Cutting Corners at a Cost: When Saving Money on Infrastructure Puts Health at Risk

After 20 years in Columbia, Maryland, my partner's mom recently accepted a job offer in Jackson, Mississippi, and made the move. When she got there, however, there was one thing she didn’t expect: the water in Jackson violates safe drinking standards.

Later this month, I will be visiting my partner’s mom in her new home of Jackson, Mississippi. After 20 years in Columbia, Maryland, she accepted a job offer in Jackson and made the move. Her reviews have been mostly what you expect: people tease her for her accent, she enjoys the warmer weather, it’s hard to find good pizza.

There was one thing she didn’t expect, however: the water in Jackson violates safe drinking standards.

Lack of access to clean drinking water is a pressing problem all over the world. Many places in developing countries simply don’t have the resources to provide safe drinking water to all their people.

That’s not the case in the United States, one of the richest nations in the world. Yet, from Jackson to Flint, we repeatedly fail to make the investments in infrastructure that can deliver safe water to everyone – even when making those investments saves money in the long run.

The current water issue in Jackson, Mississippi can trace its roots back three years. In January 2016, the city alerted residents that elevated levels of lead – similar to those that triggered the crisis in Flint, Michigan – had been discovered in the water six months earlier. To address the problem, the city opted to alter their water treatment process by using soda ash instead of lime.

Two and a half years later, Jackson residents got another surprise when, in June 2018, the Mississippi Department of Health announced that Jackson was in violation of safe drinking water standards once again. For the previous six months, the city failed to meet pH minimums at their water treatment plant, as well as at the city’s water distribution center.

Despite the fact that acidic water can cause lead to leach from pipes, the city has told residents that they are not at elevated risk of lead exposure. The city’s drinking water advisory, however, sends a different message. The city has warned children under five years old and pregnant women not to drink the water and everyone to let water run for 1-3 minutes before cooking with it. The city has also suggested that residents clean their faucet aerator frequently and ensure that children have adequate lead testing done.

Regardless of any health risks faced by Jackson residents, the costs of the city’s drinking water restrictions are adding up. If you assume that every child under five in Jackson has been drinking bottled water instead of water from the tap, the cost to those families for six months of bottled water would be on the order of about $1.9 million.[1]

The same water from the tap would have cost under $6,000. Moreover, the equipment needed to prevent the problem from arising in the first place would have cost $500,000. The city had cut that piece of equipment from the budget before the problem emerged.

The decision to omit that equipment might have saved the city $500,000, but it cost residents a net of almost $1.4 million and put their health at risk.

This is an example of a government being reactive rather than preventative, and Jackson is not the only place where it happens. Critical equipment is fixed after it stops working, not maintained so it doesn’t break in the first place. Chances are taken with public health in order to save a few dollars in the short run. Leaders seeking to avoid difficult problems place unfounded hope that we will be able to adapt to the consequences rather than making sure that point is never reached.

Jackson may be culturally different from Columbia. The pizza may be worse and the sweet tea better. But when it comes to exercising foresight to take care of the critical infrastructure that protects our health and environment, it’s no different than many other places around the United States. And we all have a role to play in fixing it.

[1] According to 2017 population estimates based off census data, there are 12,188 children under the age of five in Jackson. Excluding newborns and assuming an even age divide among children, there are roughly 9,750 children between the ages of 1-4 in affected by the water situation in the city. Children that age are supposed to drink 44 ounces of water a day. A standard water bottle has 17 ounces and costs about $0.42. That means that a child would need about 2.6 water bottles a day. At a cost of $1.08 a day for the six months the city has been in violation, each child would need $194.40 of bottled water thus far. That would mean that the residents of Jackson, Mississippi would have spent $1,895,400.00 on water bottles for their children.

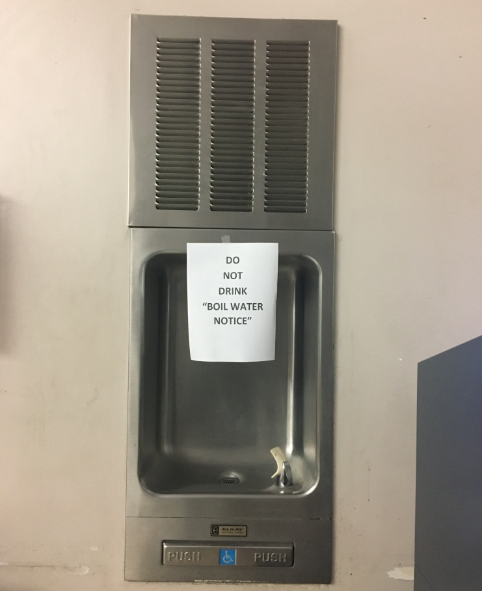

Image: A drinking fountain in a Jackson post office.

Topics

Authors

Find Out More

From gray to green: How (and why) to depave

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

More and better testing would protect us from chemical threats