Edward Abbey and the robber baron mindset

Decades after he first issued them, Edward Abbey’s calls for the defense of America’s wilderness still feel uncomfortably relevant. As much as Abbey's work emphasizes the importance of legal protections against those who would plunder America’s natural lands, however, it also – more importantly – invites us to consider the value system that underlies, excuses and legitimizes this vandalism.

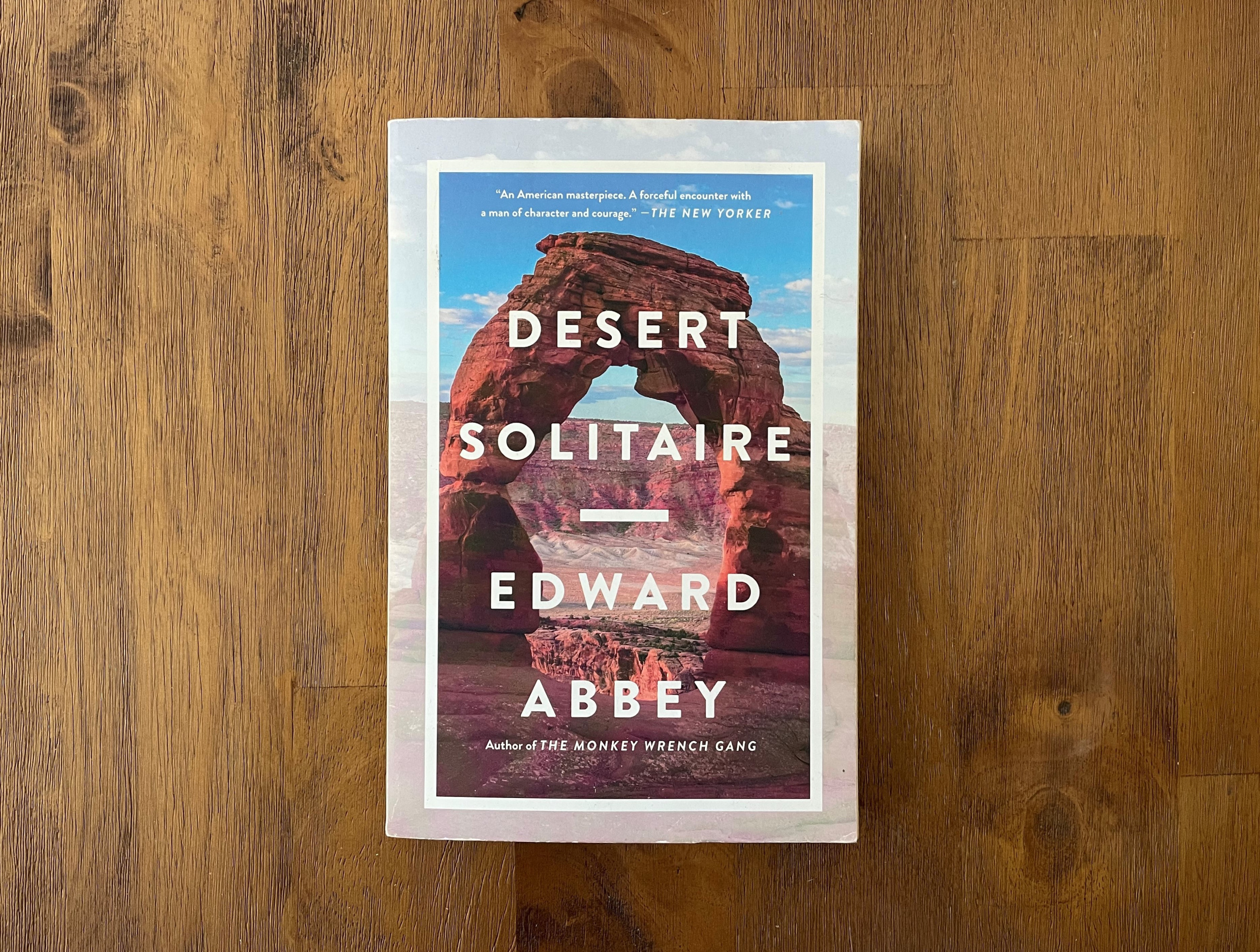

When Edward Abbey’s “Desert Solitaire” was first published in 1968, it didn’t immediately find much of a readership. “Another book dropped down the bottomless well. Into oblivion,” wrote a despondent Abbey in his journal shortly after its release. History of course had other plans for what would soon come to be considered a classic of American nature writing, one of the seminal works of its generation to illuminate what’s at stake should industrial civilization be allowed to continue on its rampage through the natural world.

