underwater Park, WA

Marine protected areas virtual tour: Cabo Pulmo, Mexico