Emily Schneider

Intern

To encourage patients to purchase their name-brand drugs instead of generic versions, pharmaceutical companies sometimes offer coupons that reduce the patient’s copayment for the brand-name drug below the copayment for the generic drug. Patients choose the cheaper option for them – the name-brand drug – and the pharmaceutical company makes a sale. The problem, however, is that the patient’s insurance company ends up paying far more for the name-brand drug than it would have for a generic substitute. The result is that the total cost – the combined amount paid by the patient, covered by the coupon and paid by the insurance company – of filling the patient’s prescription is significantly higher, and the cost to the insurance company increases significantly.

Intern

Frontier Group intern Emily Schneider is a third-year student at Dartmouth College, where she studies biology and public policy.

When most Americans fill a prescription, they share the cost of the drug with their insurance company, usually only paying a small fraction of the cost in the form of a copayment. The insurance company pays the rest and covers this outlay by collecting premiums.

To contain costs and keep premiums low, insurers will often require higher copayments from patients for expensive or name-brand drugs and lower copayments for cheaper generic drugs.

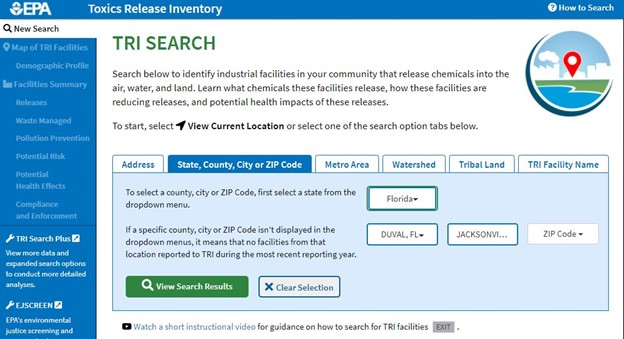

Generic drugs are often cheaper for patients and insurers. (Source: Grande, 2012).

Without a coupon, both the patient and the insurer pay less if the patient chooses the generic drug. Simvastatin is a generic alternative to Lipitor. Both drugs are used to treat high levels of cholesterol.

Generic drugs are considered to be medically equivalent to their name-brand counterparts, are significantly cheaper, and help to control spending on prescription drugs and healthcare costs overall. From 2007 to 2016, the use of generic drugs saved $1.67 trillion in healthcare spending without reducing the quality of care that patients received.

Pharmaceutical companies, however, dislike generic drugs because they reduce sales of name-brand drugs. To encourage patients to purchase their name-brand drugs instead of generic versions, pharmaceutical companies sometimes offer coupons that reduce the patient’s copayment for the brand-name drug below the copayment for the generic drug. Patients choose the cheaper option for them – the name-brand drug – and the pharmaceutical company makes a sale.

The problem, however, is that the patient’s insurance company ends up paying far more for the name-brand drug than it would have for a generic substitute. The result is that the total cost – the combined amount paid by the patient, covered by the coupon and paid by the insurance company – of filling the patient’s prescription is significantly higher, and the cost to the insurance company increases significantly.

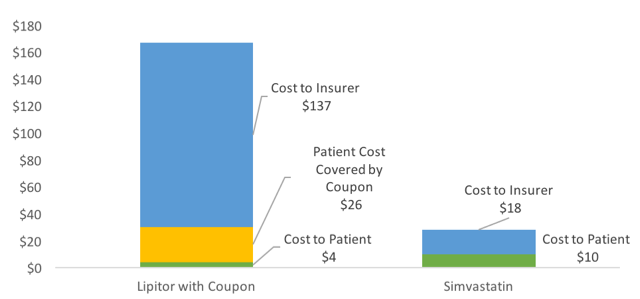

Coupons make name-brand drugs cheap for patients but expensive for insurers. (Source: Grande, 2012).

With a coupon, the patient pays less if they choose the name brand drug, while the insurer pays more.

Why should consumers who get a break on drug costs care if their insurers pay more? Increased costs to insurance companies caused by these coupons are ultimately passed on to all patients in the form of higher premiums and larger deductibles to allow the insurance company to pay for their higher costs. These rate increases are applied to every patient covered, not just those who use copay coupons.

U.S. spending on pharmaceuticals and all forms of health care is out of control, in part because of misplaced incentives that lead consumers and others to make health care choices that cost more without any benefit for improved health. Copayments are an important mechanism insurers use to enlist patients in controlling health care spending. Copayment coupons effectively override this price signaling, making a more expensive drug appear cheaper to the patient and leading patients to prefer the name-brand drug that requires the insurance company to spend more.

The financial impact on insurers is compounded because patients using copayment coupons reach their out-of-pocket maximums earlier than they would otherwise. Insurance companies cannot tell when patients use coupons – they just know the pharmacy collected the full copayment for a brand-name drug, and count that towards the patient’s annual out-of-pocket maximum. Patients reach their annual maximum sooner, leaving the insurance company on the hook to cover all of their care for the rest of the year.

These coupons cause a moral hazard problem that the current insurance system is ill-equipped to deal with. They exploit fragmented incentives and distort price signals, pushing patients to make choices that increase costs and do not deliver any improvement in health or quality of life. Insurance companies are unable to directly combat this issue through raising copayments, as coupon coverage would simply increase as well. Policymakers and insurance companies have pursued other strategies to limit the use of coupons that raise overall health care costs, but these efforts have been limited in their use and efficacy.

Federal insurance programs prohibit the use of prescription coupons and designate these coupons as illegal kickbacks that work against price control measures, as patients are essentially being paid to select more expensive drugs. However, it is nearly impossible to tell if coupons are being used at the register, and an estimated 6 percent of Medicare recipients still used these coupons as of 2012. The inability to enforce bans makes regulation difficult, and campaigns by pharmaceutical companies that portray copay coupons as a way to get patients the care they need make the topic politically difficult.

The state of Massachusetts banned all use of copay coupons from 1988 to 2012. During that time, patients in Massachusetts chose generic drugs more often than did patients in New Hampshire or Rhode Island, which led to substantial savings. The ban was amended in 2012 to allow the use of coupons for drugs without an exact generic equivalent due to concerns that patients were unable to afford the most effective drugs. Researchers estimated that this action will cost plan sponsors $750 million in increased prescription drug expenses by 2022. No other states have banned copay coupons, though a bill has been sent to Governor Brown in California that would ban the coupons.

Coupons for prescription drugs drive up overall healthcare costs, often with little or no health benefit for patients. These coupons ultimately lead to billions of unnecessary dollars being spent on drugs with exact generic equivalents available for a fraction of the cost, and are one factor driving up health care costs across the board. Restricting the use of these coupons for drugs with generic equivalents would effectively reduce healthcare costs without reducing overall quality of care.

Update: California Assembly Bill No. 625 was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown on October 9, 2017, banning copay coupons in the state.

Intern