“Desert Solitaire” was one of several books published during the 1960s that helped embed that latter understanding in the American collective consciousness. Detailing Abbey’s experiences during two summers as a National Park Service ranger at Arches National Monument, it is at once a timeless paean to the stark beauty of the desert wilderness and an impassioned plea for the protection of this landscape from the “sweating scramble for profit and domination.”

In those days, Arches was largely undeveloped, tourists were comparatively few, and Abbey was left to pursue his literary and philosophical endeavors largely undisturbed. But the future he foresaw for the wild lands of the American desert nonetheless led him to believe that what he was writing was “not a travel guide but an elegy.” Even in his most pessimistic contemplations on modern humanity, however, it is difficult to imagine that Abbey could have predicted a future so bleak that it would include a Starbucks at the base of Yosemite Falls, much less the industrial-scale demolition of sacred Native American burial grounds with high explosives.

Half a century after its publication, Abbey’s polemic against those who would despoil the landscapes he wrote about with such affection began to feel tragically contemporary once again, as America looked on in horror while its government embarked on an assault on the nation’s public lands on a scale that Abbey could never even have imagined.

At the behest of the fossil fuel industry, whose lobbyists now staffed the very institutions charged with protecting America’s public lands, the Trump administration orchestrated the largest reduction of protected land in U.S. history. By the time Trump left office, his doctrine of “energy dominance” had led to the removal of protections for more than 35 million acres of public lands, and huge swathes of the nation’s forests, wildlife refuges, national parks and monuments offered up for mining and development, including the largest single rollback of land protections to date in the form of the 2 million-acre land grab that opened up Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments to oil and gas drilling, uranium mining and commercial cattle grazing.

As much as Abbey’s work underlines the critical importance of legal protections against those seeking to plunder America’s natural lands in pursuit of profit, it also – perhaps more importantly – invites us to consider the value system that underlies and legitimizes this vandalism. The industrialization of the natural world is not something that just happens. Nor is it the unique preserve of those who “frankly and boldly advocate the eradication of the last remnants of wilderness and the complete subjugation of nature to the requirements of […] industry.” Rather, it is a symptom of a particular mindset, a social paradigm built around the doctrine of expansion at all costs – development for the sake of development, growth for the sake of growth: “the ideology of the cancer cell.”

This paradigm of course exists in degrees, being more of a guiding force for some administrations than for others, but when push comes to shove, as long as a belief in economic growth as an intrinsic good remains the dominant way of thinking, economic growth will remain the yardstick against which the success of any government is measured.

“Desert Solitaire” is a searing indictment of this worldview – a worldview that, apart from anything else, simply makes no sense in an age of material abundance, where we have at our disposal all the tools we need to satisfy our energy demands without having to mine and drill and otherwise destroy “this natural paradise which lies all around us.” Not only does this paradigm, and the legitimation of indifference to nature it engenders, have dire environmental consequences, it rebounds on us as human beings in profound ways. “An economic system which can only expand or expire must be false to all that is human” Abbey writes. “A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying the principle of civilization itself.”

“Desert Solitaire” came into the world against the backdrop of growing public awareness of the damage inflicted on the natural world by decades of exploitation. The legal protections instituted as a result have since been a crucial last line of defense against such behavior, but we know now just how easy it is for an administration so inclined to systematically dismantle, circumvent or just straight-up ignore those protections. Even the most well-intentioned approach to natural lands will always have to compete with other, economic considerations – and there is never any guarantee that it will win.

In short, if there is a lesson in the work of Edward Abbey – America’s original vox clamantis in deserto – it is that it’s simply not enough to “throw the bums out.” As long as the pursuit of economic growth remains the dominant paradigm, somewhere down the line they’ll likely just be replaced by a different set of bums – more benign in their rhetoric perhaps, and less destructive in their actions, but nevertheless guided and constrained by the same underlying ideology. So, while opposing the individual actions that green-light the plunder of the natural world, it is also incumbent upon us to take a long, hard look at the worldview that underlies, excuses and legitimizes those actions, and to ask ourselves whether that worldview is leading us to a place we really want to be.

Image: James Horrox

Topics

Authors

James Horrox

Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

James Horrox is a policy analyst at Frontier Group, based in Los Angeles. He holds a BA and PhD in politics and has taught at Manchester University, the University of Salford and the Open University in his native UK. He has worked as a freelance academic editor for more than a decade, and before joining Frontier Group in 2019 he spent two years as a prospect researcher in the Public Interest Network's LA office. His writing has been published in various media outlets, books, journals and reference works.

Find Out More

Rewilding: The promise of a hands off approach to conservation

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

Nature’s little helpers: The semiaquatic heroes you didn’t know you needed