Half the People in these Neighborhoods Walk to Work. What Can We Learn from That?

If you want to have a city where lots of people walk to work, there are a few things you can do: Build neighborhoods with lots of room for people and little for cars. Make them beautiful and interesting. Put them as close as possible to a lot of jobs. And invest in transportation modes that can deliver workers to those jobs from around the metropolitan area without shredding the fabric of your city.

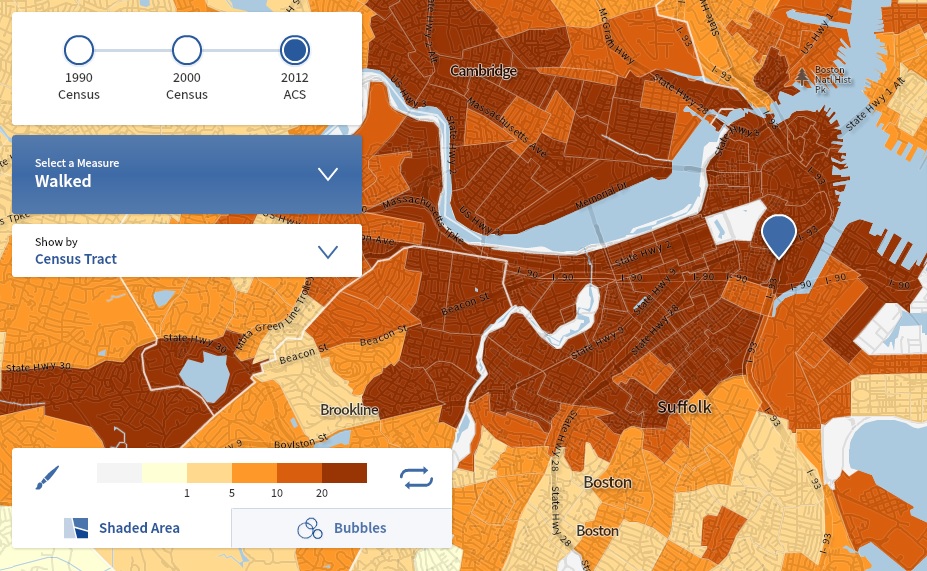

Last week, the U.S. Census Bureau came out with a new mapping tool that enables users to see how people commuted to work in 1990, 2000 and 2012, all the way down to the tract level.

I was particularly struck by the map below, showing the share of commuters in various Boston neighborhoods who walk to work.

Boston is the nation’s number one walk-to-work city, with 15 percent of all Bostonians getting to work on foot.[1] Many areas of the city do much better. The dark brown areas on this map are places where more than 20 percent of all commuters walk, but in several of these Census tracts – particularly in the Back Bay, Fenway, North End and Beacon Hill – more than half of all commuters walk to work.

Those communities are some of the most desirable in Boston and they’re densely populated – we’re talking thousands of people who, in most other American cities, would be in their cars, creating pollution and congestion. What is it about these neighborhoods that enables walking to remain such a central mode of transportation? And, more importantly, is there anything we can learn from them?

Here are a few thoughts:

Land use matters.

If you want people to walk a lot, building a 19th century neighborhood and not messing with it too much is a good way to start. The Back Bay, for example, is packed with three- and four-story brownstones. There are virtually no surface parking lots. The few nearby parking spaces go for insane prices. Many of the streets are residential in character – almost shockingly so for the center of a major American city – but it is mixed-use enough that you can take care of most of your needs on foot. Back Bay has a Walk Score of 97 and still ranks as only the sixth most-walkable Boston neighborhood, with the far less tony (but rapidly gentrifying) North End and Chinatown heading the list. In most of America, building a neighborhood like this would be not only unthinkable, but also illegal, due to off-street parking requirements and the like. Even in Boston, we’re not building new neighborhoods quite like it. Perhaps we should be.

Not just walkable, walkalicious.

“Walkability” is the real estate buzzword du jour, but I wonder if it might be setting the bar too low. Walking in neighborhoods like the Back Bay and North End isn’t just possible, it’s desirable – so much so that tourists pay good money to come here from around the country to do it. The various close-in neighborhoods of Boston each have their own unique mix of streetlife, storefronts, and cool architectural and historical details, all best appreciated at walking speed and scale.

Aesthetic qualities like these actually matter from a transportation policy point of view. Transportation engineers and economists have historically considered time spent in transportation as something to be minimized (in econ wonk-speak, transportation is a “derived demand”). In general, they believe, people will choose the fastest, cheapest way to get from Point A to Point B. Over the last decade, however, scholars have begun to question that assumption (PDF), finding that many travelers value travel for its own sake.

Here’s a personal, if trivial, example: If I am headed from my office downtown to a night game at Fenway Park, I will almost always take the extra 20 minutes to walk down Beacon Street or Commonwealth Avenue through the Back Bay as opposed to hopping on the T. The walk is lovely, while the Green Line on the evening of a Sox game is anything but. If we want to encourage people to walk – or to take transit, for that matter – small investments that make those trips more enjoyable and comfortable could pay big dividends. Remember this the next time the all-highways-all-the-time crowd targets federal funding for pedestrian and bicycling infrastructure for the chopping block, as they seem to do every time transportation funding gets tight.

The roads not taken.

Boston was the site of one of the first successful “highway revolts,” the fight against the completion of the Inner Belt highway. That highway and others would have sliced Cambridge, the Back Bay, the South End and other walkable and bikeable neighborhoods to ribbons. Even if those neighborhoods could have maintained their integrity, the highways would have made it more difficult to cross from one neighborhood to another– a problem similar to the isolation the North End experienced from the rest of Boston prior to the burial of the Central Artery during the Big Dig. The decision to build or not build, or expand or not expand a highway can have major, long-lasting implications for the functioning of neighborhoods, as many cities have learned to their chagrin.

Have lots of jobs nearby

The Back Bay, the North End and other Boston neighborhoods could not be walk-to-work bastions if there weren’t lots of jobs nearby. In the 1960s, Boston committed itself to dense, skyscraper development along the “High Spine” – an axis that stretches from the city’s Financial District downtown through the Back Bay. The employment density of the High Spine would have been impossible to support without an efficient metropolitan transportation network, one that got a big boost from a series of extensions and improvements of the regional transit system in the 1980s and 1990s. The point of the High Spine was to increase density in a targeted area while allowing other Boston neighborhoods to retain their traditional character. Not only did it work, but as a side benefit it brought tens of thousands of jobs to within walking distance of those same traditional neighborhoods. The city of Boston has added more than 100,000 jobs since 1970, many of them easily within walking distance of these and other neighborhoods. And the share of Boston residents driving to work alone has dropped from 40 percent in 1990 to less than 37 percent in 2012.

So if you want to have a city where lots of people walk to work, there are a few things you can do: Build neighborhoods with lots of room for people and little for cars. Make them beautiful and interesting. Put them as close as possible to a lot of jobs. And invest in transportation modes that can deliver workers to those jobs from around the metropolitan area without shredding the fabric of your city.

Will taking all those steps magically get half of your neighborhood’s residents to walk to work? Maybe not. But it is amazing how rarely those steps are really attempted these days, even here in “America’s Walking City.”

[1] Interestingly, more than a quarter (27 percent) of Boston 16 to 24 year-olds walk to work – a number significantly higher than the number who drive alone. That’s compared to 7 percent of 16 to 24-year-olds who walk to work nationwide.

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.