The high cost of medical care leaves consumers vulnerable

Fifteen years ago, I broke my leg. I wore a cast for nine months, unable to walk, drive or, in the early months, even stand for very long. Though the experience of the broken leg was awful, thankfully it didn’t break me financially. But for too many people, a health problem like this can bring financial ruin.

Fifteen years ago, I broke my leg. It was no small injury. I had surgery to screw my leg back together and then spent several days in the hospital. In the subsequent months, my bones grew at a snail’s pace and the skin over the injury looked like it wouldn’t heal, leading to innumerable doctor visits. I wore a cast for nine months, unable to walk, drive or, in the early months, even stand for very long.

Though the experience of the broken leg was awful, thankfully it didn’t break me financially. But for too many people, a health problem like this can bring financial ruin.

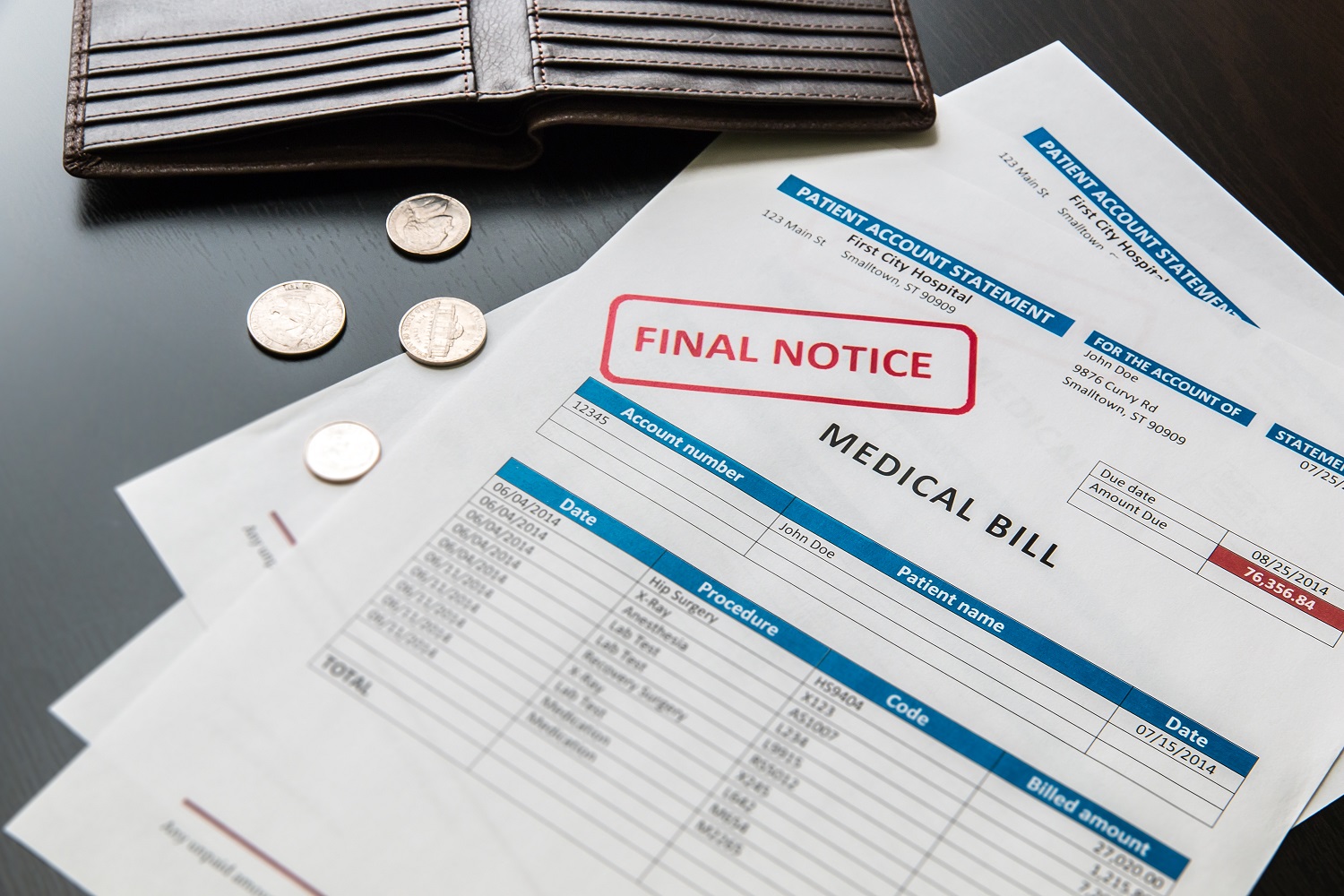

When the first statements from the insurance company arrived, showing that the hospital would have charged me $40,000 if I hadn’t had insurance, my husband said “if we didn’t have decent insurance, we would lose the house because of this.” According to later insurance statements, the providers, pharmacies and medical device manufacturers I used in the months after my hospital stay would have expected an uninsured patient to pay another $20,000 for care, medicine and devices. Because I had good coverage (and was able to continue earning an income by working from home), the medical charges didn’t destroy our household finances.

However, too often that’s not the case for sick or injured patients. In a recent analysis with OSPIRG, we found that 60% of consumers who filed for bankruptcy in Oregon in 2019 reported having medical debt. For those with medical debt, the median amount they owed for health care expenses was $2,326, but 15% reported that they owed more than $10,000 to various providers. We don’t know if it was the medical debt that triggered these bankruptcy filings, but it had to have been a contributing factor for many.

Most of these bankruptcy filers probably had health insurance – 94% of Oregonians do. Many earned solid incomes: Even the majority of bankruptcy filers earning $70,000, $80,000 or $90,000 annually reported having medical debt.

The problem, as we explain in our report, Unhealthy Debt, is that health care overall – not just how much consumers have to pay – is dreadfully expensive. This means insurance is extremely expensive as well. Paying for insurance can strain household budgets, leaving consumers on shakier financial ground if they face an unexpected expense, medical or otherwise. Insurance often is also inadequate, requiring patients to pay thousands of dollars toward their care before insurance begins to pay.

Patients don’t choose to incur huge medical expenses, and it isn’t their preference to leave medical bills unpaid. Nobody chooses to break a leg, get diagnosed with cancer, or have an injury that requires stitches in an emergency room. Survey data nationally shows that patients who struggle to pay medical bills often will use up most or all of their savings, borrow money, get another mortgage, or take on large amounts of credit card debt in an attempt to pay off their medical debt.

The solution to this problem isn’t to ask patients to choose their health care or insurance provider more carefully, or to spend more wisely. It is to address the high cost of health care. Policies that protect consumers, such as banning surprise medical bills, are good, but we also need to lower the overall cost of care. That includes setting limits on how much providers and insurers can increase prices each year, adopting a public option health plan with price limits, and ending consolidation between providers that drives up the cost of care, among other policies.

Medical problems are stressful enough, for both patients and their families, without the threat of financial ruin. Lowering the cost of health care will help.

Photo: volgariver via DepositPhotos

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Find Out More

Developing the antibiotics we need

How useful are hospital price transparency tools?

More and better testing would protect us from chemical threats